I suspect no poet in the past couple of centuries has suffered a greater decline in esteem as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. This is not due to some scandal in his biography, for as far as I can tell he lived an admirable life, but artistically he’s been indicted for a number of crimes and misdemeanors. Before I go over those, let me briefly summarize the heights from which Longfellow has fallen.

He was the first self-sustaining professional American poet, the first to reach a considerable level of national and international success. By the middle of the 19th Century he was roughly as famous as Tennyson and Dickens, known and generally admired by his contemporary poets, and avidly read by a broad non-academic readership. He sustained this fame for several decades and further, past his death in 1882. His general readership survived into my grandfather’s generation, and then through my father’s, and to a degree, into mine. Somewhere in the middle of the 20th Century, this engine of fame and readership broke down, and by now they’ve torn up the tracks of the Longfellow Line, and ragged grass grows over the railbed.

I grew up reading Longfellow as the next generations might read Dr. Suess or Sandra Boyton in childhood. As I reached the age of ridicule, I could revel in Bullwinkle the moose in his parody poetry corner reciting Longfellow poems that I knew. Now Longfellow is probably not well enough known to satirize.

So, what are Longfellow’s poetic crimes? Meter and rhyme and a certain amount of antique diction—though we are able to somewhat forgive the English romantics of the generation before Longfellow those afflictions. Earnestness and popularity, two things that no ironic 20th Century Modernist would wish to be accused of—but Robert Frost survived the later, while being seen (mistakenly) as expressing the former. Longfellow’s contemporary, Walt Whitman, explicitly sought to commit the earnestness and popularity crimes—though, as the old dis goes, for many years, Whitman couldn’t get arrested for it.

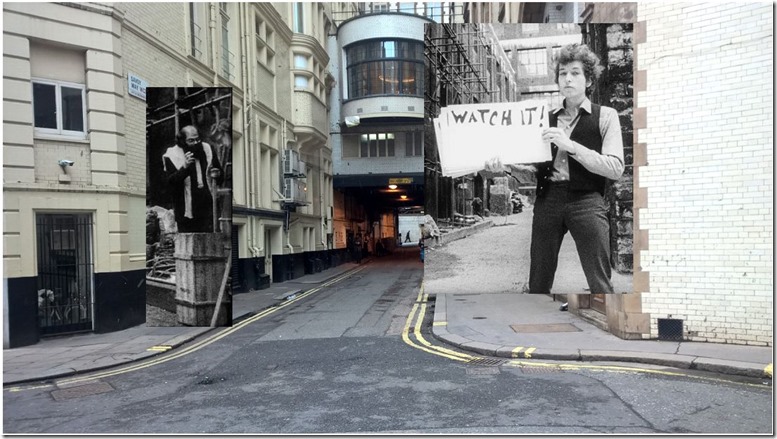

The good gray poet Whitman, and his doppelganger the forgotten famous writer Longfellow.

But Longfellow’s capital offense, the crime his reputation has been executed for, is simplicity and conventionality of thought. If I had to be Longfellow’s defense lawyer on this charge, perhaps I’d be reduced to throwing his case on the mercy of the court. Longfellow’s writing is often expressly didactic, and impersonal sentimental themes abound. Over and over again, he counsels perseverance and its seeming opposite, acceptance of impermanence. A more metaphysical poet would show his work and do more with incident to earn his conclusions. A more modern poet would make sure to make his life’s painful particulars his main subject.

Ironically, Longfellow’s life story is full of such material. Today we often think of poetry and art as an extension of memoir, and that writers earn their license to express things from their life stories. Longfellow would have had that license.

Some forms of Modernism believe that the best way to deal with complex emotion or great pain is to put it in the silences, in the blank spaces. These Modernists believed this would be more effective, because they are signaling with this constrained and minimalist expression that the thoughtful audience needs to seek for what is not said.

20th Century Modernists decorated their foreground with images, not antique forms of literary expression, and the complex message is encrypted in those images as if by steganography. Could Longfellow be doing something similar in the blank spaces between the lines of his hypnotic verse?

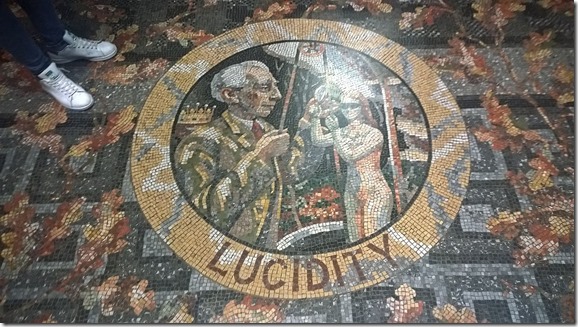

Today’s piece uses words from a late Longfellow poem “Morituri Salutamus,” a Latin title taken from the famous gladiator phrase “Those who are about to die salute you.” The bulk of this poem, written for the occasion of his 50th college class reunion when Longfellow was 68, is taken up with matter that might appear in a commencement speech or the granting of an honorary diploma. Its purported mode is lightly elegiac, advice to the young is given; but as it proceeds, Longfellow transitions to a not over-worn thought. He prepares for the poem’s final stanza by cataloging some swan-songsters of literary history: Simonides, Chaucer, Sophocles. For compression, and for my preference for briefer work, this last stanza is what I used for today’s piece.

In that final stanza, with supple verse, Longfellow concisely implores his aging generation (and himself) to continue to labor to create, to create better. That’s not a complex thought. Does it need to be? Is it easier or tougher to do because it’s a simple thought?

To hear my performance of the conclusion to Longfellow’s “Morituri Salutamus,” use the player below. Some of you will not see the player, but then this highlighted hyperlink can be used instead to play it.