I live in a city where 12-string guitars are over-represented. Since I’ve only lived in Minneapolis for 50 years, I can’t say for sure why that’s so. Folk-revival pioneers Leadbelly and Pete Seeger, likely the ur-source for the instruments post WWII use, have no direct connection, but by The Sixties™ this powerful but awkward branch of the guitar family had a nexus of players here. The guitar playing other two sides of the Pythagorean Koerner, Ray, and Glover trio played 12-string. Leo Kottke made the beast a virtuoso instrument while working the small clubs and coffeehouses of the Twin Cities. John Denver had fallen in love with a Minnesota girl and played a lot of 12-string (and who can say what is the cause and effect there). By the time I arrived in the Seventies, Ann Reed, Peter Lang, and Papa John Kolstad also played 12-string in small venues. The year my ten-year-old Pontiac rolled into town, a local college student, Steve Tibbetts, was self-recording his first LP featuring 12-string landscapes pebbled with percussion over which roamed howling electric guitar wolves.

At that point I owned my J C Penny’s nylon string guitar and a weird amorphously shaped Japanese electric guitar I’d bought at a flea market and for which I couldn’t yet afford an amp. Accommodating my new hometown, I soon felt I should get a 12-string guitar. A year or so after arriving I managed to afford a Cortez 12-string acoustic which was sold as a sideline item at the local Musicland record store. My memory was it cost $79. Designed to outwardly look like a “professional” instrument at the lowest cost, it could have been the music equivalent of costume jewelry or a stage prop. As these sorts of things go it wasn’t as bad sounding as modern forum-dwelling guitar aficionados would suspect, and mine had pretty good “action,” reasonable string height to allow easier fretting.

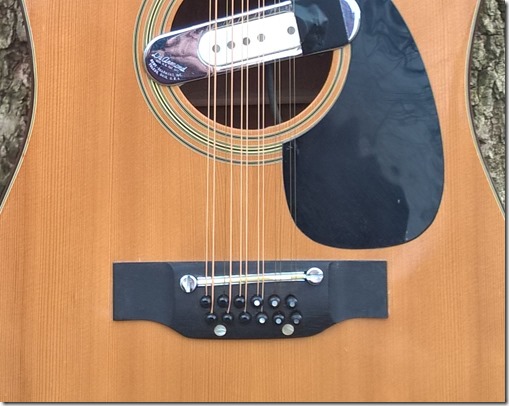

Later in the Seventies I added a DeArmond sound-hole pickup and I played this guitar with the LYL Band, and for the rest of the 20th century. With their double sets of strings, 12-strings sometimes warp and self-destruct under the increased string tension – but cheap and cheerful as the Cortez was, it’s held up, though the top has bellied-up over the years.

I eventually got a better 12-string, but I kept the Cortez around. A few years back I set it up to use Steve Tibbetts stringing variation where most of the octave strings are replaced with unison strings.*

Now let’s jump the month just ending, January 2026. As a writer I can’t paper over the immense mood shift this entails: from oddities about the types of guitars, to lives being mangled by intended government action.

I still feel unable to write fully about my reactions to the many injustices and atrocities that are incurring at the hands of thousands of federal agents that are roaming my city and the rest of Minnesota this winter. The first of the murders this month, the shooting of Renee Good in front of her wife happened on the street just across the alley of my home office and “Studio B.” If I hadn’t been wearing headphones and working on music for this Project I would have heard the gunshots – instead, it was my wife who rushed in to tell me. As of the end of the month, we’ve had a non-fatal shooting and one more murder by the federal agents, and a daily grind of sufferings. I won’t be the one to try to catalog all the careless to cruel things that are happening day after day. It sorrows me, and perhaps you, and at least for now, this information is available elsewhere. Nor will I offer enough praise for the ordinary people in this city who are trying to mitigate that suffering and plead for its ending. I will call out one thing many of them are doing: they’re seeking to be “Observers,” the term that has come to be used for folks who feel called to witness and record with their phones what our own government agents are doing to the people living around us. Think about this for a moment as you read this: these Observers are intending to go to where cruel things are being done by armed bullies who will use their weapons – issued along with pledges from their leadership that they will face no consequences – to rough up, to detain with and without charges, to attack with chemical and “less-lethal” munitions, to in two infamous cases, to kill them. Folks were doing this before Renee Good was killed – and after she was shot, more signed up. After the next murder of Alex Pretti pushed to the ground holding his cell phone camera: more again signed up.

