We seem to be in a month of sky omens in the Midwest, with the Perseids meteor shower and a solar eclipse following one after the other. Perhaps because solar eclipses are rare, poems about them are rare too. I’m going to cheat then, and present two pieces about lunar eclipses, a slightly more common event that occurs when the Earth comes between the Moon and the Sun, blocking the moon‘s reflected shine.

I’ll lead off with one written sometime in the 19th Century: Thomas Hardy’s sonnet “At the Lunar Eclipse.” I remember the moon-trip photos, taken near the middle of the 20th Century, looking back at Earth, where for the first time, we could see our planet whole. Hardy reminds us, a hundred years before that, that we could see our whole Earth in a shadow play during the lunar eclipse.

For the first time we could see the big blue marble

…also, composting toilets!

Optimists at the end of the 1960s thought these whole Earth pictures would help us understand our solitary yet majestic unity and common cause. Hardy, though he had only the Earth’s shadow during an eclipse to work with, is not so sure.

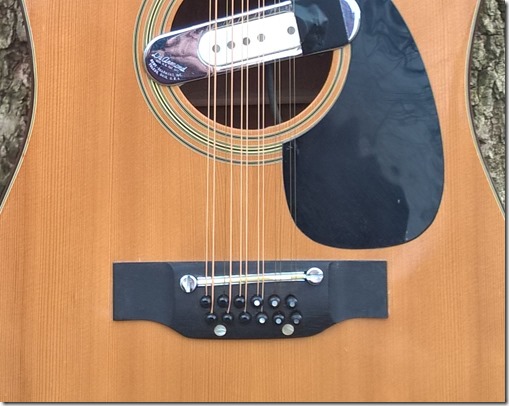

The LYL Band’s performance of this Hardy poem is a live recording from a few years back and it strains to reach “bootleg tape” recording quality, but still I hope it retains some vitality. And since this Hardy poem is referenced in the next piece, I’m going to give this rougher recording an airing.

Though neither I or the Parlando Project had anything to do with it, if you’d like to hear a restrained and lovely simple solo voice and piano sung setting of the same Hardy poem, you can view it here. To hear the LYL Band performing our louder version of Hardy’s “At the Lunar Eclipse” use the player just below this.

My own lunar eclipse piece is set in our century, and in my Midwestern place. I start off by musing on the same planetary shadow play that Hardy wrote of, but wondering if we were our planet, might we make sport of our standing between the sun and moon, as we did as children when the film strip broke in class, or the slide tray of vacation photos needed to be changed, by making hand shadow puppets in the light. Then, as the blood moon eclipse neared totality, and the dark was dark, save for the streetlight at the end of the block and a houselight here and there left on, every hand up and down the street raised itself to the heavens, holding their lit smartphones, as they took pictures of the moon blocked by ourselves on our planet.

A blood moon eclipse. “Can immense mortality but throw so small a shade?”

Unlike our last pairing, the perennial face off between Marlowe’s Shepherd and Raleigh’s Nymph’s reply, my poem “Lunar Eclipse – The Earth in Transit between the Moon and Sun” isn’t really an “answer song” or a diss on Hardy. In a lot of ways I wanted more to simply update the scenery of Hardy’s poem. Oh, and that title is awkward, but enough listeners didn’t know the mechanics of a lunar eclipse, that we are in the middle on the earth blocking the Moon from the Sun.

What did I mean by the last line? Well, as I sometimes do, I wanted to mean several things. I wanted to say we thought we could capture this cosmic event that had stopped our routine in with the birthday pictures on our smartphone camera roll. I wanted to say, as Hardy did, that we are seeing the whole of our planet, the lives of all our neighborhoods, yet it is only one disk in the wide sky. I wanted to say that our present, particular lives: all our details, our family, our neighborhoods, our homes—though they are the way we experience living—are but one transit of life. Maybe I wanted to say something else that even I wasn’t sure how to say? If so, I wouldn’t know. Sometimes that happens in poems.

Again, we have the LYL Band performing this piece, but it has better recording quality. To hear it, use this player just below.