As I started doing some translations of Tristan Tzara, the man who was most famous for being one of the “Presidents of Dada,” I was surprised in more than one way.

Like some writers I’ve presented here, Tzara was known to me only by reputation, as a name, and that reputation was not only as a founder of Dada, but of being the theorist of its most nihilist and avant-garde wing. Dada as Tzara spoke of it seemed to say: let’s destroy everything, and see what remains. Sounds like a pretty fearsome guy, and from my generation’s punk rebellion in music, his reputation reminded me of the those just past the first wave of punk that bought into a first principle of denigrating everything that came before. That could be a useful corrective, a way to clear the creative mind from everything you feel has come to a dead end, whether it was “Tales of Topographic Oceans” or Tennyson; the horrors of WWI or the denigrations of Reagan and Thatcher. Such a stance, pure as it is, has dangers of discarding the baby with the bain-eau.

Tzara also provoked with ideas like his “How to Make a Dada Poem:”

Take a newspaper

Take some scissors.

Choose from this paper an article the length you want to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Next carefully cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them all in a bag.

Shake gently.

Next take out each cutting one after the other.

Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

The poem will resemble you.

And there you are–an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.

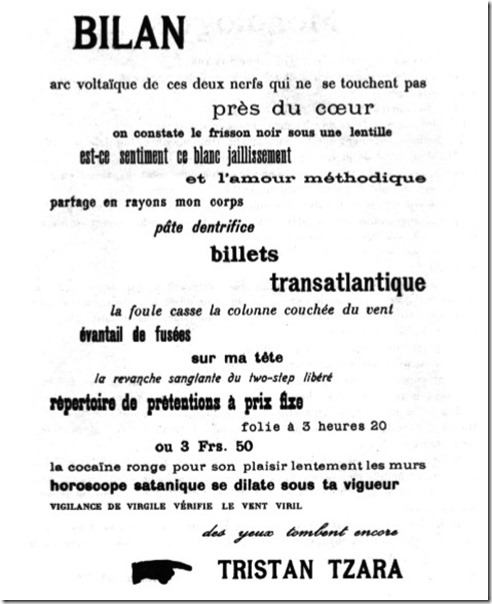

One can read this and miss the satire in it (particularly that last line); or one can read this laughing, and miss the value in this practice, variations of which were carried out throughout the rest of the 20th Century by Surrealists and Beats and unclassifiable modernists like John Cage. I, myself, independently discovered an analogous method as a teenager, and composing pieces by randomly opening a dictionary and blindly pointing with a finger at word after word. And Tzara did publish pieces that seemed to be just such an assemblage of words and phrases, for example “Bilan.”

Never Mind the Boustrophedon, Here’s a Tzara Poem as published in Dada magazine

Not only is “Bilan” typographically incoherent, the phrases are such things as “the bloody revenge of the liberated two-step” or “satanic horoscope dilates under your vigor.”

I believe this sort of thing can work: as a corrective, as a breaker of writer’s-block, as a reminder of the random and irrational component in creation, and as an insight into the dead and clichéd language which infests all societies. I think it works best in small doses when needed, and longer pieces based on it, or continued reliance on it, can be analogous to over-reliance on laxatives.

So that was the Tzara I assumed I would meet as looked for pieces to translate and use here with music: a man with little to say other than to point out with broken language that language is broken.

And to some degree that was reinforced as I looked at the few English translations available on the web of his work. Occasional beautiful lines, perhaps of accidental beauty, mixed with incoherent lines. Here is a link to an English translation of a Tzara poem “Vegetable Swallow,” though its translator is never credited on the several sites which have it with identical wording. This is the same poem which I use in today’s piece, but with my own translation from the original French.

I’ll talk more about what I found as I translated Tristan Tzara in my next post here, but I’ll summarize by saying that I found problems in the translation I linked to, surprising problems that sometimes feel to me a bit like reading the “bad quarto” of Shakespeare. I could be wrong in my interpretation of Tzara’s “Vegetable Swallow (Hirondelle Végétale)”— I am neither a scholar of Dada nor anything even close to a fluent French speaker—but I don’t even like the translation of the title, though I have kept it, because it may be what an English speaker is likely to know the poem as. “Hirondelle” is French for the species of bird, the swallow. I might have my own inevitable and anachronistic “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” connection with the swallow, but in the title’s context along with the English word “vegetable,” one thinks of that scary and prescriptive phrase from childhood: “Eat your vegetables”—not how it’d be understood in French.

Steve Jobs would have told the young Bill Gates (on the right) to try a black sweater

Tristan Tzara (on the left, photo by Man Ray) would have suggested a monocle.

In my translation, Tristan Tzara is providing something more like a Surrealist’s Lover’s Rock lyric—more Paul Éluard than Dan Bern hilariously parodying Bob Dylan. Musically, I’m not attempting reggae though. I’m not even sure what genre to call my composition on this one, but it is, like Tzara proclaims, “Swimming in disparate arpeggios.”

To hear it, use the player below.