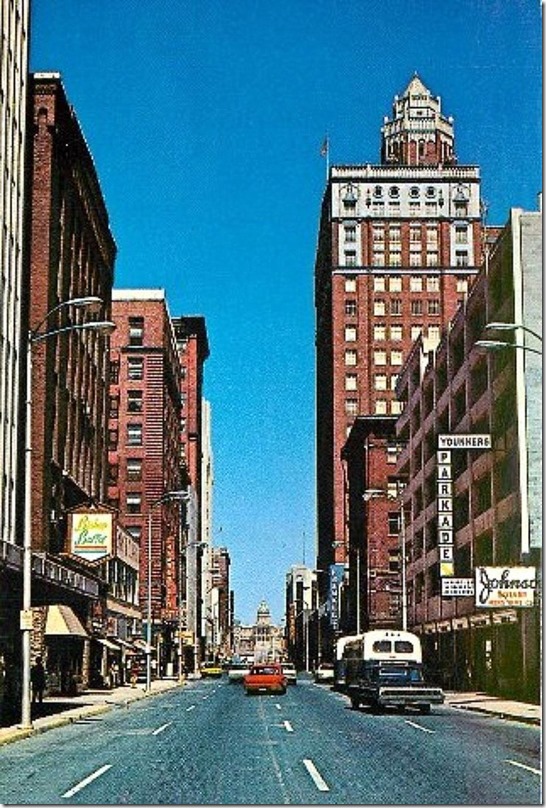

I have to hand it to the Victorians — when it came to the names of some of their poets, they seemed to know how to roll right through the evocative, and tumble ass over teakettle into camp.* This project has touched on the Pre-Raphaelites, those 19th century hipsters with their love for the middle-parts of the Middle Ages, and one of their leading lights Dante Gabriel Rossetti had a moniker that seemed to mix angels and demons with some flowery notes. Or then there’s the pioneering Canadian poet who decided to flesh out Sappho’s fragments with his own poetry: Bliss Carmen. But let’s suppose you’re writing a comic novel set then. You want a character name that’s really, really over the top. If so, you might then independently invent the name Algernon Charles Swinburne.

Sorry, already taken.

I can remember first running into the name in a poetry anthology while a teenager. I laughed out loud at its outrageousness. Algernon had been dead for a bit more than 50 years, but as we shall see, I doubt he minded my noting that. Honestly, I laughed for myself, but of course as a teenager who liked poetry I may have needed to laugh at that name out loud too. Young men in my place and time weren’t much for poetry, but I could suppose a name like John Keats could slip under the radar. Algernon Charles Swinburne, on the other hand, could have written poetry like Robert W. Service and he’d still have such a foppish name.

I went to read his poems anyway. Or I tried to. They didn’t seem outrageous to me — their effect was more at ornate, over-decorated boredom. And his poetry seemed to have nothing to say other than its fancy dress. In the years since, I’ve occasionally looked at a few Swinburne poems, and nothing has changed that opinion.

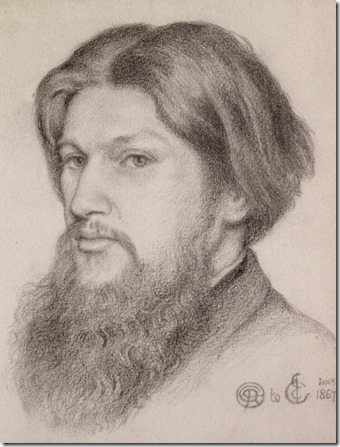

Portrait of Swinburne by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Let’s forget poetry for a moment, what product does he use for that much body?

.

This year while reading some accounts and memoirs of early poetic Modernists I did notice something odd. More than a few of them went through a Swinburne phase.** I had known that the Pre-Raphaelites (Swinburne knew and was associated with them) and their “Forward Into the Past” revivalism of earlier literary and visual styles was an influence on some Modernists, but the things they sought to revive tended to be simpler than the mainstream Victorian style: old ballads, flatter painting, hand-hewn furniture, that sort of thing. Swinburne just seemed rococo through and through.

But there was another element that may have attracted them. Swinburne’s poetry was considered in the late 19th century to be, well, hot stuff, erotic, even transgressive. Swinburne’s contemporaries thought that Swinburne if anything reveled in those characterizations. Oscar Wilde (here we go again with the Victorian names) might be thought as someone comfortable with this, but more than one article I’ve read notes that Wilde said of Swinburne “A braggart in matters of vice, who had done everything he could to convince his fellow citizens of his homosexuality and bestiality without being in the slightest degree a homosexual or a bestialiser.”

