Before we close the book on National Poetry Month and International Jazz Day, here’s a musical performance of a poem by Langston Hughes. I didn’t think I’d be able to complete it today — but the opportunity arose, and it’s more than appropriate for both observations.

Langston Hughes was one of the founders of Jazz poetry, and that style of reading poetry that interacts with a musical accompaniment (even if it’s not sung) is an influence for some of the performances you’ve heard here in this Project. I can’t say what year Hughes first performed his poetry that way, but there’s another meaning to Jazz poetry without a band: poetry that writes about the experience of Jazz music itself. And Hughes was repeatedly doing that in the early 1920s.

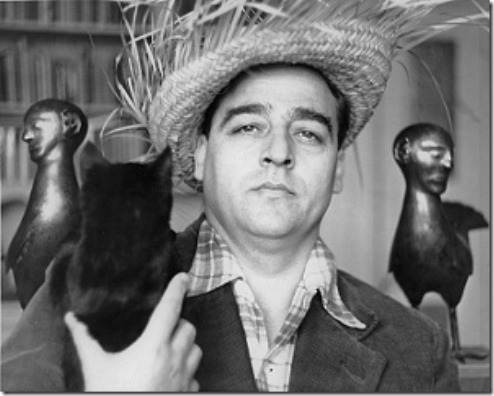

Decades later, a 1950s Hughes reads his 1920s poem “The Weary Blues” in front of a Jazz combo

.

This, a combination that appreciated Jazz, was not a sure thing in the early 1920s. Afro-American intellectuals and cultural critics were not universally fond of Jazz and Blues music, these great Afro-American Modernist musical forms arising right under their noses. There were reasons: it was associated with drugs, drink, criminality, and sexual promiscuity — and none of that promoted Black achievement and excellence in their minds. And some young white folks were taking an interest in Jazz for those very reasons. Tut-tut voices from both racial camps were observing their young people and thinking it was all about mindless, hedonistic partying. Let me repeat myself: when the last decade to be called “The Twenties” was called “The Jazz Age,” it wasn’t meant as a compliment.

I’d suspect this isn’t widely known to many readers. Jazz, to our 21st century Twenties, might be felt as supposed-to-be-good-for-you-but-boring-art music made up of too many weird chords and snobbish old men with a fetish for instruments you blow into. If we take it too seriously, too often now, the problem in the 1920s was they didn’t think it had a serious bone in its body.

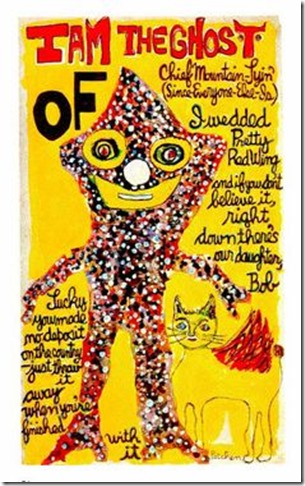

Maybe it helped that Langston Hughes was a young man, a teenager when the 1920s began. He appreciated things in Jazz and Blues that even his Afro-American elders didn’t see. He knew it could be a balm to pain and disappointment, its expression and expiation — and he could see the art in it, an art to wrap into his poetry. This small poem of his, published in 1923 in the W.E.B Du Bois/NAACP The Crisis magazine, hears something others couldn’t: he hears a Jazz band cry — or rather his poem reports a woman heard this. Here’s a link to the full text of the poem.

Even in the shortness of his poem, note the dialectic here. The band, earlier in the night, had dancers, “vulgar dancers” it says. The older cultural gatekeepers at the Crisis would agree as they accepted this poem, “I see the young poet is aware of the dangerous moral unseriousness of the Jazz hounds.”

Why could Hughes hear what others didn’t? Well, he’s a great poet, and a poet that wrote often and empathetically of other people’s experiences. There’s another possible element. Do modern ears hear the poem’s second line differently than his readers in the last Twenties? “They say a jazz-band’s gay” he wrote. “Gay” in the 1920s would have clearly meant “happy.” As far as scholarship understands this, gay=homosexual seems to have come into use a bit later, perhaps in the 1930s, and to general readers, that meaning emerged in an even later era.

Hughes’ own sexuality is not something we know a lot about. Some say he was gay, some say he was asexual. One thing I get from reading Hughes’ early poetry is that he’s hearing and telling his stories not just from a stereotypical straight masculine viewpoint. Is it his anima that’s the she who “heard the jazz-band sob” in the poem? Or is he just listening to a woman?

Well, my performance of Langston Hughes’ “Cabaret” is ready to be heard. Unlike the last piece, I made no pretense of Jazz music as it’s classically understood this time, but I do throw in some weird chord extensions. You can hear it with the audio player below. No player to be seen? The dancers have left, and some ways of reading this blog suppress the display of the audio player. If so, use this alternative, a link that will open a new tab with its own player.

.