On the page, and probably in my recorded musical performance, this poem is an odd combination. Here’s a link to the text of Claude McKay’s “The Tired Worker.” Its subject is altogether common: the fatigue of someone who is overtaxed by their job, and a night whose worry and weariness has paradoxically robbed them of enough rest to hope for a better tomorrow. Claude McKay, the author I’m featuring this month, knew these feelings firsthand from the jobs he’d held to support himself as a newly landed US immigrant. I dare say most who read this poem have had nights like this too. As poem subjects go, it’s likely as broadly relatable as love and desire.* McKay doesn’t go into detail what kind of work the poem’s titular subject does – but calling them a “worker” and expressing their experience of tired hands and aching feet would indicate a manual labor or a service job.

And here’s what strikes me (and perhaps you) as odd, encountering this in my 21st century time: the poem is written in flowery, elevated, 19th century language. For a 1920’s worker to speak of their daily lot as if it’s an 1820 poem contemporary with John Keats seems anachronistic. I’m trying to think of what a current equivalent of this would be, and maybe that’s impossible in that we can’t see, as we can with history’s perspective on McKay’s poem, how out-of-place this poem’s language is with the daily language of its worker or worker-reader.**

That this poem was first printed in The Liberator, a radical socialist publication founded and edited by Max Eastman may be one clue. I’ve spent a few hours this week paging through its early 1920’s issues published from within the Greenwich Village progressive ferment of its time.

I’ve been fascinated by this scene, partly because I had a shirttail relative Susan Glaspell who was an integral part of it, but also because it was a rich mixture. Political, sexual, and artistic radicalism were literal bedfellows. The Liberator featured a great many ads for political tracts, but also for literary books, and many of latter were low-priced reprints aimed at a bohemian’s or workingman’s budget.

Doomscrolling in the 1920s? Michael Angelo’s Sonnets, Tolstoy, William Morris, Shaw, Voltaire, Wilde, and Nietzsche. Also socialism and the story of what Karl Marx did during the American Civil War. 10-50 cents a piece, or all 50 for $4.75. If one can’t sleep after a long workday, such a TBR pile near your bed could reach out to you.

.

And in between John Reed and Eastman’s first-hand reports from the Russian Soviet Revolution, there was much art and poetry. The art included political/social satire cartoons, illustrations/posters (often in a bold style depicting heroic workers or radicals,) and black and white art depicting nature or the human form. The latter was Modernism of a kind, though I don’t recall much full-fledged abstract works. The famous NYC Armory Modern Art show was nearly a decade past at this point. Carl Sandburg*** had won a Pulitzer in 1919 for his Imagist and free-verse poetry. From the same NYC scene as The Liberator, Others: A Magazine of the New Verse had completed its 4-year run publishing avant garde poetry. Yet, there was much less free-verse in The Liberator than one might expect.

It turns out The Liberator founder/editor Eastman was an early opponent of literary High Modernism. **** If the world and society needed to change, change radically, the old verities of prosody could still serve well to elevate mankind as they strove for that change.

Did Claude McKay feel the same way? I don’t know enough to say. During the early 1920s, he’s listed as an editor on The Liberator’s masthead. Its broad progressive outlook generally supported racial equality, and the NYC Harlem Renaissance and the Greenwich Village scenes overlapped.

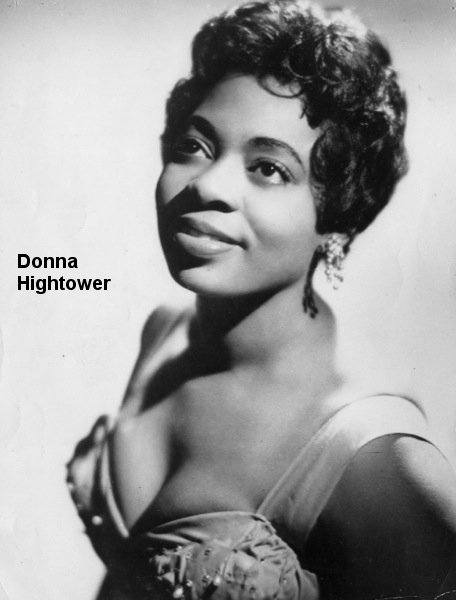

Claude McKay and Max Eastman

.

Is that why McKay wrote his worker’s poem this way? There could be more to that choice – he apparently liked the sound of 19th century British verse; and knew how to extract some word-music beauty from it, as I hope examples I’ve performed may show. Perhaps he felt he was expressing his own soul existing within that workday fatigue – he wasn’t some generalized Worker, but his own particular self, Claude McKay, a man taking pride in knowing this part of his received culture. If so, a man, an Afro-American man, could express that dull proletarian grind with the same word-sounds that once extolled Grecian urns and English nightingales.

Yet, there’s a palpable disconnect here, and I was going to perform the song. I decided to just do my best to not linger on its anachronisms, the “O….thou.…wilts” of this poem. Maybe, the combined character speaking here as I performed it in 2026 is a man living in three centuries simultaneously while speaking in the manner of one class while living in the manner of another. McKay may be not so much colonized, as a colony-creature, a siphonophore banding together more than one mind and tongue. As I wrote talking about McKay earlier this month, poets are often, in effect, immigrants or exiles by their natures, souls seeking and divided from the world and nations they find themselves in.

You can hear my musical performance of Claude McKay’s “The Tired Worker” with the audio player you should see below. Has the graphical player gadget said screw-it and called in sick? No, some ways of viewing this blog suppress showing the player, and so I offer this highlighted link that will open a new tab with its own audio player.

.

*Once more I’ll remind readers that I’ve encouraged something I call “The Sandburg Test.” The test is to ask, does at least one poem in any substantial collection of poetry deal with the world of work? If you’re reading a Carl Sandburg collection, the answer will be yes. Other poets? Well, read, and ask yourself.

**The closest I could come up with would be the trope of some Americana artists of adapting decades-older styles of music and lyrics to express modern problems – but most of those borrowed styles are less formal and more-or-less reflect working-class speech of the past times.

*** Socialist and free-verse Modernist Sandburg did publish at least one poem in The Liberator. And for contrast, here’s Sandburg taking his Imagist approach to the same subject as McKay’s poem.

****Eastman is a character I don’t have room to go into today. Escaping by the skin of his teeth from the grasp of the first American Red Scare as an editor of The Liberator’s radical forebearer The Masses in 1917 – that magazine was shut down by the federal government and he was arrested, charged, and tried with only a final hung jury keeping him out of prison. His long life saw him continue to resist the rise of obscure Modernist literature, while moving from founding fiery left-wing magazines in the WWI era, to becoming an editor of the Readers Digest during WWII, to contributing to the post-WWII launch of the conservative The National Review. and to at least qualified support for the second great American Red Scare in the 1950s.