Are you familiar with the song “Reynardine?” You might be. It’s been performed by many of the best performers in the modern folk revival: Anne Briggs, Fairport Convention, John Renbourn, June Tabor, Bert Jansch and others.* Today as I extend our Halloween series, I’m going to introduce you to a version of the song you haven’t heard, a version that I’ll maintain uses more efficient and effective methods to convey an air of mystery. There’s supposition that this version may have been an indirect catalyst in the way the song you may know was presented, but this little-known version’s lyrics are so good that singers should consider using them in contemporary performances.

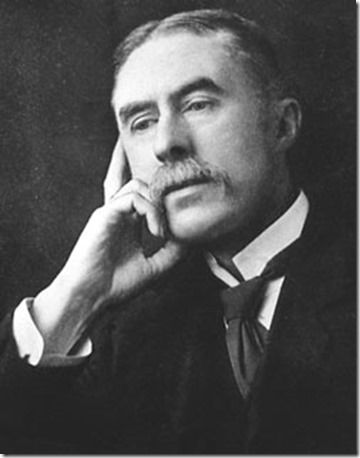

Where did I find this new version of “Reynardine?” In the 1909 book of collected poetry by Irish poet Seosamh MacCathmhaoil (AKA Joseph Campbell) titled The Mountainy Singer.

I’ve spent a day or so in hurried research on this, even though long-time readers (or readers of our last post for that matter) will know that Joseph Campbell** has been of interest to me for a couple of years now. Here’s the shortest version of what I know that I can make.

Songs related to “Reynardine” go back to the early 19th century in the British Isles and the U.S. Wikipedia gives us a representative early (1814) example, and this helpful page gives us a catalog of later 20th century versions. The older versions sometimes vary the name of the title character and contain no supernatural elements. The typical plot is a broadside ballad variation of what is still a staple romance-story trope: a woman meets an erotic stranger who she thinks may be disreputable and possibly stranger/dangerous — but who also may be wealthy or noble (Reynardine claims to have a castle in most versions.) Over several verses there may be Victorian code-words like “kisses” and “fainting,” and the title man may leave the lady wondering where he’s run off to.

Skip forward to the early 20th century: in 1909 (the same year that Campbell as MacCathmhaoil publishes “The Mountainy Singer”) a musicologist Herbert Hughes publishes the first volume in a series of successful song collections titled Irish Country Songs. A great many songs that will be featured in Celtic and general folk-revival recordings, performances, and song anthologies are included in Hughes series of books.*** Hughes’ printed version of “Reynardine” is shorter than most extant versions, a verse and a once-repeated refrain, and it’s even called a “Fragment of Ulster Ballad.” In a footnote at the bottom there is this note, unsupported by any of this song’s lyrics:

In the locality where I obtained this fragment Reynardine is known as the name of a faery that changes into the shape of a fox. -Ed.”

A century-old song, with many collected versions, and this is the first time that “Reynardine” is said to have supernatural elements. Where did Hughes get this? I don’t have a direct link, but there is our version of “Reynardine,” published in the same year by the Ulster-native Campbell who is not credited on Hughes’ score, though Campbell/ MacCathmhaoil is credited in at least two other songs in Hughes’ Irish Country Songs. The supposition is that Campbell is either “the locality” — or that Hughes and Campbell shared a traditional source which has left no extant song version that indicated to both of them that Reynardine is a supernatural creature.

Footnotes! Pretty scary boys and girls! Herbert Hughes’ songbook presentation of Reynardine that likely changed how the song was viewed.

.

Did some of the later 20th century folk revival singers know of this footnote? Possibly. One highly influential revivalist A. L. Lloyd sang a version that included at times a remark that Reynardine had notable teeth which shined. In pre-dental-care England this detail may have been enough supernatural evidence. Furthermore, he wrote of the were-fox context in liner notes more than once 50-70 years ago which led other performers to explain the song that way, either as their own subtext or to audiences.

But here’s another mystery — and I’m saying, a useful one — why isn’t Campbell’s version of “Reynardine” known and sung? Let’s look at it. The chords here are the ones I fingered, though I used Open G tuning and I formed the chords while capoing at the 3rd fret, so it sounds in the key of Bb. But the music “Reynardine” is sung to isn’t harmonically complicated (you could simplify the chords), and a better singer than I could better line out the attractive tune used by myself and most performers. ****

I made one change to Campbell’s masterfully compressed 1909 lyric. I use the more instantly recognizable, less antique word “lover” where Campbell had the easy to mishear “leman.”

.

Poets and lyricists: this is a marvel. No need of footnotes or spoken “this song is about…” intros. The supernatural element is subtly but clearly introduced. The refrained first stanza was as published by Hughes, and is commonly sung in modern versions. The second makes the bold move of changing a folk-song readymade where some damsel’s lips are found to be “red as wine” with an animalistic short-sharp-shock of Reynardine’s “eyes were red as wine.” The third stanza lets us know he can be a fox in form, subject to fox hunters with the brief but specific statements of the horn and hounds. Another subtle thing: Campbell repeats the “sun and dark” all-day-and-all-of-the-night lyrical motif to tell us this isn’t an ordinary fox hunt scheduled for seasonable days befitting rich people’s leisure, but a 24-hour emergency. The hunters know this fox isn’t normal. The refrained first verse reminds us that the lover may know that the were-fox can also take a human form, and make use of human defenses, such as castles, which the assiduous hunters do not.

As a page poem this has the vivid compression that Imagism preached. Compare the efficiency of this story-telling to “La Belle Dame sans Merci” which has its sensuous pleasures, yes, but takes it’s time getting to the point. The two poems convey essentially the same tale, but Campbell can leave us with an equally mysterious effect using so few and aptly chosen words.

There’s a player below for some of you to hear my example of a performance of Joseph Campbell/ Seosamh MacCathmhaoil’s “Reynardine.” Those who don’t see it can use this highlighted hyperlink instead.

Hopefully, I haven’t put any of you off with my own footnotes about this song’s unusual history and transformation. If you skipped to the end, here once more is my message today:

If you perform this sort of material, consider using Campbell’s lyrics instead of those you may have heard from other singers. They’re that good.”

.

*And more recently in a softly lovely version by Isobel Campbell, formerly of Belle and Sebastian.

**Obligatory statement: no, not the Power of Myth guy. I suppose it could be worse, Campbell could have been named James Joyce or Sinead O’Connor, and confused us too.

***Besides “Reynardine,” Vol. 1 includes another popular folk-revival song, erroneously considered to have wholly traditional lyrics: “She Moved Through the Fair” which Hughes’ correctly credits lyrically to Irish poet Padraic Colum.

****I was somewhat working from a very rough memory of Bert Jansch’s version on his Rosemary Lane LP. It’s a good thing I was rushing this and didn’t stop to listen to Jansch — his version is an acoustic guitar tour de force. If you’d like one performance to demonstrate why I, and many acoustic guitarists, revere his playing, that would be a good choice.