I think of the incredible bravery of the American Civil Rights movement of the mid-20th century, and this is like unto that. But here’s something else I think concerning that role, something I don’t recall being written much about yet. There’s a chance that these observers are going to see armed agents of our government kill someone in front of them, and they’ll be tasked with recording that. The infamous murders of the Sixties’ Civil Rights movement happened in darkness and rural separation, though the corporal brutality of clubs, dogs, and firehoses was done in public and was sometimes filmed.

Along with bravery, that’s an additional heavy burden to take on. And some are now carrying that specific burden. We have memorials to Alex Pretti and Renee Good, but I want to stop and think of those that witnessed their killings, and what they must be carrying in their minds. My mind is once removed, however close to me these things happened, and yet it’s filled with conflicting and intense reactions – but they were there, in that instant as this happened. Dozens of people in my city, some intentional observers, some protesters, some just bystanders, are carrying that as I write this.

So, the name that most often arises in my heart this month after the many insults to justice and mercy isn’t one of the detained or murdered, but is instead, Rebecca Good, Renee Good’s spouse, who was apparently observing ICE action on the broad avenue near her house and mine. When the federal agents came up to their car and began to hassle Renee, Rebecca tries to draw their attention away from her partner. In that moment, I read her actions as saying: detain me, let Renee get away, throw me down onto the ice and snow and get a few punches or sprays of mace into the eyes while you strap cuffs on me. Rebecca can’t get in as Renee puts the car in drive, the doors are locked. On one of the videos you can hear her say “Drive babe,” allowing herself to be left behind with the agents. And then the shots.

You hear her voice in another video, moments later, sitting on the side of that broad road just behind my house, saying that they’ve killed her spouse, and moaning that she was the one that suggested they move to Minneapolis. I should transcribe her exact words, but I can’t bear to watch that video again just for journalist precision tonight.

Another jarring transition I can’t engineer now. In between Renee Good’s murder and Alex Pretti’s, and thinking of Rebecca and other survivors, and of the witnesses, observers, I somehow fell to thinking of a song written by another 12-string guitar player of The Sixties,™ Fred Neil, “The Dolphins.” Neil’s songwriting was a mixture of earnest and off-hand, an unusual combination. “The Dolphins” is a somber wail about the cruelty of the world compared to the swimming pods of the famously playful aquatic mammals, and it’s just a handful of words.** Neil’s career was one of those “better known to other musicians” ones, and his song was covered by others back then, particularly those who played the 12-string guitar. Now if we move onto the Seventies – that off-brand extension of The Sixties™ – I’ve always thought that when another songwriter who played a lot of 12-string guitar in The Sixties, David Bowie, had to have been thinking of Neil’s song when, in the midst of his Cold-War-Berlin masterpiece “Heroes,” he has one of the lovers kissing next to the armed guards around that inland city’s border wall think of dolphins again.

Fred Neil had a rich baritone voice, and David Bowie was a talented singer. I, alas, am mostly singing things here myself, yet I wanted to make a realization of those two songs while thinking of Rebecca Good, and others I didn’t (and still don’t) know how to number and name in this time. That would mean no first-rate vocalist, and I also decided to go primitive on the 12-string guitar, using that old Cortez 12-string. As the song progresses I strummed that 50-year-old box loudly, and I didn’t necessarily want a pretty 12-string with a rich sound.

.

*One of the features of the Cortez is a “zero-fret,” a still unusual feature that brings two benefits: it insures optimum string height in the “cowboy chord” first position area for easy playing and allows greater freedom in using different gauge strings at the player’s whim. Conventional 12-strings use a thinner string tuned an octave above the regular string for the low E, A, D, and G strings. Steve Tibbetts (like Leadbelly) instead uses two regular gauge, unison not octave tuned, strings for some of the courses. My Cortez 12-string has unison D and G strings.

**Neil’s choice of the dolphins, however casual it seems in his song, was a serious one. He drifted out of the music business in the Seventies and spent the rest of his life working on a dolphin support/conservation project.