I’m thinking lately of the magic of consciousness, of how we exist as distinct limited illuminations of this world for a certain time, and how strange and inexplicable that is.* Is that funny? Tragic? Is that choice just a matter of emotional weather and sensibility?

Today’s poem by Edna St. Vincent Millay is several things. First, I’ve made it the song it pretends to be, but it’s also something of a fairytale, and in sensibility it aims for humor. And since tomorrow is St. Patrick’s Day, we might see it as commentary on Irish culture from a woman’s perspective, even if American-born Millay is not generally thought of as an Irish culture poet to my knowledge.** Of course all poets have, on one level, a single citizenship issued by our international muses, and our work may cross borders at will — even the well-guarded and maintained borders of time. But still, today’s piece “The Singing Woman from the Wood’s Edge,” is going to use some Irish stuff that might need translation for anyone not versed in Irish culture.

“The Singing Woman…” was included in Millay’s 1920 poetry collection A Few Figs from Thistles which largely created the popular persona that launched her to the height of her fame during the last century. Back then they sometimes called Millay an exemplar of “The New Woman,”*** a label which doesn’t tell you itself anything of the novelty implied. Among those traits that might be contained within the term were unhidden intelligence, independence, openness to Modernist changes, and unabashed agency in love and sex. Was this a problem or an advance? The culture of the previous Twenties wasn’t sure, but they talked about it and had opinions. That currency and conversation, that framing, helped Millay to fame, and yet probably constrained her too. A Few Figs from Thistles was read as part of this to a large degree.

A Few Figs from Thistles often used humor within its poems tweaking of conventions, and “The Singing Woman…” is an example of that. Fairytales can be scary or thinly disguised warnings against stepping into the unknown, but this one takes what could be a rather distressing situation and plays it for knowing winks. Since I know this Project has an international audience of varying ages, let me make sure we unpack the cultural particulars of this poem’s tale.

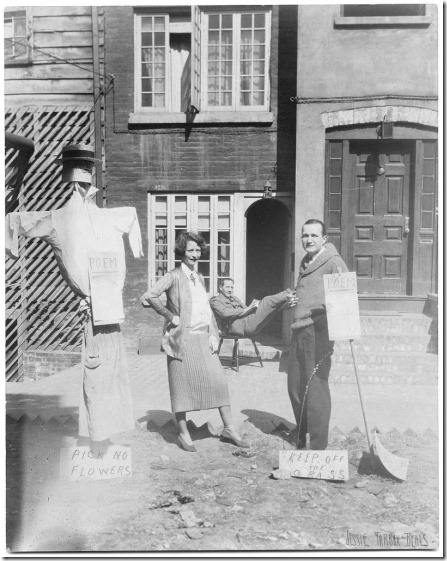

Another spring task to get underway? Millay, her husband Eugen Boissevain, and Edmund Wilson make a point of planting a “poetry garden.” Not shown: plentiful organic fertilizer.

.

The poem is the first-person story told by a child of the union of a leprechaun and a friar. A leprechaun**** is an Irish fairy creature. Leprechauns are solitary (unlike many other fairy types) and are often thought of as being in conflict with humanity, tricking or being tricked by humans. Friars are monks, and in the context of Ireland, we can suspect that they are monks of a Roman Catholic religious order. They too have elements of solitariness, as some monks live in deliberately separated contemplative communities seeking to avoid the corruptions of the material, human world. Oh, and one of those defined corruptions that all Catholic monks are pledged to avoid: sex and marriage.

So right from the second line we can see that the parents of our singer are both impure creatures in violation of their cultural rules, the powers and expectations of which they also apparently retain as the song further portrays them. Though I shortened the poem for performance length by one decorative stanza, a lot gets laid out in the poem, and a great deal of ambiguity and complexity is hinted at in the incidents recounted, even if they are played as a humorous tale. Our poem/song’s narrator, the fantastic mixed race (species even) woman of the title, seems to have chosen to “identify as leprechaun” in effect, but buried in the poem which gives equal time to the cultures she’s experienced from both parents is a sense that it’s more complex than a binary choice. And let’s not miss an important and primary point: both her parents are in violation of their cultures and vows. Regarding the roles often laid out as cultural “or” binaries she “ands’ them: “harlot and a nun” — we can further suspect she’ll choose to not abide either’s rules.

I’m not going to further detract from this piece’s wry humor with more explanations and footnotes. Here’s a link to the poem’s full text, and you may well see a player gadget below to hear a performance of my song using Millay’s words. If you don’t see the player, this highlighted hyperlink will also play my performance.

.

*Which is another way of saying that I’m momentarily unashamed about talking about the inner-directed and odd things that go on in my head as I wish my wife a happy birthday. I’m so grateful that her consciousness and its light has been held near to mine and our child’s.

**I was unaware of Millay’s Irish ancestral roots until I researched that before presenting today’s poem. Similarly, I’m unaware of how often another prominent American poet Frank O’Hara is discussed as having been influenced by Irish culture, despite that echt Irish name.

***See also last month’s celebration of “The New Negro,” the 1920’s other “New.” New is often getting old. On the other hand, a hundred years later, to this old person anyway, it seems like the last Twenties’ assumptions of independence and value haven’t become fully old-and-settled yet. Maybe this, still young and new, Twenties?

****One oddity in Millay’s mythological choices: even though fairies in general have a rainbow of genders, leprechauns are almost invariably presented as unmistakably male. There’s a riddle/joke using the old-style name “Indian” for indigenous Americans: A big Indian and a smaller Indian are walking by a river. One Indian is the son of the other Indian, but the other Indian is not the father of the other. Who is the other Indian?