We’re going to travel some ground today, so hang on, it’s a longish post.

Today’s piece has an anonymous author. I’ll write a bit about what I can determine about it later on below, but a lot of the time when I write here of my encounter with the words I use as part of this project, I’ll write at least something about the author. Best as I can determine, I care some about who wrote the words.

I write myself, I know the particulars of my life, my outlook and working beliefs, my location in geography and society enter into what I create—but on the other hand, I don’t seem to care overly much about what these largely dead (and sometimes forgotten) writers believe. I’ve performed religious pieces infused with a variety of religious belief, and writings from Romantics, Stoic Classicists, and Modernists from a range of tribes. As I mentioned recently when I performed a piece unconcerned with matters of ethnicity by odd-ball all-purpose British racist Charles Kingsley: I seem open to occasionally read and perform work by writers whose political and social beliefs are for good reasons widely objectionable, and in that Kingsley post I brought up the foremost case in literary English-language Modernism: Ezra Pound, a man who became an overt fascist,* and who aided the other side in one of the most clearly-cut good guys vs. bad guys wars in history.

Would I choose differently if I was presenting work by living writers? Well, I have used words here by folks who are my contemporaries and whose personal lives include considerable faults and whose politics do not align with mine—evidence there again that I may not care enough to exclude the work that seems of interest and worth because of the author’s lack of personal rectitude. I certainly understand why someone would choose to boycott a living artist for unacceptable writings, beliefs, or actions. Once I accept that, it’s an easy extension to extend allowances for boycotters to advocate for others to do the same. Fair enough, even if the specter of blacklists and non-persons can be said to follow. I do worry that the slippery slope tends to flow more forcefully from the heights of power and can be lubricated with money or blood.

But mostly my choices here are selfish. If a work pleases or interests me, if it works for the purposes of this project, I’m likely to favor it regardless of its author. It’s unlikely that I could imagine a work that itself frankly advocates racism, homophobia, or sexism** as having any pleasure for me, while still I know the authors of the words I use are not unfree of those faults. And yes, I worry that some of the tracks of those faults carry into the work I use. Often when I write about those faults in my reactions to the pieces used here, I caution the reader, as I caution myself, that for what we see clearly as condemnable in dead writers, the future and others will potentially find justifiably equivalent wrongs and faults in us.

But then I also believe, roughly, in the progress of civilization. If we find it unlikely that any fault of our time could be equal to the evils of slavery, near chattel status for women, or human sacrifices for religious beliefs, I ask you only to note that intelligent people, capable of creating art that still pleases us, believed or tolerated such things, and we must consider this part of what humans are capable of—even us.

So, what about “Truth Never Dies?” Well, it doesn’t advocate for any particular thing. It does make a claim that activists or advocates who have lost a battle or a war might find comforting, and in its own non-specific way it’s similar to a contemporary motto suitable for coffee cup or t-shirt and attributed to Neil deGrasse Tyson: “The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe it.” And so even for activists working in expectation or demand for immediate action, a Plan B of some future realization of the truth of their request is not unwholesome. No effective movement can exist that can only live and breathe in the environment of success or potential success at hand, it must endure and continue after defeats.

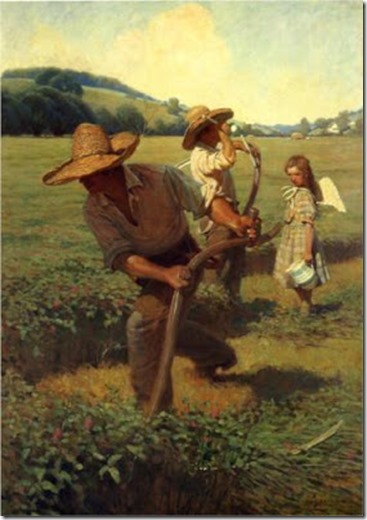

Kenne Turner’s blog will show you some fantastic color photography. The early 20th century Adventist publications which featured “Truth Never Dies” made do with monochrome.

.

As best as I can tell, this poem was likely written in the first decade of the 20th century. It seems strongly associated with American Protestant Christian circles at the time of its writing. The earliest appearances of “Truth Never Dies” I have found are in a 1909 copy of The Northern Union Reaper an Adventist quarterly from Minneapolis, a Seventh Day Adventist publication from Maryland, and several other Adventist publications from that year.*** I’ve also found it in the Adventist The Sabbath Recorder of 1915, a New Zealand based Adventist magazine of 1917, and another Adventist book of 1917 which associates the poem with the visions in the book of Daniel chapter 8.**** A Carolina Mountaineer newspaper from 1917 includes it, and it appears as a prominent embroidered forward to an 1914 issue of Sky-Land, a North Carolina magazine replete with Lost Cause Confederate reverence. The Scientific Temperance Journal quarterly printed it in Boston in 1918. The Bottle Maker, a 1921 trade union publication for yes, bottle makers, (motto: “Labor Will Not Be Outlawed or Enslaved”) features it. A 1922 issue of The Railway Expressman from Wisconsin, another union publication, does so too. A 1941 The Preacher’s Magazine from the Church of the Nazarene in Kansas City includes it. An Ohio-based United Brethren church bulletin of 1947 has it too, and attributes it to another, Methodist, publication.

