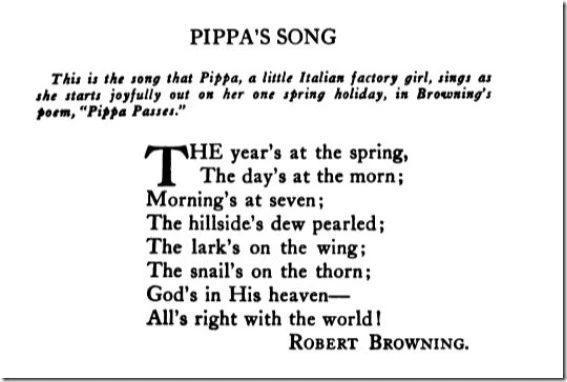

One never knows where strangeness will arise in this Project. Take today’s piece, which I thought was the most routine little poem in a pair of 1920s anthologies of children’s verse I’ve been exploring this National Poetry Month. I wrote down Robert Browning’s “Song from Pippa Passes” as a candidate early in this process. It’s short. It claims in its title to be singable. It contains a well-known line that’s so often repeated we may have forgotten it came from a poem. Those are all good things for a Parlando Project piece. In the context of my planned series, I figured this innocuous poem could stand for the elements of the innocence of childhood portrayed in The Girls andThe Boys Book of Verse.

Here’s the childhood context known and unknown for the editors of these books in 1922. There was much change afoot:

- The United States had emerged from a pair of overseas wars — the second, WWI, broader and more deadly.

- World maps had been redrawn. Kings deposed and monarchies ended.

- American women had just gained the right to vote.

- In the arts Modernism was breaking through, music and poetry took on forms that seemed formless.

Children are born into a world they know is new only by definition, but their parents, the ones who’d purchase such books must have sensed these changes. Is this poem a way to rest from all that change?

And then there’s what we know, but the editors would need to be prophets to foretell to those children starting to read or be read to:

- The world would soon be plunged into a widespread economic depression.

- Totalitarian dictators as cruel as any evil historical monarch would arise with popular backing.

- A greater and more widespread world war was to come as these children reached young adulthood.

- That great war would end with a fearsome weapon’s deployment and a cold war standoff between two global alliances.

Could they repeat this poem later in a breadline, bomb shelter, or landing craft?

So far this month we’ve learned that the editors would include poems of blood, murder, war, and strife. These weren’t considered off-limits for children. They would almost completely ignore Modernist poetry however (save for our special child prodigy exception). There would be some poems of adventure in the girls volume, but more poems in the realm of imagination, and no notice of women at work (though there’s little about men at work in the boys volume either). The boys volume would have sections of poems on war and battles, and another section devoted to “words to live by” poems of virtue. The girls were not given a similar section of poetic instruction. *

A thorough introduction? It does show that the editors had knowledge there was a context to this short poem. Now read the rest of this post.

.

And Browning’s little poem? Well at least I won’t have to do any research for it. It’s just a poem of Springtime childhood safety and innocence. I think I ran into the poem in schoolbooks in my youth, and it was never explained as anything other than that. Well, I have to write something about it now. Let me check.

OMG, in heaven or otherwise.

Turns out the verse drama the song comes from is a nasty little piece of work. Smutty adultery, political assassination, trickery, dirty deeds done with wills and waifs. I read the first act, the part that includes this well-known poem. It portrays a scene between two adulterous lovers fondling each other and panting about their ardor. We learn this bodice-ripping ceremony celebrates that they’ve just killed off the third-wheel husband. The Pippa in “Pippa Passes” wanders by singing our 8-line ditty, and without an ounce of explanation on the part of Browning, the adulterous man kills the new widow and himself out of guilt for — well, it’s complicated — guilt for being seduced by the hot wife, not thanking the dead husband enough, and maybe a little for the murdering part, though obviously the song has occasioned him being up for some more murdering.

TL:DNR summary: more “Double Indemnity” than “Mr. Rogers.”

My reading? Browning’s intent, however ham-handed, was to draw bitter contrast between humankind’s fallen state and Pippa — a poor, innocent, factory girl, who’s passing by these scenes of mayhem on the only day-off she gets in a year. To give Browning the best I can give him: the total incongruity of this tiny song that ends “God’s in his heaven — all’s right with the world” moving the plot to some new if not exactly benign resolution is Brechtian a century before Brecht.

Now here’s what’s strangest. How the hell did this become a popular short poem all on its own as just a piece about Springtime happiness? What’s the path here? Was there a shortage of happy short spring poems? Did someone misunderstand it and promote it as such? My musical performance is left with just trying to make this set of happiness words seem vaguely strange. I’m writing this in a world with manifest suffering and dutiful cruelty explained by “You don’t understand, we have reasons and rules that prescribe that suffering.” We are slow as snails on that thorn. So, I had help.

The audio player to play my performance of Robert Browning’s “Song from Pippa Passes” is below. No player? This highlighted link will open a tab with its own audio player.

.

*My wife galsplained this: “Girls were supposed to be just naturally good and virtuous.” If you’re wondering why I didn’t prompt you to guess if the poem was from the girls or the boys volume of these poetry anthologies today, this is another one that was in both books.