School poetry anthologies skipped over that part, but Swinburne’s indirection in his poetic diction isn’t going to cause me to create a “radio edit” of today’s piece, his love sonnet “Love and Sleep.***”

So, what’s going on in this poem? S-E-X of some kind, though the down and dirty details are hard to suss out. A lot of what you may “see” in it is portrayed by implication and connotation. The “nudge, nudge, wink, wink” elements of the famous Monty Python sketch can be invoked in close readings here. I don’t want to play the Eric Idle character from that sketch for you, but I must risk being a mixture of risqué and ridiculous if I’m going to talk about what the poem does with language and imagery. Here’s a link to the complete text of Swinburne’s poem that I used for today so you can follow along as I go through the sonnet line by line.

- Classic mechanical clocks of that era might strike to mark the hours of nighttime. They don’t stroke. Make of this what you will.

- The lover, or perhaps some dream, imagining, or otherwise non-corporeal manifestation of them arrives at the poet’s bed.

- Flowers are invoked. Georgia O’Keefe, Judy Chicago, and Cardi B have yet to be born. Details in Swinburne’s imagery sometimes seem contradictory in a way I find hard to read. Something “pale as the duskiest lilly’s leaf” is hermetic. Is what is being viewed pale or dark?

- Erotic nibbling, or call for Van Helsing? You decide.

- Skin. Bare skin. Victorians are getting hot and bothered now. A lot of care in trying to describe the skin’s tone that just confused me. Wan (pale again) yet…

- “Without white or red.” Is Swinburne color blind? Is this night-vision gray? Even readers who are POC are getting confused here. One reading informed by those bestiality rumors: cephalopods. Students who find this post later: don’t put this in your essay, it will not help your grade.

- Well, the lover appears to be female, and she’s going to be allowed to speak. Thanks patriarchy!

- She speaks like a veddy veddy proper lady too — but apparently interested in “Delight.” Is that what the kids are calling it now?

- “Her face” is honey. Good, let’s keep this PG.

- Her body is “pasture” which borders on Surrealist de-humanizing imagery, though by implication this may be portraying the poet as a horny ruminant — so equality! If then: several stomachs. He can go all night.

- English poets love the word lithe. I’m not sure why, other than to prove they can enunciate without lisping. I don’t think Victorian English winter heating systems were well-ranked, and even in modern Minnesota we have our own personal erotic frissons with hands far from warm. Anyway, in Swinburne’s poem, the hands are “hotter than fire.” Let’s hope the beloved wasn’t chopping jalapenos in the kitchen before coming to bed.

- “Quivering flanks.” Good, someone’s having fun. “Hair smelling of the south.” In the mid-19th century Swinburne was living with William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti in a house in Chelsea just north of the Thames. Luckily for poetic romance, this was a few years after this smell that would have come from the south.

- Feet. Thighs. More skin. Swinburne may have had trouble describing it, but he knows it’s sexy.

- “Glittering eyelids of my soul’s desire.” The arrival of Mark Bolan is prophesized by Mr. Swinburne. Get it on! Bang a gong. Get it on!

The poem’s title may be an indication this is a dream or imagining. Those on the material plane could suggest it’s a report of the great lover Swinburne, post quivering flanks.

Now, can singing help this text out? That’s plausible, as song lyrics can escape close examination and play to Swinburne’s strengths in meter and rhyme.**** And absurdity and mutual laughter are not enemies of eroticism. I give you a testimonial, available with a player gadget below for some of you, or where that’s not seen, this highlighted hyperlink which will open a player in a new tab window so you can hear my performance of “Love and Sleep.” A couple rough spots for the acoustic guitar track I had to throw down quickly, but I love the C# minor11 chord I throw in at the end, even if I don’t know what color its skin is.

.

*By the 20th century Americans were much more straightforward with their name-branding. “Robert Frost” is the best name for that poet of New England’s cool stoicism. Ironic, what with the Anti-Semitism, but then what’s a better name for the poetic force that sought to revive the freshness of poetry’s texts, carefully weighing his words, than Ezra Pound. And for someone who would grow up to like the most honest poetry of the New York School, I can thank my family for Frank Hudson.

**As late as The Sixties, the anarchist and sex-very-positive musical group The Fugs would perform a Swinburne poem just as they would perform Ginsberg and Charles Olson. Not suitable for the easily, or even not so easily, offended, The Fugs usually skipped the euphemism in their name, and as far as looseness in performance and vocal perfection they could make The Replacements sound like The Captain and Tennille. Don’t blame them, but they were a big influence on Dave and myself forming a band.

***Once again, I have to thank the Fourteen Lines blog for bringing this poem to my attention. This summer he’s had me look again at Joyce Kilmer, and now Swinburne. Well worth reading and following if you are interested in shorter poetry forms and expression. Like this project, Fourteen Lines doesn’t limit what they present to the poets they like the most.

****After all, pace Mr. Bolan: what the heck is “I’m just a Jeepster for your love” mean anyway? Did it seem exotic Americana to Marc? Just easier to scan than “I’m a Humbler Super Snipe for your love?” Perhaps, just as Paul Éluard would have it, the beloved makes you “Speak without having a thing to say.”