The poem appears as from two to five stanzas in these publications, and sometimes it’s subscripted with a note “selected” that indicate that it may be a longer poem. I chose to perform just the first three stanzas, if for no other reason than length today.

From the earliest appearances, and some of the imagery of the poem, my guess is that the author was associated with the Adventists. The Venn diagram of Adventist practices and beliefs, temperance, early union movements, and the connections between Nazarene, United Brethren and Methodism fill in the edges.

The most surprising appearance of “Truth Never Dies?” Easily, the November 14, 1981 episode of Saturday Night Live. In a skit with Joe Piscopo and Mary Gross. Piscopo plays Nick the Knock, costumed as if a puppet, in a sort of a riff on the casual comic violence of the Punch and Judy sort of puppetry. After smashing a music record playing the skit’s opening music, he’s visited by a fairy played by the meek voiced Gross who tells him “I like to think I see beauty in you that others are too busy to notice. So I have brought you this: The gift of truth.” The fairy then speaks two entire stanzas of “Truth Never Dies.” The puppet Nick ends the skit by exclaiming to the poetry fairy “I know what I’m gonna do to you, you little thing! I’m gonna eat your spine!” Which he does as the fairy screams. Rather than Daniel 8 or temperance, I’m going to assume that cocaine had something to do with the inspiration of this skit.

How did I run into “Truth Never Dies?” Over at Kenne Turner’s blog this month.

In the end, because we don’t really know who wrote “Truth Never Dies” and because the author doesn’t feel that they need to outline the particulars of a Truth they feel will become self-evident, the poem remains a statement that can be applied quite broadly, and with an effectiveness that remains more than a hundred years after it was written. Readers will not know if they agree or disagree with that unknown author’s vision of Truth, which brings me to one of the things I think I’ve discovered about poetry during this project: that though ideas, including controversial ideas, may be presented in poetry, poetry is more about the experience of ideas than those ideas themselves. So this poem works, not because it’s a religious catechism, a political platform, or a sophisticated philosophical treatise, but because we can read or hear it and share with it’s unknown author the feeling of a truth that will prevail even if it seems underrepresented among the powerful in the world today, or if there are acceptable substitutes for truth that can be endlessly manufactured for short-term tactical benefit.

The player gadget to hear my performance of “Truth Never Dies” is below. Don’t see the gadget. Well, you can then truthfully hear it with this link that will open a new tab with its own audio player.

.

.

*Oh, there are mitigating factors if you had to defend Pound in some debate for points. It was the messier, less efficiently genocidal Italian brand of fascism he aided. It’s sometimes claimed it was all caused by a misunderstood dilettante’s interest in fringe economic theories. And there’s the “everybody was doing it” defense too: he’s not the only literary person of his time to have connections and sympathies to fascism. But let’s face it, if there’s a mid-20th century cancel culture, Pound would be someone we’d want to de-platform. Right now I happen to be reading his ABC of Reading, a book he wrote in the 1930s largely about poetry, coincidently the same time he was finding or writing about his fascist affinities. He has a number of insightful things to say about the art of poetry and the enjoyment of it in this book so far, and I’ve come upon more than one thing where what Pound writes is simply a clearer statement of things I’ve discovered in my own life and during this project about the art of poetry. But he’s also repeatedly making a point I disagree with: that it’s imperative to choose the good art from the bad, and he’s going to tell you how to tell. It’s easy to think that a stubborn insistence in a singular insight into things leads one to larger distrust of democracy along with the ability to hold contrary opinions based on a fixed hierarchy of value.

**Authoritarianism or calls to the purity of violence are heavy lifts for me too.

***Stop the presses! No. What’s the 21st century blog equivalent? Oh, pause the RSS? Rip out the HTML? I’ve just found an even earlier version of this poem, with rarer final verses. Still an Adventist publication though: The Present Truth November 15, 1906.

****Besides Biblical prophecy of the fall of nations, another reference I found to a similar rhetorical flourish was from a 1841 abolitionist speech by Thomas Paul in Boston where he, responding to the notion that abolition’s cause was dying out, said: “Dying away?….Truth never dies. Her course is always onward. Though obstacles may present themselves before her, she rides triumphantly over them….”