I’ve mentioned this Fall that I’m on a project to clean out the accumulations of my long life. There are various battlefronts in this effort, but last month I worked on emptying my stuff from a small storeroom in my house, which was filled with boxes, some of which hadn’t been unpacked since I moved 40 years ago. One box was completely stuffed full of spiral bound notebooks.

I had once saved the notebooks I used in my high school years and then throughout my twenties. This meant a slowly growing cache of them had traveled from a tiny hometown in Iowa, to a dorm in a small college in that state, and then to the locations I lived at in New York for six years, and onward the four places I’ve lived in Minnesota.

I had a typewriter, which I used for some more formal things and finalized school assignments, and then in the ‘80s I got a personal computer,* but for 20 years or so, my creative work began and was recorded with handwriting in these college-ruled notebooks. Early, when there were only a handful of them, I mentally cataloged them by the color of their covers. Even after all these years I recall a couple of the earliest ones as “The Orange Book” and “The Green Book.” Like Emily Dickinson I didn’t always save working drafts, written on whatever was handy, but when I felt I had finished a poem I’d make a good copy in my most legible hand inside one of the notebooks to be saved.

I’ve written briefly at least once about starting to write poems as a teenager, and I won’t go on much more about that today, but I was surprised at the urge – it was not planned. I felt compelled to do this for reasons I couldn’t tell you then, or now. Living in my tiny town I had no idea how many people were writing poems, but I presumed it a small number, as the literature anthologies I had in school made me think the number at any one time was a select few. This misapprehension led to a grandiose feeling that I was writing poetry! – this grand art-form of literary geniuses.

Clearly there was a lot I didn’t know, but in my case this helped me, giving me a sense of accomplishment. Did writing poetry give me an unearned, unrealistic, sense of self-worth? Yes, I think it did – but we all need a minimum deposit in that bank, and that was the source I had. And after all I was a teenager, and few of that age have any substantial achievements.

In that process of pulling aside these old notebooks I came upon “The Green Book” that I recalled when there were only a couple of these, and I set it aside to look through first. In it I saw my good copy of a poem I remember quite well from my early work, one I had thought was one of my better ones then. Looking at it as an old man who’s read much more, written much more, lived much more, I think enough of it to present it here in performance today.

I didn’t have many poetic models to draw on, but this one certainly came from reading John Keats “Ode on a Grecian Urn” in my high-school literature class. I’ve performed Keats’ poem here, and I think I was already impressed at the ambiguity in the poem’s famous ending back then. My “Ode to a 1953 Automobile Ad” was on the surface a free-verse parody, burlesquing Keats classical art object – but I was at least partly conscious of wanting to make some solemn points too, though I don’t recall thinking out all the themes the poem includes, so my best recollection is composing the poem without knowing all I was including in the text under my pen.

I think there was a 1953 automobile ad in my memory, though I haven’t found the one described in the poem.** Sometime in my early teenage years, a man in my little town – no doubt doing the same “death cleaning” I am doing in 2025 – gave me several dozen 10-15-year-old Popular Mechanics/Popular Science/Mechanix Illustrated magazines. I devoured them, first because I adored the hyperbolic writing of the self-styled dean of journalistic automobile test drivers Tom MaCahill who wrote for Mechanix Illustrated – but this was a strange genre of magazine. Part reviews of new models of cars and novel ideas in consumer goods, part pre-Whole Earth Catalog handyman tips and project plans, and part more general writing about science and technology including predictions for the future.

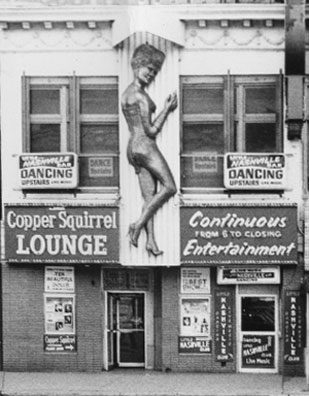

The soft golden car in front of a Greek colonnade, or a peaceful ride in a Paris that 8 years earlier would have been in the midst of a World War.

.

I enjoyed the time-travel aspect of reading these magazines, visiting as an abstract thinking teenager the world of early childhood. The too fantastic flying car future has since become a meme – but the junior historian in me would think: the Korean Conflict was being fought as some of these old pages went to press (little mentioned in these mags, little remembered now too), the new age of atomic war fear was beginning, and in the sixties as I wrote this poem, Vietnam was echoing the Korea situation. So, as the poem was being written, there was then too the feeling of a glorious and blest domestic United States – yet with a “conflict” acting as a far-off minotaur ready to take sacrificial children.

So, I wrote this in the 1960s linking those times in the 1950s, and sublimation of killing young men is the topic. Inexperienced as I was, I tip my hat to the images the young person that would become me put in there: the camera and/or coffin dark box capturing the bright sunlight of the ad, the rust-holes in the teenaged car as the wound in the son. The use of Whitmanesque (or Sandburg or Ginsberg in their Whitman mode) extra-long lines is not something I do much now, but as I performed them this week, they seemed to work well enough.

This old poem is now published with a musical performance in the lead up to the holiday that was once known as Armistice Day – the very day that World War I ended at a moment when it was just “The Great War” and didn’t need a number, and didn’t expect to gain one – but now our wars don’t get the roman numerals, though fantasy film franchises and Super Bowls do. We didn’t get flying cars. We got armed drones.

You can hear me performing my “Ode to a 1953 Automobile Ad” with the audio player gadget below. Has the audio player gone with Studebakers and saving old magazines? This highlighted link is supplied as an alternative which will open a new tab with its own audio player.

.

*My penmanship was erratic and not consistently easy to read, so a typewriter was essential for things of any length destined for others. But I didn’t do creative writing on a typewriter – something about the mechanical nature seemed an authorship firewall: the machine made the letters, keys and levers away from the writer, and one couldn’t easily cross-out and add little marginal changes as one wrote.

One of the things found in the storeroom with the notebooks was a postcard about requirements for receiving a rebate on what would be officially my first personal computer: A Timex-Sinclair bought in 1982 – but that tiny $85 plastic wedge wasn’t able to take over from a pen or typewriter since it had a small membrane keypad that was only useful to learn to write computer programs with. In 1984 I got a Commodore 64 which could do limited word-processing, but I couldn’t afford the software that did that. In 1987 I got an Amiga 500 which came with a copy of Word Perfect – the then leading word-processing software product – and I began a slow and inconstant transition to using computers to do initial drafts over a decade or so.

**The 1953 year of the car in the ad makes me sure it was a Studebaker ad, for a remarkably beautiful new 2-door coupe was introduced for that model year. When I look for examples of the ad campaign, I see many of the Studebakers are depicted in yellow, but never in a family tableau described in the poem in the ones I could find. And there’s the chrome bird hood ornament. Was I thinking of the Packard swan? Looking at pictures of the 1953 Studebaker I see there’s a 3-bladed chrome insignia on the peak of the hood – meant to be a propeller, or bird, or abstract shape? I appeal to Brancusi on the bird.