I suspect a majority of my readers are looking for something related to poetry when they visit here. Stats show continued high visit counts for older posts on some poems this winter, proof of Pound’s dictum that “Poetry is news that stays news.” I remain a little puzzled by the trailing interest in the audio pieces that accompany nearly all the blog posts. The analyst in me assigns that to the fleeting visits of many internet users who sometimes can’t politely play audio, or who don’t care to expend the 2 to 5 minutes most of my musical pieces would take. Maybe some think the audio player gadget will launch an all-to-typical one-hour-plus podcast with an inefficient, in-joking set of hosts rattling each-other’s funny bones? Or it could be musical tastes that diverge, including expectations of better or different musicianship and a more attractive and commercial voice than mine? If so, fair enough.

I doubt any but a few are here for politics. And this week, more so.

I had a political life, I retain an interest in politics in old age, yet even I am on a political news diet this winter.* If it looks like I’ve been writing thinly veiled political posts lately, I’ll claim my intent is more to expiate my own emotions — and to, with whatever value, to succor those that William Carlos Williams portrayed last time as “huddled together brooding our fate.”

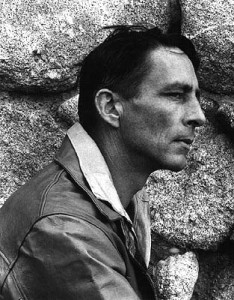

One of my early poetic heroes, Carl Sandburg, had both a political and literary life. I recall a story that as his early Modernist poetry was breaking out into publication, he was challenged on controversial political elements in his poems. He claimed (earnestly, or with care for his emergent career, I don’t know) that any such was incidental — that he, the author couldn’t fully compartmentalize himself. I have no career. My primary interests here are to promote other people’s poetry and to learn and enjoy myself while doing that, and so I’ll make a similar claim.

Which brings me back, as this Project often does, to Emily Dickinson. There are some things exceedingly modern about this mid-19th century American poet: the compression of her language, her freedom from lockstep prosody or conventional syntax, the explicit use of the mind’s interior as a landscape, her abrupt linkage of the prosaic ordinary and the most high-flown concepts. With all that stuff that still seems modern, folks looking to more deeply comprehend her work may need to be reminded that she is, for all her genius, a citizen of a particular place and era.

I remember a short session I had while at the Dickinson Homestead Museum some years back, when a tour docent made a comment that Dickinson wrote a good deal about the Civil War.

“Huh?” I said to myself. I could recall no such poems. In my ignorance then I assumed Dickinson was largely insulated from that, being in small-town New England, privileged, white, and female. I’ve learned a lot since then, and that’s been one of the joys of this Project.

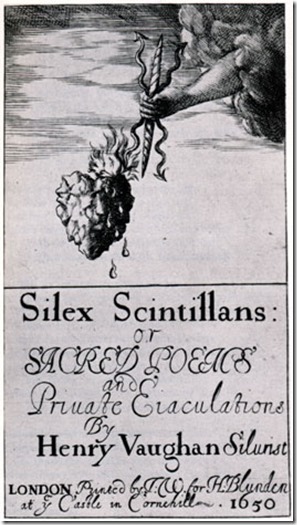

Today’s musical piece is her poem “Inconceivably Solemn.” In its abrupt/oblique language, landscaped with the blank horizons of those em-dashes, I can’t catch a definitive picture of what she’s observing. Metaphoric or actual, it seems to be a parade or celebration. What’s the occasion? An Independence Day? A group of newly mustered troops for that Civil War? An election? I lean to the latter two, and remind those who aren’t steeped in mid-19th century American history that those two things were linked as chattel slavery was a huge and sundering political issue for decades before breaking into war. I first thought the poem was troops going off to war from her town, and it still may be. The 1861-65 war overlapped Dickinson’s most productive years as a poet, and her Amherst sent troops which quite likely enlisted and marched out from the town.

If you’re tired of politics, poet Emily Dickinson seems skeptical of the celebration here.

.

On the other hand, the poem also seems at times to place the celebration/parade as being far away. Is she imagining the soldiers marching into battles at the battlefields that weren’t near her town? Or reacting to battlefield reports in publications perhaps with “mute” engravings of the troops? The poem starts and ends with clear oxymorons, with that first line’s “inconceivably solemn” that is used as the title stand-in. That “solemn” is soon “gay.” And the penultimate line has “wincing with delight.” So then: portraying great causes, assumed honor and bravery, but also suffering and death.

