Our last poet, Margaret Widdemer seems to have done most of her adventuring in fantasy, but today’s poet, Elinor Wylie—well, she caused quite a scandal in the pre-WWI years. Widdemer may have dreamed of cavaliers and wearing leather in a traveling Romany wagon; but for Wylie, there’s biography! Elinor Wylie grew up in Washington D. C. the daughter of Theodore Roosevelt’s Solicitor General and infatuated with the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley, which, as we’ll see, could be a bit of a leading indicator. Elinor Wylie started right off by eloping with another would-be poet, Phillip Hichborn, shortly after high school. They had a child, but the match was not good, and the brief accounts I’ve read report the husband as “unstable” and “abusive.” Next, her story gets weirder. An older millionaire lawyer Horace Wylie, also married, began to, as Wikipedia puts it, stalk her. Again, I lack details, but he apparently followed her about, taking care to show up often wherever she was. I’m not familiar with dating etiquette for married people in the pre-WWI era, but this sort of thing began to attract notice.

Bad marriage. Stalker. What to do, Elinor? She ditched her husband and fled to England with the stalker. Now we have full-fledged scandal. They hid out in jolly old for a while under assumed names. President Taft reportedly made efforts to bring her back. Eventually Horace Wiley got a divorce, Elinor’s first husband Phillip committed suicide, and WWI broke out in Europe. The run-away couple returned to the US, got married, and settled in New England where according to one biographer “Shopkeepers boycotted her, and she could buy no food. People began to turn away from her in the street. [The Wylies] were ignored in the worst way possible.”

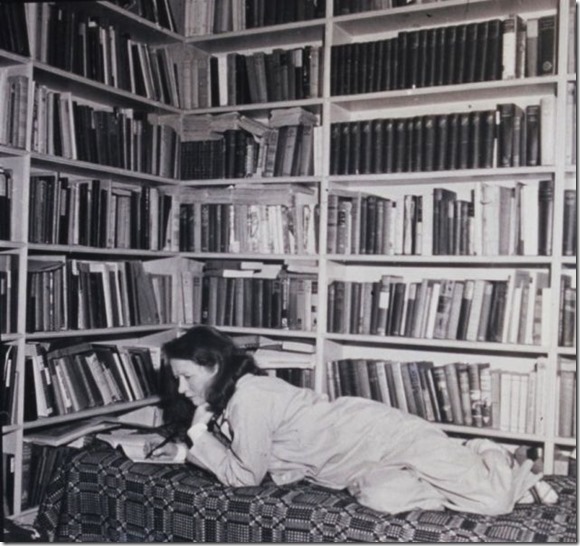

Back in the US, the marriage to Horace Wylie soured too. She was to have one more marriage, this time to Stephen Vincent Benet’s brother William Rose Benet. They eventually separated, but Benet continued to promote her literary efforts, until in 1928 at the age of 43, the writer, still writing under the name of Elinor Wylie, died instantly of a stroke at Benet’s home while looking over pre-publication galleys of her last poetry collection with him.

Elinor Wylie, clean bones crying in the flesh

All that folly of love in one short life! Did she manage to produce any poetry worth noting? From a look at her first collection, written largely while she was still married to Horace, I found her poetry more immediately attractive when read in the present day than Widdemer’s work. It’s very concise, and often considerably musical. You can see the influence of Shelley in the intense feelings and in some of the elaborate word choices. During her lifetime, the musicality of her verse (like Teasdale, like Millay) was noticed and admired, but like all three of these skilled singers on the page, High Modernism eventually discounted that element of poetry and looked for grander, more elaborately worked-out themes. And, to be frank, it also seemed to be looking for men. Mid-Century Modernism was a boys club.

Unlike Shelley, when time and death wore out the notoriety, the poet was more or less forgotten.

“Full Moon” shows Wylie’s concise intensity well, and it shows a flair for visceral imagery too. In search of music or from love of obscure words, Wylie crafts lines that sound great even if one must keep a dictionary window open to grasp their gist. The poem as vocabulary test, a bit Wallace Stevens-like. Lines such as “My bands of silk and miniver momentarily grew heavier” and “Harlequin in lozenges” start the first two stanzas. Miniver? I think only of a Greer Garson movie. It’s a fur coat lining. Harlequin, a stock pantomime clown/fool character sure, but what’s with the lozenges, is the harlequin mute because of a sore throat? Nope, lozenges also means diamond shaped, the traditional harlequin costume has a diamond pattern.

Harmoniums without Wallace Stevens: Nico and Elinor Wylie

What’s it all mean? It’s not hard for me to see Wylie’s biography in this, the experience of being seen as the bad woman, shunned and condemned. I made a mistake in performing this, singing “carnal mask” instead of the more perfect rhyme Wylie wrote: “carnal mesh.” I noted it right off and tried to sing the verse again, correctly, but I ended up liking the mistake and left it in. Musically, a Nico solo record from the mid-20th Century vibe came out, as I could hear Nico singing something like “harlequin in lozenges” and getting away with it a half-century after Wylie. To hear my performance of Elinor Wylie’s “New Moon” use the player below.