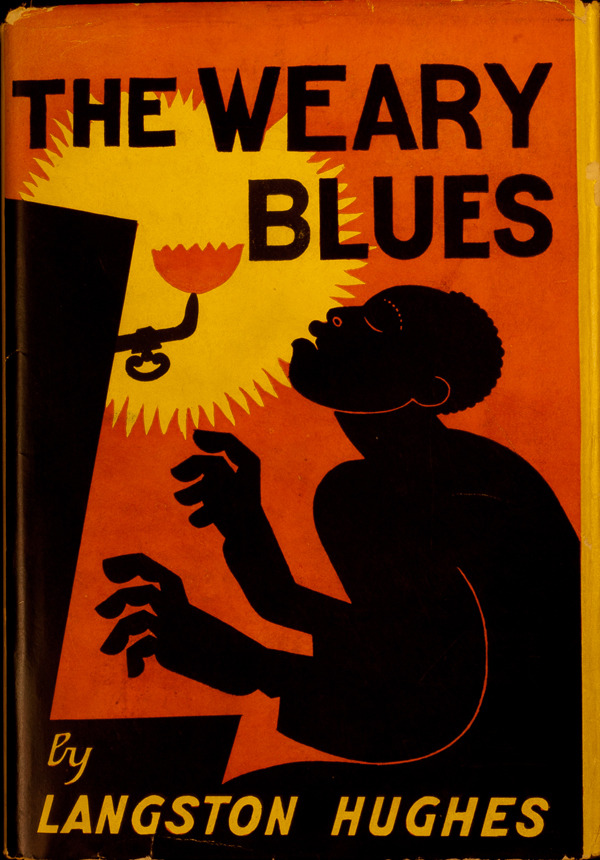

Today’s piece, “Poem” from Langston Hughes 1926 poetry collection, The Weary Blues, is one of the shortest poems in that book. Here’s a link to the text, all of it, if you’d like to read along. Those who’ve followed this Project as it has looked at early English language Modernist verse may recall that very short poems, even poems that seem bereft of obvious metaphor, were something that many of those early Modernists liked to present. Such tiny poems are pointed darts at the pomposity and long-windedness of the poetry they were seeking to replace.

The sense I get from today’s example is that by using the generic if exalted name of “Poem” as the title, when what follows is so spare and simply stated, is meant to draw attention to the provocation that this is worth consideration as a complete lyric.

It may be me and my current situation, but when I read “Poem” I immediately thought it was a memorial poem, a five-line-with-one-refrained-line statement of the essence of loss intended to put itself up against something like the book-length “In Memoriam A.H.H.” by Alfred Tennyson. I still find nothing in the text that forbids that reading.

But death isn’t the only loss in life. Some, particularly those looking for obscured clues to Langston Hughes’ erotic orientation see this a coded statement of a romantic or erotic breakup with a “He.” Like Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence and Tennyson’s long poem, the poem has a dedication to a set of initials: “F. S.” in “Poem’s” case. Some articles one can find in a web search identify this dedicatee as Ferdinand Smith, who was in the merchant marine — as was young Hughes before he published The Weary Blues. Hughes did know Smith, but I haven’t seen a full explanation of how this putative identification was made. Oddly, if this poem of complete separation was written about Smith, Hughes and Smith kept in touch until Smith’s death in 1961. In Real Life there was no utter break between the two — but that’s biographical information, nothing in the text forbids the abandoned love reading either.

Frederick Smith, who’s been identified by some as the mysterious F.S.

.

And then too the poet Hughes of The Weary Blues and elsewhere is very broad in his use of the pronoun I. Not only does Hughes not identify F. S. and what exactly was the nature of the love relationship, Hughes is fully capable of using “I” as a collective or representational singular. Think of Hughes most famous early poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” — its litany of I’s is not a Quantum Leap confession that this certain 20th century poet worked on the Pyramids or rafted the Mississippi with Abe Lincoln.

But “Poem” does feel like a personal expression, even if Hughes may frustrate us if we prefer poems as memoir filled with explicit self-expression. Yet maybe this is of little importance to the essence the poem wants to express. Grief from loss of a lover who leaves and lives, or loss of a friend who has died — does the heart assay any difference?

Musically today I demonstrated fidelity of a different kind, playing a cheap 40-year-old 12-string guitar that I bought shortly after coming to Minnesota, and a bass that once belonged to Dean Seal, who played in the LYL Band in the early 80s. I have newer better* instruments, but it seemed like a good way to reset and get back to making some new Parlando Project musical pieces after February presented other matters that needed to be done.

You can hear my performance of Langston Hughes’ “Poem” with the player gadget below — or if you don’t see that, with this highlighted link.

.

*My newer guitars are better in that they don’t have parts that won’t exactly work anymore or intonation issues I need to work around, but besides old-times-sake I think there’s some character remaining in these funky instruments sound.