Allow me one moment of my pedantry, and some very uncertain speculation on my part, regarding something that only occurred to me today after working with the poem earlier this winter to prepare the music you can hear below. You see, there’s this odd line “Pierce — by the vary Press.” Dickinson is no stranger to choosing an unusual word, and that may be all “Pierce” is meant to do here.

But one of my youthful enthusiasms was history, and just today I thought, “Is she punning on Franklin Pierce?” OK, I know I’m defeating audience expectations here to ask you to be interested in poetry and vaguely-indie-folk-rock in one Project — and now there’s a history pop quiz? You see, Franklin Pierce was one of America’s worst and least-successful Presidents. He was a Democrat, though in an era where political alignments under that party differed greatly from today. He was elected President in 1852. Dickinson would have been just in her majority, though as a woman, unable to vote — but her father, Edward, was politically involved.** In the 1830s and 40s Edward served six years in various offices as a state legislator and elsewhere with the state Governor. In 1852, the same year that Pierce was elected, Edward Dickinson was elected to the national House of Representatives. Edward Dickinson was a staunch Whig party man. Once more I’ll skip the complex details of the political alignments of this time —but during the 1850s and the run up to the Civil War the Whig party disintegrated. And Pierce? By the midterm elections of 1854 Pierce’s Democratic party was reeling as well. In 1856 Pierce became the first American President to seek and be denied the nomination for a second term — but as ineffective as he was a President, his victory in 1852 coincided with the steep decline of the Whig party of Dickinson’s father.

So from that plausible wordplay connection,*** and the absence of any armaments or uniforms in this poem — only flags, drums, and pageantry — I’m open to the thought that it’s one of those raucous political parades that were a big part of 19th century American politicking that’s being depicted. Improbable gay solemnity could describe such a civic event, and the poem’s side-eye to all the noise and celebration would be all the more appropriate if the Dickinson family’s party might have been on the loosing end of the campaign hurly-burly. If written with hindsight after the Civil War has broken out following the failures of Pierce and his successor, the similarly one term and terrible President Buchanan — then the final “Drums” is reminding us in conclusion that the martial drums of a Civil War were “too near.”

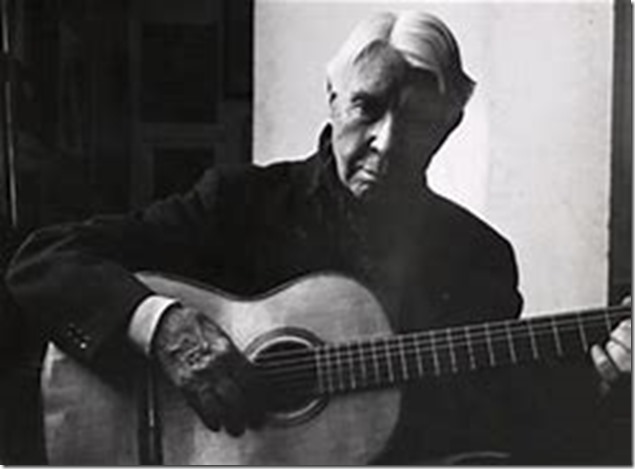

OK, here’s that short musical piece. Perhaps thinking of Colin Mansfield reminding me of the early Woody Allen gag about the cellist in the marching band, I didn’t do a brass band for this, but acoustic guitar, organ, violin, and yes, cello in this song of a parade. There’s a graphical audio player below, but if you don’t see it’s mute pomp and pleading pageantry, I supply this highlighted link that will open its own tab with an audio player.

.

*And Parlando contributor Dave Moore has, at least as of the time being, dropped his monthly comic published elsewhere, which often commented on political issues. He and his partner should be allowed to tell their own story, but he told me recently that he couldn’t bear to do the same comics over again as the country enters its Restoration era.

**I’ve written often here about a theory I have, that Emily picked up information, terminology, and concepts from the family business, lawyering, practiced by her grandfather, father, brother, and maybe even her later-life flame Judge Lord. I’m sure there has been, or should be, some scholar who’ll do a graduate thesis on the use of the Law in her verse. And why not the same regarding the closely allied field of politics?

***Wikipedia says that the Democrats needled the Whigs by campaigning in Pierce’s 1852 race with the slogan “We Polked (successful Presidential campaigner James Polk) in forty-four. We’ll Pierce in fifty-two.”