Here’s a piece to celebrate the announced discovery of the oldest intact shipwreck, a 2,400-year-old Greek ship discovered in the Black Sea with its mast, rudder, and even a rower’s bench still in place. This can’t be fully romanced into being Ulysses’ ship—it’s centuries newer—but it does give us an object, beyond the stories, to remind us of ancient sea voyages.

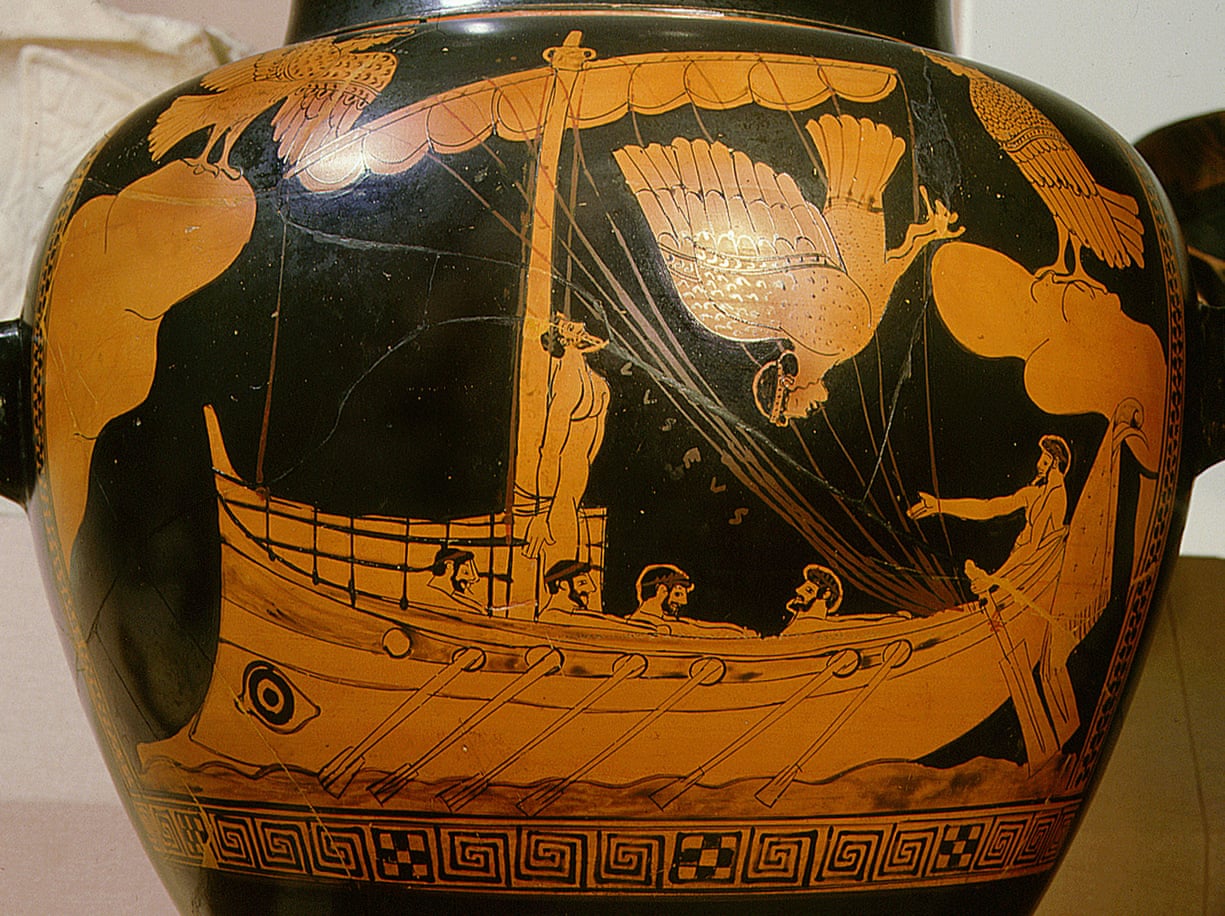

“Tales of brave Ulysses, how his naked ears were tortured by the sirens sweetly singing.” This vase depicts a ship like the one in the shipwreck.

Tennyson’s Ulysses is one of his best-known shorter works, and one I was a bit surprised to find still survives on the seabed of modern teaching syllabuses. I expect that many will read “Ulysses” as a complement to Tennyson’s American contemporary Longfellow’s “Morituri Salutamus” which we’ve featured here, as a pledge from one who is old and past their expected prime to continue to strive. After all, the most quoted section, the one I used, starts right off declaring “You and I are old.”

Well for someone my age or Dave’s—that is to say, old—this understanding might seem natural.* Indeed, as we recorded this last week, we too were not “that strength which in the old days.” But if one looks at Tennyson’s “Ulysses,” both biographically and mythologically, there are some surprises to be found.

Would you be surprised to learn, as I was, that this was not some later work by a long-lived poet (as Longfellow’s “Morituri Salutamus” was), but instead the work of a 25-year-old? Odd that in our modern times, where we often expect authenticity in our poets, were the poem is expected to be biographically true to the author’s own experience. But of course, it isn’t rare for younger people to feel old and to feel an age is past. Tennyson chose to make his poem’s speaker aged because it did represent something he felt after the death of his close friend Arthur Hallam (the same friend that his book-length epic elegy “In Memoriam A. H. H.” was dedicated to).

If one looks at the poem and sets aside preconceptions, you may find, even in its oft-quoted concluding exhortations I used, an undercurrent from this inspiration. Not only is this Ulysses a hero well-past the age of his greatest physical vigor, he’s demonstrating in his concluding speech two other characteristics. He’s looking backward to look forward. He recalls his Homeric feats, acts that in that story literally had heroes that “Strove with Gods.” He reminds his crew, in effect, “Look, we are the generation that knew Achilles personally, not the modern folk who only read about him.” Which brings us to the subject of his crew, the men he’s addressing in this exhortation. Homer’s Odyssey is clear on what happens to them, after deadly battle followed by deadly mistakes: they were all killed, long before this poem begins. Like Tennyson after the death of his friend, those who know, those who shared and could testify to Ulysses soul, are gone. So, when he asks to set sail in that boat, there will be no rowing soldiers on those benches sitting well in order, except in his soul.

So, he’s crazy? Deluded? After all, he’s plainly talking to those that aren’t there. Well this is a poem, a work of art. Ulysses might never have existed, or might not have existed in the way we know him if not for Homer, who also might not have existed. And Tennyson and his friend Hallam? We can pretty well know they existed, even if anyone who could say of the eventually long-lived Tennyson “who we knew” is now dead, and so closely equal to the imagined. This is a poem about the hereness of the not-here.

I was telling my son the other day, “Death is the leading cure for immortality,” but sometimes the cure doesn’t take. I can’t say that the LYL Band’s performance of this part of “Ulysses” is immortal, but we do strive to seek to find and not to yield. Hear it here:

Did you not see a player gadget above? Some ways of reading this blog won’t show it, so here’s a highlighted hyperlink that will also play the piece.

.

*An example of the waterworks potential for this poem when read by Helen Mirren, making Stephen Colbert cry.