After my rewarding visit to the Carl Sandburg birthplace, our plan was to return to Iowa City and leave early the next morning to return home. I felt I knew more about the lesser-known early 20th century poet I’d come to find out about, Edwin Ford Piper, and I had had the experience of seeing something of Sandburg’s roots. My wife had gotten to explore several habitats. And I was pleased to find out my old body could still get around walking while carrying a 10 pound bag — even as a shade of the young student I once was.

Every trip is like this for me: enjoyment at the new place, appreciation of the new things experienced — but once the final day arrives, I’m ready and looking forward to returning home. But that evening as we were getting ready for bed, I was making a quick check of Internet things and saw that I’d received a response from S. L. Huang, a writer who had initiated my interest in the idea that Piper had been foundational in the University of Iowa Writer’s Workshop method of teaching creative writing students.

Why would I (and plausibly you) care about that? The Iowa Writers’ Workshop was the origin-point of some things that have become pervasive in creative writing: the MFA degree, the workshop method of developing writers and critiquing work in progress, and the practice of literary writers being brought in and paid to be instructors in such programs.

Little I’d read in the Edwin Ford Piper papers before the Sandburg finale had addressed that element of his life directly, but Huang’s reply said there was more info on this in his widow Janet Piper’s papers which the University special collections also had. I mentioned this to my wife — she was agreeable to leaving at noon instead of dawn for the long drive home, and she would find one more landscape to explore while I made the walk back to the library for a half-day looking at Piper’s wife’s papers.*

By now I already knew the routine in the special collections reading room. The tough part would be that Janet Piper’s collection was larger than her husband’s, and only generally cataloged. I had gone into the husband’s papers knowing at least a few things about him, but all I knew about Janet Piper were references that she thought “politics” had led to her husband’s early and sudden death in 1939 just as the Workshop was getting underway.

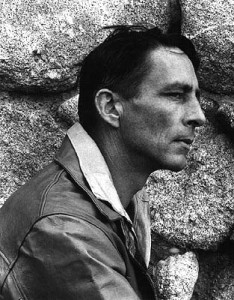

A small portion of Janet Piper’s papers in the University of Iowa collection, but my best guess at what might answer my questions about the beginnings of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

.

It’s taken me until the first day of July to read and comprehend what I captured for later perusal in those few last hours at the reading room. Later in June I also read Stephen Wilbers’ 1980 book The Iowa Writers’ Workshop which aimed to show how that noted program came to be. Wilbers corresponded with Janet Piper while researching his book, duplicating a slightly earlier attempt by Janet W. Wylder to get information from Edwin Ford Piper’s widow. Wylder was attempting a similar book on the Writers’ Workshop that was never completed.**

Janet Piper’s papers include correspondence from these two with her, and a more than 100-page, response that seems to have gone through several revisions and titles, eventually being called “Edwin Ford Piper and the Iowa Workshop: a prehistory.” It’s likely the best we have on the later adult life of Edwin Piper, who taught at Iowa for more than a generation and encouraged student creative writing throughout that time — right up until his sudden death just as the official Writers’ Workshop was launched. But spoiler alert: his wife’s account doesn’t live up to that promising title.

Since Janet Piper is even lesser-known than her husband, here’s a capsule bio extracted mostly from what I read in her papers and some web research:

Born (family last name: Pressley) in 1902 in Des Moines Iowa. May have moved to eastern Nebraska sometime in her childhood, and eventually attended college there and completed a Masters. She knew other young literary people in Nebraska and was already a poet who had won a couple of awards for her poetry while in that state. Began advanced degree work at the University of Iowa in Iowa City in the 1920s. Her academic work was interrupted by her 1927 marriage to Edwin Ford Piper, one of her professors, and by the following birth of their only child Edwin Ford Piper II in 1928.*** She writes little about the day to day of her marriage other than asides to the considerable duties of motherhood and being a faculty wife. She seems to admire and support her husband in his work and notes increasing change, stress, and conflict at the University then. She had resumed her academic work toward a PhD by the later 1930s — and then in 1939, her husband dies suddenly. She describes completing her final thesis defense in the midst of new widowhood in a disassociated state, flying on under auto-pilot. Various statements, some as corroboration, say this is likely the first PhD granted for a thesis consisting of creative writing.

She leaves Iowa in 1940 and within a couple of years takes up a teaching position at Sam Houston State in Texas, where she taught until retirement. In 1949 she made a suicide attempt by pills and was committed by her 21-year-old son to a facility in Texas, where she later writes she received the kind of coerced treatment, including electro-shock, that was common then. There’s some heartbreaking but formally-stated correspondence in her papers with her son from the early 1950s when they are estranged. She blames him for that mental facility commitment, and she says that he blames her for expecting too much of him as a child and not giving him appropriate attention.**** At her retirement in 1972 it’s written that she has continued to write poetry. She lives until 1997.

The Iowa Writers’ Workshop in their official histories started in 1936 — or it started in 1939 in other accountings. Edwin Piper had been encouraging students creative writing for decades, but the administration was now committed to allowing these efforts to be given academic credit and to become substantive toward degrees, a new concept for American academia. From Wilbers’ book and Janet Piper’s account, Edwin had some level of prominence in the mid-1930s in this now officially academic writers’ program — Wilbers writes it was more over the poetry sub-section while Janet Piper portrays her husband as being increasingly marginalized by the department’s administration, making the department head Norman Foerster a particular villain in the matter.

