I mentioned earlier this month that my late wife took creative writing classes with poet Phillip Dacey in the mid-1970s. Later, through her, I met Phil and was able to talk to him a bit about poetry. Phil was generous about this, and I’ve never forgotten that.

It’s always hard to accurately, objectively, analyze where one is in in their writing craft. I knew I was only partway in craft, but I self-judged myself as better than average in the imagination aspect. Looking back at that young man I was then, I’d re-set my judgement now to say I was even less far along in craft than I thought, but I still think my imagination was as good or better than many. Those models that I looked to back then: Blake, Keats, Sandburg, Stevens, and the Surrealists were good enough for starters.

Of course, old men can be wrong when looking at themselves too – presently or retrospectively. I’ve come to consider self-judgment as so unreliable that I treat it as a traveler’s tale: something to listen to, but with a duty of skepticism. If I get time, I might extend this informal series engendered by finding old 1970’s manuscripts packed away in boxes with a few of my youthful poems. If I do, I’ll try to make it worthwhile for you rather than self-indulgence.

This Project takes author’s rights into strong consideration, and you may notice that we almost always perform works in the Public Domain.* As the Parlando Project was starting I learned that Phil Dacey had died. I hadn’t seen him in over a decade at that point, but I contacted his website on hearing the news, and got permission from one of his sons to perform a couple of his poems here. This autumn, while in a dusty boxes clean-out, I came upon a letter from Phil to my late wife dated November 1977, and within the handwritten letter was a typed copy of a poem of his about this time of year.** I felt I had to perform it for you. Phil’s personal site is no more, and I retain no contact info for the family, but this not just a non-profit – non-revenue – Project would propose that the promotional/educational aspect far outweighs any abrogation of the rights holders. If one wants to seek out and read any of Phillip Dacey’s poetry collections, you’d be following my recommendation. I don’t know if today’s poem made it into a collection (I only have some of Dacey’s many books), but you will find poems like this in them.

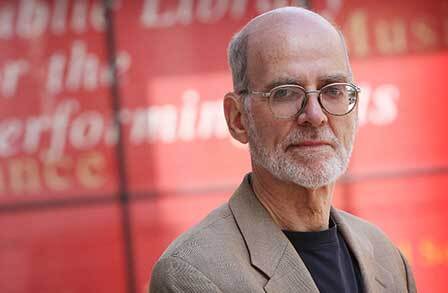

This picture of Dacey is from the poetryfoundation.org site. There are some other poems of his linked to a short bio there.

.

The subject matter of Dacey’s poetry when I met him was spread out between memories of his childhood in St. Louis (a city that punches above its weight in modern American poetry), a Roman Catholic upbringing, erotic desire and its complications, and family and marriage. He came into a long-term teaching gig at a rural Minnesota college, and stayed in the state during his retirement; and as a result, the setting for many of his poems is distinctly Midwestern. In my early posts here where I wrote about Phil’s poetry, I stressed the humor in it and the unusually engaging way he presented his work to audiences. Both of those things might endear him to listeners and readers, but I fear they might blind the completely earnest (or the envious) to other strengths in his poetry.*** I don’t know how he taught the craft professorially, but he models for young writers a subtle kind of poetry, and the piece I perform today is an example of that strength.

“Frost Warnings” begins – and with only casual attention might remain – an occasional poem about the present point in an Upper Midwest autumn. Afternoons remain warm, yet the hours before dawn drop lower and lower until they eventually sink below 0 degrees Centigrade – frost and freezing time for plants. Food gardeners must make their household harvests, flower gardeners, preserve their late bloomers. The poem’s bed sheets with rips and out-worn baby blankets start as reportorial items in a task to stave off frost-burn, but are, if we think again, stealthy deep images of desire and parenthood, the kisses from which we make mankind as Éluard had it our last post.

Then a third of the way in we meet the bedding again, cast as shabby Halloween ghosts. Dacey’s unshowy poetic compression of the worn-life of young parents “too much revelry and worry” is masterful, but might you overlook it on first reading? The modesty of how Dacey uses his craft pleases me – and then he playfully indulges himself by breaking into Wallace-Stevens-voice for the word-a-day-calendar delight of writing down the ridiculous sounding “tatterdemalion.”

On the page it’s also easy to miss the use of rhyme and near-rhyme in this poem: that “revelry” with “worry,” “find” and “vine,” and the comic “jalopy” and “credulity.” Finally, the poem sticks the ending with a rhyme: “Fall” and “mortal.” For at least a while, I think Dacey was associated with “New Formalism” in poetry. “Frost Warnings” is Formalism unfettered.

I wish I’d spent more time on the music I made for this one. It’s been a busy week or so for me, getting vaccinations, some banking business, attending a large gathering against cruel and capricious authoritarianism, getting my own “garden” of bicycles and composing/recording equipment ready for the upcoming winter. As a result, the music I performed with Phil Dacey’s poem is quite short, and is just a trio. I wanted to add a melody instrument, and strip back or deemphasize the piano part for a guitar, or even a horn or wind instrument part, but that would delay things, and I have a half-a-dozen other pieces in WIP state that also want completion.

Phil was a great performer of his own work. He’d have done a great job presenting this, so I tried to use my memories of him to guide me. I attempted to memorize the poem for the performance (Phil often did poetry readings without “reading”) and I hope I brought out some of the elements in my recording that a quick reader of the page poem might miss. So, it’s done, and you can hear Phillip Dacey’s “Frost Warnings” with the audio player below. Worried that someone’s taken the audio player away and spread it over last roses in the garden? Don’t wilt, I’ll provide this alternative: a highlighted link that will open a new tab with its own audio player.

.

*Yes, I have bent the rules a few times – and as the Project was beginning, I thought I’d get permission to use more recent poems by sending simple requests, only to find that would too often require prodigious effort and persistence.

**Here my late wife and Dacey were operating like 19th century Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson well into the 1970s. By the end of the 20th century it’d be emails, and by now, social media or chat software. My dusty boxes and my late wife’s metal box held things for near 50 years, but who knows at what interval current inter-author correspondence-in-effect goes all Library of Alexandria.

***Often humor has a shorter shelf-life and lower canonical trajectory in literature. Using humor, or other approaches which seem to attract a wider audience, can attract a distrust of “mere entertainment.” The argument here, to be fair to detractors, is that such an audience is shallower even if broader, and that “fan-service” audience-pleasers keep an artist from growing and dealing with difficult subjects. My personal belief? Those most difficult subjects are absurd, incongruous, impossible mysteries and dichotomies to solve, and that humor can portray them as well as any other mode.

Phil read a few times with musical backing, as I present him today. One performance I attended was with his sons’ alt-rock band. His “readings,” even if acapella, could have performance elements. He’d weave well-told stories into the poems in such a way that you didn’t always know when the poem had started and explanatory introductory material had ended. He sometimes sang lines when he quoted a song inside a poem. Again, let me concede this sort of thing can be cloying. I’ve heard poetry readers down-rated for an “AmDram (amateur drama) style of presentation, and the “You are hereby sentenced to attend my one-man-show” jokes are easy to make – and that’s sometimes justified. My summary? This can be done badly. Just about all ways of presenting poetry can be done badly. I thought Phil did it well. Other than talent and attention to his craft (including presentation) one reason it may have worked for Phil was the modest and subtle nature of his poetry that awaited and welcomed being presented more expressively than on the silent page. Still, and unlike some performance-oriented poets, Dacey’s poetry does stand up on the silent page – I just have had the pleasure of seeing it in that other framing.