This is an elegy, not a love poem, but then an elegy is a love poem that replaces the focus masking the complexity of love with the common mystery of death. Even the images and incidents can have an eerie similarity, as an absence may be at the center of either.

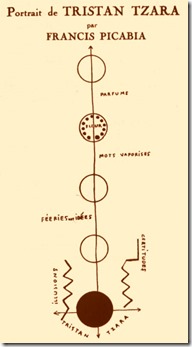

The author of today’s piece, Tristian Tzara, is as much as anyone the founder of Dada—if that absurdist movement can structurally support a founder. Like much of the early 20th Century modernist movement, the horrors and changes of WWI accelerated Dada’s development. Proudly anarchistic and rejecting the whole lot of social norms and artistic traditions, Dada was at turns playful and bitter about a European world order that that was itself disordering everything on the continent though modern warfare.

When I look inside the back of my guitar amp, do I find? Picabia’s portrait of Leo Fender, or a tube socket schematic?

As we’ve learned in earlier posts here, a whole generation was mobilized as part of The Great War. The teenage Tzara, residing in neutral Switzerland, escaped this, but he apparently tried to gain funds from both sides’ propaganda arms to fund Dada activities—which would be just the kind of audacious prank that Dada loved.

The subject of today’s piece, Guillaume Apollinaire, was a slightly older member of that WWI generation who should have gone on to even greater things after the war. As I mentioned last time, he had invented the name for Surrealism, the modernist movement that was a post-war outgrowth of Dada. Before that, he had also invented the term Cubism. In France during this time, Apollinaire seemed to know, and was admired by, everyone: composers, writers, painters, theater artists, the whole lot of this vibrant cultural scene.

Swept up into the military by the war, Apollinaire was seriously wounded at the front and weakened by his wounds, he died during the great flu outbreak of 1918.

Apollinaire, his war-wound bandages “pendaient avec leur couronne”

His death then leads to Tzara’s elegy, today’s piece. Given Tzara and Dada’s reputation, I was worried as I started to translate this. Translation, particularly for someone like me who is not a fluent speaker of other languages, is already fraught with issues, but doubly so with writers who can use arbitrary absurdist phrases intentionally. When is something unclear, and when is it meant to be so? That’s a question you ask a lot with these writers. I have a prejudice for vibrancy, and if I feel there’s a good image or English phrase hidden in an unfamiliar language’s idiom, I will generally seek to bring it out, but I also realize that I’m fully capable of misunderstanding the writer’s intent.

With Tzara’s “The Death of Apollinaire” I grew to believe that this was a sincere elegy for this much-loved artist among artists, and so, translated and performed it as such. Yes, it has its absurd images, but I chose to translate them with clarity in mind. Apollinaire died in November, and so I took the mourning images as a series of late autumn images, and presented them as such. I had the most puzzlement with the line “et les arbres pendaient avec leur couronne” which can be simply left as an unusual combination: a (presumably, shiny metal) crown hanging in a tree-top. As I looked at “couronne” it appears that it’s used also for a laurel wreath crown, and for a funeral wreath too, and for a while thought “wreath” or “funeral wreath” would be the best translation. And then I considered the botanical meaning of “crown” applied to trees, and the follow-up line “unique pleur” made me think of the last leaves in autumn, a rather conventional image—but a great deal of what makes that conventional in English is the popular song “Autumn Leaves” written originally in French by Surrealist Jacques Prévert! My translation: “And the trees, those still with hanging leaves” takes liberties with Tzara’s words, in hopes that I might have divined his image. I’m more confident in how I translated the last line, “un beau long voyage et la vacance illimitée de la chair des structures des os” which I proudly think is superior to other English translations.

Musically, today’s performance is a mix of 12-string guitar in Steve Tibbett’s tuning, with electric guitar and bass. As always, there’s a handy player below so that you can hear it. If you like a piece you hear here, go ahead and hit the like button, but it’s even more important in bringing this work to others attention to share it on your favored social media platform. Thanks for reading and listening, and double thanks for sharing!