Long time readers know that the Parlando Project is largely about our encounters with other people’s words – usually their literary poetry. Poetry, even impersonal or hermetic poetry, is a rich way to transfer experience between consciousnesses. Poetry’s strengths in this transference over memoir, blog post, or informal conversation are largely the strengths of focused beauty – that thing that attracts us even before knowledge, expressed as sound or by novel connections.

Still, these beautiful elements of poetry come with costs, which is why many, most of the time, prefer other modes. Yet, I think the shortness and the compressed incidents of lyric poetry offer a possible compromise. We’re asked to share a little burden, a few minutes of reading or listening, subconsciously absorbing the word-music and linkages, which may in leisure or with mood be extended by re-reading and re-thinking such a small number of lines.

One of the things that caused me to begin this Parlando Project was thinking that a short musical accompaniment might add pleasures to possible serial re-encounters with the words. Is this so? I’m not sure, though I persist in doing this.*

That preamble out of the way, I’m going to look like I’m violating the “Other People’s Stories” maxim that is a principle of this Project, because I’m presenting today words I wrote to go with the music I compose and record – but hold on, I’m going to tell you this is still about a poetic transference across a gap.

Here’s why: once again I’ve been running into things from decades ago as I do my “death cleaning” reduction in things stored away or unlikely to be of foreseeable use. Just last week I moved aside a drum set that had been played by Dean Seal when he was in the LYL Band,** and found under the bass drum a plastic carryall tub with things hurriedly packed up after some gig: a Radio Shack battery-powered mixer, cables, a guitar strap, a cassette recorder, and a few tambourines we’d hand out for audience participation. And more spiral, college-ruled notebooks have come to light. Glancing through one I found a page with 9, untitled, lines – the start of a poem. From the style of the poetry in the fragment I think it’s from the 1990s, but it might be earlier or later. It caught my attention because it seemed to be talking about November in Minnesota in that interval right before the first snows come.

I remember nothing about writing this poem, or what prompted it, but it had some nice word-music and was roughly pentameter. That pentameter made me think I was writing a sonnet, and for some reason left off at this incomplete draft. That night, before bed, with my aching muscles and joints from twisting, bending, and hauling I decided to complete a full 14-line draft.

More musical perversity: the difficulty in finding times to record acoustic guitar with sensitive mics in the past year or so has increased the number pieces I’ve done with that instrument.

.

For the final 5 lines I used an incident from a recent bike ride. Rolling down to a favorite breakfast destination at the borders of my wooded city I’m usually met with a rewarding bit of wildlife (outside of deep winter): constant squirrels, rabbits, small rodents, birds, including waterfowl by a pond and creek I pass, insistent crows, and so forth. If Keats wrote his “Ode to Autumn” on Hampstead Heath in the Highgate section of the city of London, these near-daily rides of mine with this contrasting nature in the midst of modest single-family houses and parkland is my equivalent. What I saw this day was a little epiphany – a squirrel had been quite recently struck down crossing the road. Not smack dab run over, for it was not squashed, and there was only a little blood – yet it was clearly not moving or breathing, and even from the height of my bicycle its eyes could be seen fixed and dead. And then, as I was approaching, carelessly another squirrel scampered out onto the road and up to the corpse. Though I was riding onward, and only slowed a bit moving to the side, this squirrel bent down right to the head of the dead one, close enough to touch it barely with whiskers, clearly looking closely at it, for a moment regardless of my vehicular approach.

And then, just as I was beside them, it scattered off, missing by accident or close design, my slowed, but rolling, bike wheels. What was that squirrel after, what was it thinking in those few seconds with the dead one? This was the matter to finish the poem that had started years ago with a rabbit finding scarcely-leaved autumn bush and brush to hide in. And I too had had my customary Parlando encounter without firm context, working with the part of the poem written by someone I hadn’t seen for decades: though in this case, it was my younger self. Not really that different from the usual encounters here with Frost, Dickinson, Sandburg, Millay, Stevens, Hardy, et al.

I originally gave the resulting sonnet the title “Before the Rapture of Snow,” because I thought that tied-in the rabbit’s anxious waiting and the dead squirrel. I drew back from that thinking it too grand a reach, and because the theological implications of “rapture” would repel, puzzle, or draw in too-determinant reactions.

I was lucky enough to have a Monday to record this, finishing what felt like a good take of the vocals and acoustic guitar just before I had to leave my studio space. I added piano yesterday and mixed the tracks. As a non-pianist I’ve fallen into using that instrument simplistically as I do here, and I’ve grown fond of how these pounded single notes mesh with the timbre of acoustic guitar. You can hear “Before the Snow” with the audio player below. Has the player been raptured up to heaven? No, it’s just that some ways of reading this blog suppress displaying such a thing, so I provide this highlighted link that will open a new tab with its own audio player.

.

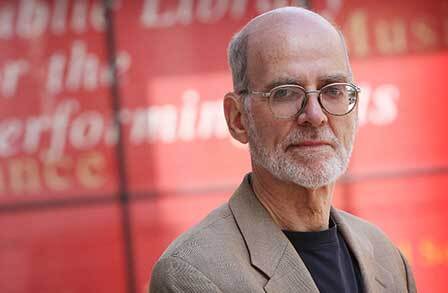

*Besides my lack of talents for promotion, I sometimes feel what I do with this Project presents a number of detriments to gathering an Internet-scale audience. Poetry, as I write above, is not something sought out by modern Americans in great numbers. And then the music I make suffers from these things that reduce audience interest: I’m not a singer with a beautiful voice, nor do I think of myself as a performer with charisma or erotic appeal, and the music I make despite that is both too varied and too limited.

Many potential listeners or readers, presented with an infinite library of options in our modern age, will avoid things that have but one of those strikes against it – and to add another one or two against the Parlando work wouldn’t be rare either.

All this isn’t breast-beating or humble-brag, and I’m even hesitant to waste your time writing this. I am proud of much of the work I’ve done over the last decade here. While my audience is Internet-small, I believe it’s not all that small by poetry standards, and increasingly, not completely outsized by the audience for much non-Pop Indie music. Thanks to my hardy listeners!

**Dean was working elsewhere in comedy, and with at least one other partner in music, when he played in the LYL Band in the 1980s. He was talented and creative, we were looking for a drummer or bass player, and we perversely came upon him as both – unconcerned with the challenges of one person filling both roles! He may have grown to think of us as less professional or ambitious than he was, I don’t know, or events of his life may have intervened, but for reasons unknown to me we just stopped playing together – but this happened without him picking up the small drum set he played with us, and stored at my place. While working on my cleanout this fall I briefly tried to find contact info for Dean to see about the drums, but the trail ran cold after finding articles about him being part of the pastoral lineup at a church that no longer listed him on staff.