Here’s a poem by British poet A. E. Housman that’s not an Easter poem — and then again, might be. On its heathered surface it’s a poem about wildflowers. My wife, who likes to hike in natural areas, could probably make good sense of it on first reading — but if you don’t know your wildflowers and aren’t attune to some Britishisms, you might be left with just a pretty set of words.

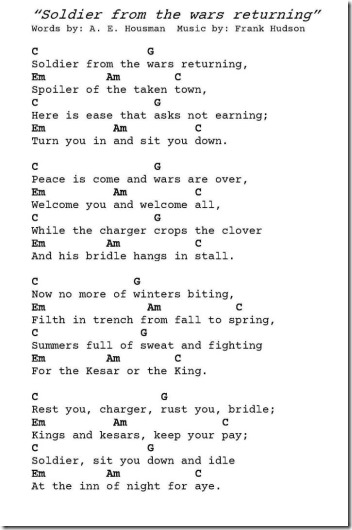

Trying to mesh Housman’s poem to the music I was forming, I ended up making changes to the poem as it appears on the page (linked here).

.

Right off in the poem we’re rambling on “brakes.” As a bicyclist, “hilly brakes” might make me think of brakes squealing on my old much-missed mountain bike. While I’d like to think of Housman in a tweed jacket enjoying such a ride, the “brakes” here are a Britishism for a thicket or area of shrubs and other undergrowth. Other words that would have “special” British or archaic English meanings? Young girls are asked to “sally” — which is not the given name of one of the girls, but a word meaning to go forth. In the first stanza besides the “brakes” Housman calls the place of the flowers “hollow ground,” a word-choice that’s a little harder to parse. Hollows are an old word for a small valley, which is likely what Housman means (he calls out valleys in the last stanza). One reading I came upon thought the “hollow” a variant of “hallow,” as in “hallowed ground,” and derives from that the idea that Housman’s wildflowers have sprouted in a graveyard. I can’t find a cite for that variation, but hollow is a somewhat odd choice here, and without regard for hollow meaning hallow, graves do produce hollows in the ground.

Our first wildflower, primroses, are found in that opening stanza. Next stanza, next wildflower, the windflower, which I first thought was a Gerard-Manley-Hopkins-like compound word, but windflower is the common name for another wildflower. The stanza goes on to introduce the flower featured in the poem’s title: The Lenten Lily which the poem tells us “dies on Easter day.”

Third stanza, the primrose and windflower are still present to decorate May Day, but the daffodil we’re told is not. And the poem ends with a final stanza telling us again that the daffodil dies on Easter day.*

Here’s more wildflower ignorance on my part: the Lent or Lenten lily is the daffodil — just another name for the same flower. I’d never heard that Lent lily name, but for a long time I really didn’t know the daffodil either. The daffodil is a common wildflower, but unlike my wife, I don’t know it to call it out by its name and properties on sight. I knew the daffodil not from the book of nature, but from the famous poem by William Wordsworth** “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud.”

A few years ago while visiting England in the early Spring I came upon an entire lawn at Kew Gardens filled with yellow flowers. “Daffodils” my wife told me. This was a London park, not the hilly brakes of Britain’s Lake District, but I suddenly found myself, from her knowledge imparted to me, inside Wordsworth’s poem and the physical, now knowing, presence of this flower. The dark green grass and the sunny yellows in array before me were ever brighter because back at my home in one of the most northern states, things were still snow covered in early April.

My view soon after entering Kew Gardens.

.

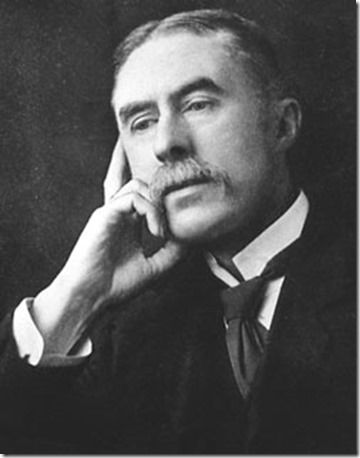

Housman is telling us something else about the daffodil: not only is it one of the earliest blooming Spring wildflowers, giving rise to the Lenten lily alternative name for it, but it’s also one of the quickest flowers to die and disappear. That name, that property, gets us to the question of “Is this an Easter poem?” Housman is not at all a Christian devotional poet — he was a devoted academic classics scholar and agnostic.

Well, maybe that’s his point. Easter is the particularly Christian holiday of resurrection and eternal life. Housman, not a Christian believer, has written a poem that refrains on something natural — this flower — that’s not spiritual like a soul or godhead, but a piece of lovely, wind-caressed carbon that dies by Easter Day. In that natural order, this brief wildflower certainly dies. A Christian apologist could easily counter: that’s the promise of The Resurrection, that it is something else. One can read the poem and see either side. Of course, there is a thumb on the balance: Housman has written a poem, and I’ve gone along with him and made a song of it. Poems are not so much about what they say — because they have sound and a carefully selected order, they are more about what it feels to say or see or sense something.

You can hear what I made of what Housman’s poem portrays with the audio player you should see below. What, has any player disappeared like the daffodil? It’s not that — some ways of reading this blog don’t believe in showing the player. So, you can roll away the stone and use this highlighted link to hear it instead.

.

*I’ve read that English churches are decorated with picked daffodil flowers during Eastertide, which may be what Housman is referring to when he says that other Spring flowers survive April. Or the primrose and windflower et al may just be hardier species.

**As it turns out, William Wordsworth based his daffodil poem partly on journaling done by his sister Dorothy Wordsworth who had accompanied him on his Lake District walks. That’s a wonderful thing about our relationships with others: what we see and sense can be informed by them.