I’ve done a number of William Butler Yeats poems here over the years as part of this project. We might agree that occurred because his words on the page just demand to be sounded. But there’s another side to Yeats that attracts too. He can write about political subjects with that same lyrical voice.*

One potential problem with political poetry is that a poet may not share the reader’s political stance, and while Yeats later dalliance with Fascism seems less ardent than Ezra Pound’s stronger convictions, the excellence of a poet’s lyrical gifts can’t save all examples.

Where Yeats succeeds in his political poetry, it’s often when he’s expressing complex moments of political disappointment or even disaster. This is properly the lyric poet’s area: the form where poetry isn’t about ideas but the experience of ideas. When Yeats does this the details that led to these moments are sometimes sketched in, but the poem can succeed even if one knows nothing about them.**

After all, every person with a cause eventually knows days when the cause seems damaged, perverted or defeated.

Today’s Yeats poem is a case in point. In my parochial ignorance I knew nothing about the events of the Irish Civil War of 1922. Reading a bit about it could add some more resonance to the harrowing tale Yeats tells in this poem taken from a short sequence of poems he wrote that year about the conflict, but I don’t think the reader needs to know those details for the poem to be powerful.

The poem has a central image, referred to in a refrain at the end of each stanza: honey bees and starlings*** are both nesting in the deteriorating brickwork of the place Yeats is staying in Ireland during this civil war, symbolizing those Irish factions fighting. Yeats seems to stand with the honey bees, which I read as the industrious, pragmatic, and fruitful symbol. The starlings are only raising their own brood in the same wall crevices, but from what I understand the starlings of the British Isles are somewhat of a nuisance bird, lacking in beauty and melodious song.**** Note too the detail that the starlings are being fed “grubs and flies.” Maybe the starlings aren’t evil, but what they’ve been given to subsist and grow on isn’t portrayed as lovely, a thought echoed in the final stanza.

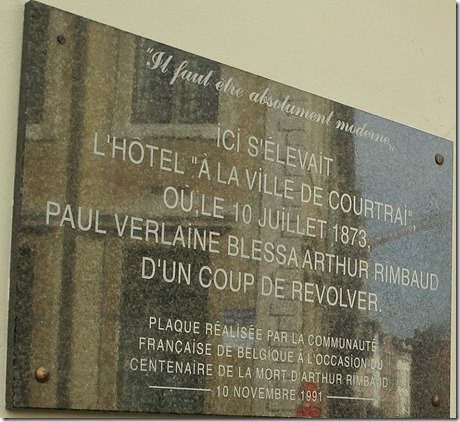

Not quite an ivory tower. Yeats had bought this old castle tower in disrepair. This page says they are still trying to repair it.

.

So, written in the sorrow of a civil war in his freshly independent country, Yeats’ plea is for a time when the chippering and tweeting loudmouths will eventually give way to those who may one day make his country prosper, though they will do so building in a country that has been emptied and hollowed out by the current disaster. That’s not a political platform, but it is an experience that you and I may resonate with now.

Musically I didn’t stint on the discordant effects this time. Despite spending a few days with this one, it may take more time and listens for me to decide if I did right by Yeats with it. The full text of the poem is here if you’d like to read along, and the player gadget to hear my music and performance is just below. If you don’t see that gadget, here’s another way to hear my performance, this highlighted hyperlink will also play it.

.

*Although Yeats wrote about a variety of subjects, it’s easy to find him fitting into the same bag as other poets seeking to reform their culture out from under colonialism. In that effort he may be more of a cultural nationalist than a functioning politician (despite his eventual term in the Irish legislature), but this concern was central to his art.

**That said, one of the most popular posts here over the years has been this one about the exact issue and persons behind the Yeats poem “To a Friend Whose Work Has Come to Nothing.”

***Yeats chose to use an archaic name for the common starling: “stare.” Yeats claimed the name was still in use in Western Ireland, but it still seems to be a deliberate choice . Stare does give him more rhyming words, but I also wonder if Yeats was thinking of punning undercurrents of stare as in looking—looking as in out his Irish window at his vision for a new independent Ireland; and “stair” as in a climb toward a higher, more perfect purpose than centuries of colonial exploitation followed by civil war. Or even “state.”

****Despite the bird’s little-liked vocalizations, starlings can learn and repeat other sounds in their environment. The best story I came upon in looking for information on why Yeats might have chosen the starling for his poem was the tale of the composer Mozart’s pet starling who could sing Mozartian passages. The starling’s discontinuous song has also been posited as an inspiration for Mozart’s famously odd-ball “A Musical Joke” (K. 522)