Each April, as part of our celebration of National Poetry Month, the Parlando Project has been presenting in serial form T. S. Eliot’s High Modernist masterpiece “The Waste Land.” This year, we’re up to the third section of the poem “The Fire Sermon,” but before we present new material, I want to give our newer listeners/readers a chance to catch up.

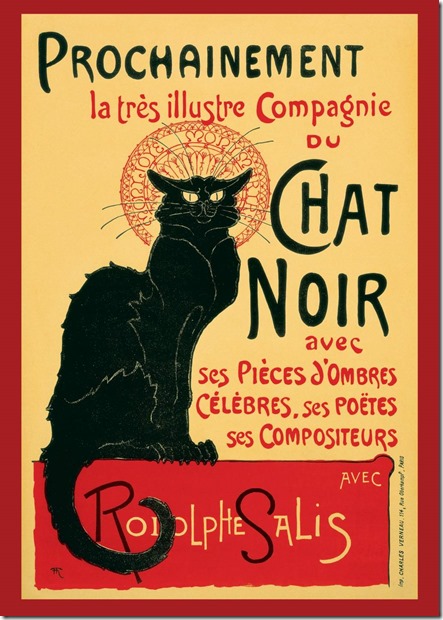

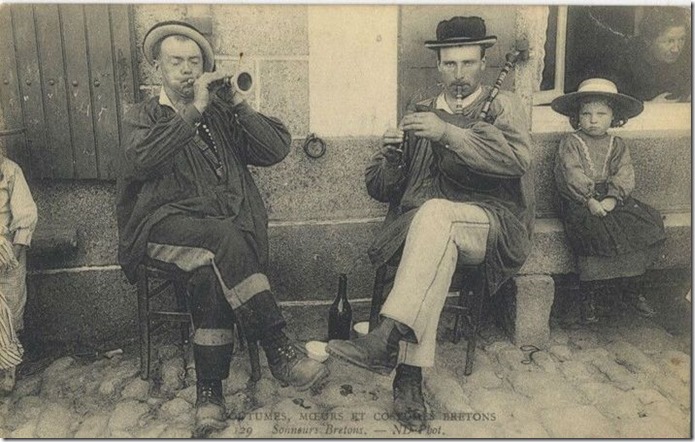

It’s possible to read the entire “Waste Land” aloud as a dramatic monolog in less than 40 minutes total time. Fiona Shaw has done this, and her performances of it cannot be praised or recommended enough. But for me personally (and this goes back to my first readings of the poem) I’ve always been struck by “The Waste Land’s” intense musicality. The collage process of various voices is musical, and “The Waste Land’s” constant changes in tone and insertion of quotes from other poetry eerily predict hip hop mix tapes in a 78 rpm world. Themes emerge and fall back and are then repeated later on, just as they do in long-form musical composition. Eliot even quotes song lyrics multiple times in the poem.

He got $2,000 for service to letters, but our aim is to demonstrate the music in it

So, I’ve long dreamed of performing “The Waste Land” with music—and now, as part of this project I’m realizing that dream on the installment plan. While I think the music can help bring some solace and additional shadings to Eliot’s unstinting look at human failure and limitations, the resulting performance is lengthy. It’s not the kind of thing I can take on creating and performing lightly—and to listen to it, even casually, is not light entertainment either. The Parlando Project normally focuses on shorter poetry, the lyric impulse. Almost all of our pieces are under 5 minutes, and we have hundreds of them available here. So, don’t feel obligated to listen to these longer “Waste Land” pieces. They are not for everybody, and I believe they are consistent with Eliot’s design to write only for those willing to look at dark impulses and feelings, to weigh and consider them within your mind and heart.

Here’s “I. The Burial of the Dead,” the first section that famously opens with “April is the cruellest month, breeding/Lilacs out of the dead land…” which is likely a reason that April is U. S. National Poetry month (and may already be referring to another poem, Walt Whitman’s Lincoln elegy, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.”)

And here’s last year’s contributions, the section “II. A Game of Chess” rolled up into one piece for the first time here. I start out this one by making an ex-post-facto connection of Eliot’s lavish and dissipated opening of “A Game of Chess” with the late-night, dragged out, “Ain’t it just like the night” style of Blonde on Blonde era Bob Dylan, and it ends with an appearance of a guest reader Heidi Randen for the monolog about Lil and Albert and their just-discharged-from-the war marriage.

This month we’ll continue our serial presentation of “The Waste Land” with one of its longest sections, “III. The Fire Sermon.” If you’d like to read along with the text of the poem while listening, the full poem is here. With these musical presentations I maintain that you can listen to them and not feel that you need to understand what the poem means in the essay-question sense, and instead only require the poem’s words to strike you with scattered connotations and impacts. There are a great many resources for those who would like to delve into deeper meanings of “The Waste Land,” all the things that Eliot intended to put there—and also the things he only inherently and accidentally included. For those that enjoy that, there’s much there at that level, but I remind you of the concept I laid down a couple of posts back regarding Emily Dickinson’s much shorter poem: a poem isn’t so much about ideas, it’s about the experience of ideas.