How faithful should a translation be? I can hear your first answer even over the silence of the Internet: “As faithful as it can be, of course.”

And there are many times when I wish it could be so. One has to accept the translation loses when the devices of one language can’t make it over to the new one. Then, often there is the decay of time and the distances of cultures, and this can make meaning murky and less vibrant—but even between two people, of the same time and culture, native speakers of the same language, misunderstanding and misinterpretations of poetry occurs, as you can see with some pieces here where I perform words written by alternative reader and LYL Band keyboardist Dave Moore, which I didn’t fully grasp.

In the next two episodes of the Parlando Project, I’m going to demonstrate two different paths I’ve taken with the same poem, Rainer Maria Rilke’s “The Dark Interval.” Today’s version is an attempt at a faithful translation.

Looks like kind of the intense sort: Rainer Maria Rilke

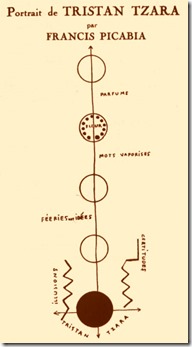

Rilke, like Tristan Tzara or Apollinaire is another one of those WWI area European artists who exact nationality is hard to pin down. Is he Czech, Bohemian, Austrian, German, Swiss? It’s doesn’t help that the maps of Europe were being redrawn during his lifetime by the outcome of the WWI.

Nor does it help our translation task that he wrote “The Dark Interval” in German, the language that one set of my grandparents spoke in their youth, and that even my mother was somewhat fluent in as a child, because I know even less German than French.

And Rilke is philosophically dense. His poems are full of compressed thoughts about the inexplicable, and he has a strong spiritualist bent. The former makes it hard for anyone to marshal his thoughts into another language while impressing on you the need to do so; the later makes it harder for me in particular, as I have come to believe that a philosophical spirituality is (at least for me) an impediment to approaching the mysteries.

It may help that I first encountered Rilke’s “The Dark Interval” in a way deeply integrated into life. I, along with my friend John, was watching a band, The New Standards, perform in 2006, and during an interval in their show a man (who name I should remember, but can’t) read this poem. He did a good job of it, transmitting something of Rilke and himself in his reading. The translation he read was somewhat like the one I made later, and perform for today’s piece.

Just to give you a flavor of that concert, here’s the first piece they played. They did not pre-announce the song they were covering, leaving us in the audience to recognize it as their very different version unfolded:

I heard the Rilke poem immediately then as a meditation on the hurried mid-lives that John, I, and perhaps many of the audience were living at that time. Perhaps he—or the band performers, largely composed of veterans of locally famous indie rock bands of the 1980s and ‘90s—selected it for just that reason.

That’s not the version I perform here today. I did not change the words of this first translation, which sought to be faithful as I could understand it to be to the original German words, but circumstances changed how I hear it. John died, unexpectedly, way too young, a short time after we attended that concert. I learned later that Rilke composed it as he began to suffer from his final fatal illness. I can now see this not as a work about the busyness of middle age, but a work about the busyness of living nearer to dying. Different poem.

Here’s my performance of Rilke’s “The Dark Interval.” Just use the player that appears below to hear it. Tomorrow, my second translation of the same poem, with a different performance.