Something about the Spring I noticed this year — oddly, this year as an old man who has had a full lifetime of Springs — is the intensity of natural sounds in my city. There’s a tendency, demonstrated in many poetic tropes, to make nature a portrait or a silent movie, putting nature in contrast to the noise of our civilization’s hum and bark.

I ride my bicycle nearly every day off to a café to have a breakfast, sometimes early enough to feel like the single soul on the street, but by the return trip certainly part of the city waking and doing: kids on their school bus stops, sometimes with a parent, sometimes waiting with their own cohort only, folks holding coffee flasks unlocking their car doors to go to work, a few other bicyclists, including those on big front basket bakfiets or long-tail rear-seat-shelf bikes holding small kids, this observant cargo watching whatever in the morning beneath their pastel helmets. The human noise is slight and clicking. In such mornings we are more like crickets rubbing their wings.

But the birds! When most of those humans are making only accidental noise this early, and the kids waiting for the yellow bus aren’t always talking, perhaps practicing quiet for the ordered schoolroom, the birds are singing at the tops of their voices in the morning. Like miniature feathered fiddles, their song cuts through larger sounds, it insists on being heard. “Ladies, I got your genetic material here!” “This is my and my kind’s tree!” “Whatever this is, this Spring, I am here, and I’ll use my breath to say it!”

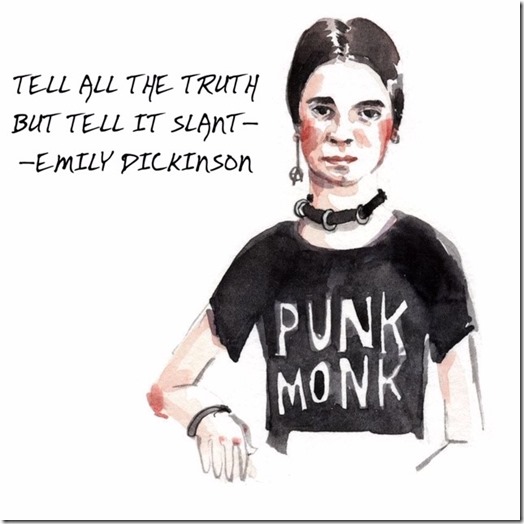

Like us bipeds lacking much fur, other mammals aren’t sounding much. Yard bunnies are suspicious and quiet. The squirrels don’t chirp, and their little feet make quiet footfalls. The dogs on leashes: all nose-leading in an alternate sensory dimension. But the frogs and toads are singing out too — whole amazing choirs of them, all wanting to contest Emily Dickinson’s Nobody with a harrumph and high whistle of who they are.

So, it is this Project’s nature to add sound to page poetry. Today’s audio piece is just me alone with a Telecaster electric guitar during a hurried session early this Spring to put down some musical ideas. In the poem that I’m combining with my music, “The Birds,” William Carlos Williams follows Imagist principles, melding a moment into concrete images. Given that we’ve just had a set of rainy days throughout the long holiday weekend in my city, I resonate as Williams poetically paints the bird-morning wet as undried paint.

Is the world not “wholly insufflated” as he says at the start? The bird song is breathing into our world — nature is not silence, but poetry aloud.

My wife found these* stapled to poles around our neighborhood on Sunday.

.

You can hear my performance of Williams’ “The Birds” with the player gadget below. No gadget to be seen? This highlighted link is an alternative that will open a new tab with its own audio player. Want to follow along with the text of the poem? Here’s a link to that.

.

*This bird couple’s heads are superimposed over a human pair of heads from the cover of The Magnetic Fields Holiday album. The quatrain quoted below is from a song found there “Strange Powers.” Despite being a substantial Magnetic Fields admirer myself, I had never seen this album cover.