I enjoy the part of this Project that gives me cause to examine the lesser-known and forgotten poets and poems. Even the most famous literary poetry principally exists in quiet books, but give me a book now largely unread and my interest is perked.

Today’s poem is by Richard Hovey, one of the co-authors of a remarkable yet forgotten three-book series that began with Songs from Vagabondia published in 1894. Who was Hovey?

He was the son of a Civil War general* who privately published his first book of poems in 1880 when he was a teenager. He attended Dartmouth College, graduated with honors in 1885, and was highly active in literary activities there, coming to write what remains the official school song. After college he seems to have considered various paths. He studied for a while in New York’s General Theological Seminary, taught briefly at Barnard College and Columbia University. In 1887 he met his Vagabondia co-author Bliss Carman, and true to their eventual series title, they spent some time tramping around New England. Hovey wrote that he decided to dedicate himself to writing on New Year’s Day of 1889 while viewing a solar eclipse, which seems somewhat magical for an epiphany, but yes, there was an eclipse on that date. In 1891 he began publishing a planned lengthy series of verse plays based on King Arthur’s court, and he seemed to have traveled to Europe around this time where he met writer Maurice Maeterlinck and took on the job of translating Maeterlinck’s work into English. Hovey was also enamored with the French Symbolist poets and did English translations of their work.

Let me set the literary stage for this young poet as he began his career: Verlaine, Rimbaud, and Mallarmé were still alive. So was Walt Whitman. So was Mark Twain. The first and just-posthumous volume of Emily Dickinson’s poetry was still in process. Ezra Pound was a toddler in Idaho. While Hovey was a college student, Oscar Wilde toured America giving lectures on Aestheticism.** Hovey and Carman, with their on-the-road poems of beauty and poetry, of wit over dour seriousness, seemed to have resonated.

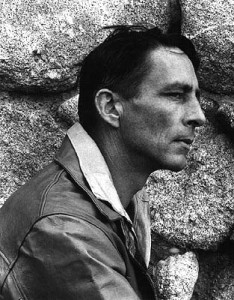

Richard Hovey around the time of the Vagabondia books. The woman here is his mother Harriet, not his “older-woman” wife Henrietta. A cousin who knew the young Hovey wrote that he “was so strikingly good-looking that I have seen people turn in the street to look after him.”

.

I learned one other possibly salient fact about the time Hovey and Carman were putting together the first Vagabondia book. In 1893 there was a sudden economic depression in the United States. Vagabonds were not always free-thinking college boys yet to establish their literary careers. Was there a sub-rosa political/economic point at the start of this series? There’s little I’ve found in the Vagabondia books that tip me to Hovey’s political stance, if he had formulated one.

I chose Hovey’s poem “Isabel” from Songs from Vagabondia partly because it was short and naturally suggested being set to music on first read. Given that I was also trying to get a grasp on Hovey’s life, I wondered who this Isabel might be. I didn’t find out. There’s no Arthurian Isabel, and I haven’t found any prominent Isabel characters in the works of Hovey’s literary heroes. I believe it was a somewhat common name in this era.***

Despite Vagabondia’s praise for male comradeship, I’m not (as yet) catching any homoerotic overtones there. Where eros does appear, it seems directed at women. The only romantic relationship I know for Hovey was a married woman who he had a child with and later married after her divorce. If you want to wonder at Hovey’s sexuality from afar, clouded in a sexually repressed time and with the small amount of information, I can only offer this tidbit: his lover and eventual wife was said to be “old enough to be his mother.”

Indeed, after all this search for biographic info, today’s poem might seem a tad insignificant. As a short love poem “Isabel” reminds me of Robert Herrick more than any of Hovey’s contemporaries, and she might be only a device to let Hovey write that sort of poem. In straightlaced society I suppose the poem’s breast-pillow line could have seemed 1894-era hot stuff, but I’m immune to that level of “I’m so naughty” eroticism — likely why Swinburne (also still alive in Hovey’s time) always seems laughable to me.

But Aestheticism holds that a poem doesn’t have to have great wisdom or weight as long as it’s beautiful, so I spent more than my usual amount of time with this 6-line poem’s music to justify asking for your attention to it. “Isabel” uses some of my favorite odd chords and flavors, and you can hear it with the audio player below. No player? This highlighted link will open a new tab with its own audio player.

.

*Father Charles Hovey was the President of what is now Illinois State University in its early days, and organized the 33rd Illinois Regiment (known as “the Teacher’s Regiment”) at the outbreak of the American Civil War, serving the Union as a Brigadier General.

**The fact of Oscar Wilde’s tour I first learned about from an episode of the TV Western Have Gun Will Travel. Those who knew him remember a young Hovey who seems to have taken Wilde for a model, dressing like him with colorful topcoats, long hair in a center-parted style, and dyed carnation corsages.

***I wondered about writers with that name Hovey could have read. The only hit in that search was the marvelous early 19th century folk poet, folk singer, and tavern keeper Isabel Pagan. Pagan’s poem “Ca’ the Ewes to the Knowes” was popularly set to music by Robert Burns, a poet who Bliss Carman extolled earlier in this series. I did read that Hovey either knew or took classes with Francis Child, of the famous Child Ballads collection. That the Vagabondia series calls itself “Songs” is evidence that folk song, at least of the literary variety, is one its elements.

The most famous poetic Isabel remains Ogdon Nash’s from 25 years later.