The recording of this musical version of a short Robert Frost poem somehow was able to slip itself in-between standing watch, comforting, and grieving this month in Minnesota. Increasingly people outside our area are expressing admiration for our fortitude, but inside our local theater of atrocities, I’d say our thoughts and feelings are still a jumble. My aged body has its limits, but I’m trying to support others during this time. Things you might see here? I still find it difficult to integrate these events into the long-ongoing Project.* There’s a great deal of news coverage and analysis being done elsewhere, but during this time you have been spared hundreds of words I’ve written and then not posted, longish things where I sought to add to that. My audience isn’t that large; my remaining skills in prose I’d self-assay as not unique enough to be required. My Parlando Project creative time is constrained both internally by aging and my acute reactions to the present crisis, and externally by limited times when I can use some musical and recording tools.

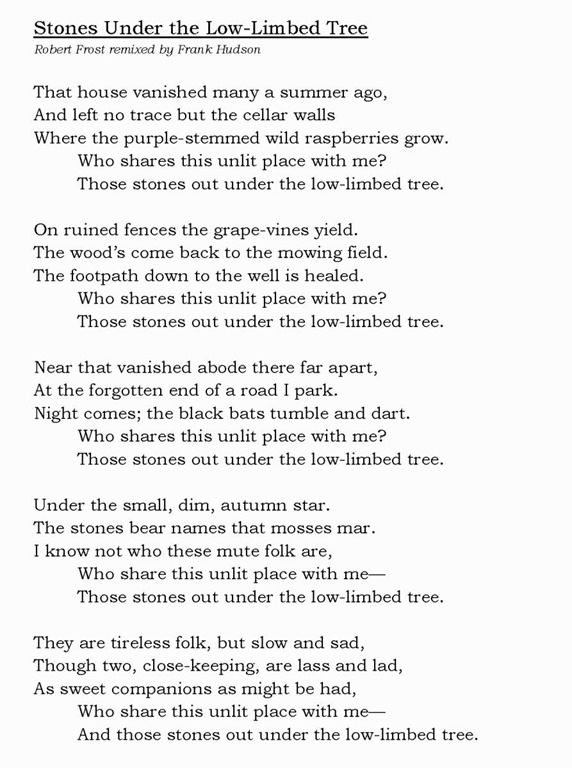

Yet, somehow, this piece is here today. Does it address the events here this January?** I think it does, at least partially, but first here’s a short account of how it was made.

I’ll skip the details, but the present recording logistics here limits the ways I can record guitars, though guitar is the instrument which I have the most facility with. Electric bass, my “second instrument” is easier. Recording an electric bass by directly plugging into a jack in an audio mixer or interface has long been a best practice for everyone from home recordists to pro studios, and since there are no amp speakers in the chain and a generally inert plank of wood holding the plucked strings, this is near silent in the room and it eliminates microphones capturing unwanted noise. Electric guitar can be recorded the same way, but for some stylistic choices you want the guitar to react to sound coming out of a speaker – and furthermore (for me, anyway) I express things differently when I’m moving air loudly in a room when playing electric guitar. This doesn’t factor into playing bass. So “A Minor Bird” started out with me working out a computer drum pattern and playing a bass line. I created a chord cycle based on the bass line (the reverse of how I often do it) and used a computer piano to create a MIDI piano roll expressing those chords.*** I then edited that MIDI score to get a part that pleased me. I next hacked playing a Hammond B3 organ part myself with my little plastic keyboard, though mercifully, all you will hear are the best bits. The next track was my singing Robert Frost’s words. Each of these steps could be done in the odd hours I could grab, so the song took form in dribs and drabs over a few days. I had intended to overdub an electric guitar solo in the middle, but that time wasn’t there, which leaves the drums/bass/piano trio grooving alone, which might even be addition by subtraction.

This Frost poem is not one of his better-known ones, though published in his 1923 collection New Hampshire, the book that won his initial Pulitzer Prize. The first thing that struck me about it is how modest and unassuming it is: four couplets long, no exotic words, a vignette with two characters: a bird and the poet/speaker. I would almost say that there is no prerequisite reading or coursework needed to understand the poem, but my next thought was that the situation here, poet and a single bird, might be in conversation with other poetry. One could think of other romantic poems of a poet and birdsong – Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale” for example – but if I was to think of a single poem that Frost is writing his in conversation with, it would be Poe’s “The Raven.” Both poems are set in the context of the faceted emotions of grief/melancholy/depression. Both have the poet wanting the bird to leave, but despite the shortness and plain language of Frost’s poem, there’s room in his short poem for a volta, a turn of thought. Frost never names the species of bird, but by calling it “a minor bird” in his small poem, he’s also explicitly casting the bird’s song as being in a (sad) minor key. The poem’s conclusion is that the calling of grief and sadness should be included in our consciousness.

Saturday, after the latest killing of one of the observers who was filming the actions of the Federal troops elsewhere in Minneapolis, other observers in our neighborhood and their families gathered in the below-zero dark on our streetcorner, each of us carrying a candle from our houses.

.

The doorknob where I write this has a lanyard with a whistle. It’s to grab, to take outside in the winter cold and to make our minor sound at anything from the incursion into our city that calls us to flock witnesses too. This state in this country, and this composer and plain singer of Frost’s words, have had their griefs this month. We have chosen not to shoo them away – despite the raptor dread encircling our minor birds, we have not silenced the song.

To hear the performance of Robert Frost’s “A Minor Bird” use the audio player below. No player? Nothing has caused it to withdraw, it’s just that some ways of reading this blog won’t display the player. This highlighted link will open a new tab with its own audio player.

.

*Perhaps I’m an odd duck, but to release art about these events worries part of me that some portion of the artist is seeking to use these largely selfless and unsigned acts of resistance as a platform to promote their work.

I’m not saying you should feel that way! And yes, I am quite aware that conversely some artists and their work have been down-rated, suppressed, and punished due to their art for causes.

My feeling is more akin to the idea that in either case, the thoughts of pros and cons of careerism must be humbled by the everyday bravery and service Minnesotans have shown this month.

My one art-for-cause step so far has been to release alternative Parlando Project voice Dave Moore’s re-casting of Wendell Phillips cry about fighting injustice, “I’m On Fire” from 2014. Thanks largely to some folks reposting it on BlueSky it’s garnered more than usual listenership.

**Under what name will this month’s resistance be recorded under? “The Battle of Minneapolis” has already been used for a 20th century labor action. I’m fond of wordplay, but “The Mother Whistlers” is too humorous. “The Minnesota Witnessers?” “The ICE Breakers?” “The iPhone Militia Movement?”

***MIDI notation makes-do for this naïve composer who tried to learn musical notation decades ago, but largely passed it by. Something in me loves it is the computer adaptation of the paper piano rolls such as my grandmother’s player piano or maverick composer Conlon Nancarrow used.