Yet, in a 1976 letter Wilbers includes in a footnote, a fascinating (but secondary to our story) figure Wilber Schramm recounts that he took over as director in 1939, being drafted into the job because of a pressing need occasioned by Piper’s death. In the Workshop’s official history, Schramm was the first director of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, but Schramm doesn’t tell it that way.

Alas, from what I’ve been able to find out so far, there’s no solid information about how central Edwin Ford Piper was to instigating those Iowa Writers’ Workshop changes to how literary writing and writers live and work in our century. His career shows he’d long favored working with young writers, but Janet Piper portrays that she and her husband didn’t like some of the leaders making Iowa a pioneer in granting degrees, or their matter of going about it. There’s a cryptic report from the 1930s that Edwin didn’t like how the Workshop was turning into a promotional effort which I cannot completely evaluate. I was at first skeptical at Janet Piper’s constant reference to the malign forces of something she calls “New Humanism” ruining her life, her husband’s life, and literature in general. I knew nothing of that term, but a little research confirms that that was overtly the flag that her chief villain Norman Foerster and some of his allies were flying.*****

For a person like me who likes to know how directional changes happened, to see what turned us from one path to another, it was engrossing to try to chase this down, even if the crossroads turned out to be shrouded in fog. I’ll close by saying I’d like to thank Edwin and Janet Piper. Though they are dead, and they likely never concerned themselves exactly with my questions being formed in the 21st century, their papers gave me a window into their times and challenges. I’d like to thank the folks at the University of Iowa Special Collection section who were always helpful to this old and informal scholar. And thanks to you, rare and curious readers, who granted attention to this 1930s couple caught up in the changes in American literature and this 2020s couple celebrating their anniversary with their particular interests.

Watching my time carefully, just a few minutes before noon I packed up in the library, went down to the street, and swung into the car as my wife pulled up at the entrance curb. We were leaving for home.

.

*Coincidence: as I went looking into the beginnings of the Iowa Workshop, she visited the Devonian Fossil Gorge which I later read famed Workshop Director Paul Engle also liked to examine while still a student.

**This double pump seemed to frustrate Janet Piper. She at first thanked Wylder for rekindling her memories of her dead husband and her time with young writers at Iowa. Piper’s response appears to be a version of the around 100-page memoir which includes a long side-discussion of New Humanism. In her following correspondence with Wilbers she’s upset that Wylder had in effect ghosted her, and she wonders why Wilbers doesn’t have the material she sent Wylder. Moderns, remember: this is the era when producing 100 pages meant typing that singular ms. entirely and inhaling correction fluid, not just cutting/pasting and pressing send, or dumping pictures off your phone’s camera roll.

***More notes for Moderns: I can hear the ick factor bursting in your minds. This sort of thing was quite common, even into the years of my youth. Their contemporaries wouldn’t necessarily think this scandalous — or even unusual — though the age difference (56 to 25) here is broader than many of these male prof/female student marriages. That said, everything you object to was still possible despite different mores. Janet Piper’s papers give no indication it wasn’t a happy marriage.

****Whatever led Janet Piper to her suicide attempt isn’t spelled out in what I’ve read. The number of stressors and level of endurance it would take to be a single mom, a widow, a rare woman/academic in an era when that was even tougher than today, and while society is in the transition from the Great Depression to a World War — all that might batter anyone’s defenses. Similarly, I can only imagine a 21-year-old son having their only parent, their mother, trying to kill herself and being put in a position to try to decide what to do about that. I don’t know the particulars of Texas law at that time, but authorities themselves might be pressing for civil commitment. I’m not suited to be a novelist, but reading in Janet Piper’s papers on this matter I thought “There’s a novel.”

*****Let me resist trying to give an outline of New Humanism. Like a number of Fugitives, New Criticism proponents, and neo-Thomists that followed this movement and somewhat evolved from it, they tended toward political conservatism, and in the 1930s many were, at the least, permissive of fascist authoritarians, which some (including JP) might lay to them being already authoritarian in aesthetics. Janet Piper speaks distressingly of fascist Iowa professors in that era, even names some. Janet Piper’s papers that I’ve read don’t tell me exactly what Edwin Piper thought of this. Though a Chaucer specialist carrying that interest into a project completed at the end of his life, Edwin’s papers don’t demonstrate a pervasive appeal to timeless classical truths, and his folksong fascination would likely oppose a tight highbrow/middlebrow/lowbrow outlook. I can’t say for sure what Edwin Piper’s politics were, but his widow seems left/liberal in the 1970s and makes no mention that they disagreed on politics back in the 30s. Janet Piper’s summary that “politics” led to her husband’s early death leads to the question: what level of politics? In her mind it appears university politics and civic politics were indivisible.

When asked about this era in the 1970s. Janet Piper continually wants to talk about what she views as more than a cultural tendency or scheme, and more at an active, effective, powerful conspiracy originated by New Humanism. At times she’s detailed and footnoted with her charges, at other times vague and implying great harms in a broader and fuzzier way. More than once in her papers she refers to Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and Conrad Aiken as the heads of a secret cabal advancing evil work — and I can’t quite “read” if I should take those expressions as satiric exaggerations. In a letter from Robert Hillyer, he agrees with her that she’s not a crank, using that word as if it had been applied to Janet. In what I read she spends less time than my curiosity would like expounding what she prefers in literary or cultural theory rather than what she damns.

It would take more study and knowledge to fully understand or evaluate that element in Janet Piper’s later writing. This element, often present in what I read, shows a life of great reading and learning exceeding my own, evidence of great energy for a person roughly my age — and likely at times I can’t quite measure, effective moments of literary criticism and insight.