A break in the influences as memoir series here, that theme that I’ve fallen into doing for National Poetry Month? Maybe. I’m going to present a new performance of a Carl Sandburg poem — but before that I’m going to talk about another writer, Rod Serling. Serling wrote a variety of things, but he’s best known for creating and hosting, often presenting his own scripts, the mid-century TV show The Twilight Zone.

I’m doubtful young people watch the old gray half-hour Twilight Zone episodes anymore, though they are still available in various ways — but people younger than me certainly did, and to some degree still do. That generation between today’s youth and my old age has sought to revive it under its original title or in spirit, and they still talk between themselves about the original episodes and their hard to reproduce sensibility. I remember being in a creative writing class back in The Seventies, with folks maybe five years younger than me, and I was surprised at how often they might refer to some TZ episode instead of a Greek myth or some piece of literary poetry. SF/Fantasy fandom has grown a hundredfold since, it’s the backbone of popular narrative culture now. The SF/Fantasy memory-hole village that was Twilight Zone’s once, has become a crowded inner-ring suburb, neither new-hot nor charmingly old-fashioned.

One episode of that series, one that came early in the show’s 156 episode run from 1959 to 1964, appears on some of the middle-generation’s “best of” lists, though I think there’s a strangeness that it does. Titled “Walking Distance” it’s tied very clearly to Serling’s own Greatest Generation memories, not as much to my generation who might have watched it on its first run, and I’d expect not-at-all to those younger than me. To summarize the plot without spoilers I’ll say the story is that an overworked and worried 1960 advertising man ends up walking in the countryside and enters his old hometown, the allegorically named “Homewood,” where he grew up before he left for New York City. He finds it not the present town in 1960, but the town of the 1920s.Given the number of time-fantasy stories written since then, not that unique a setup.*

Well, is a poem about a poet hearing a bird sing, or mourning a dead intimate, or finding themselves awash in desire all that unique? “Walking Distance” works, if it works, on performance and from the strength of the slightly wordy** but emotionally resonant script. A feeling of nostalgia — more than that, the feeling of wanting to be able to walk one’s childhood places in dimensions more palpable than memory is something easy to evoke in us. Serling’s script wants to draw a bit more than just all the feels in this situation — but let’s face it, all the feels, the range of edges soft and sharp of them, is the powerful engine here. That engine is strong and universal enough that I can feel the lost 1920s that Serling evokes, even if I never lived them.

Which brings me to Carl Sandburg and today’s poem for performance, “Band Concert.” Published in 1918, it presents itself in a poetic collection of contemporary portraits of American places and people that Sandburg has observed in his travels. The night of the band concert in this poem — while in Nebraska instead of upstate New York — is closely contemporary to Serling’s Homewood. Poet Sandburg is roughly 40, so while the scene in his poem is set in the now, the poem views the kids half his age re-enacting things that are already past for our storyteller.

If one knows the history of American music, Sandburg can be decoded as knowing that the Nebraska city is a few decades behind Chicago or New York. The band seems to be playing rags, the craze of the turn of the century, not of 1918. A small-town kid who had long left for the biggest cities in America, Sandburg can compare the giggles of the kids to the “Livery Stable Blues,” a landmark early Jazz recording where white musicians produced outrageous instrumental sounds imitating farm animals. “Livery Stable Blues” was released in 1917, and Sandburg was an early Jazz-bug — but he’s not knocking the Nebraskans for their music. He’s celebrating it, and them. And after all, cowboy rags and Negro*** rags, would be in the repertoire of Carl Sandburg the folk musician who would be including a set of guitar-accompanied songs in his poetry readings.

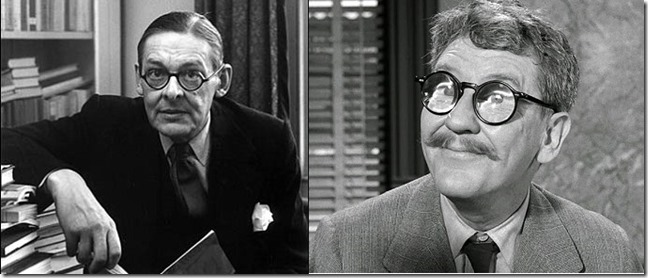

Homewood’s park and our 1960 visitor, dressed much as script writer & host Serling would be. Town square park and bandstand from my grandmother’s town. Bandstands in towns were common enough in my Midwest, so I forgot this elegant one, but I did remember the alligator.

.

In time-space, I’ve never visited Serling’s Homewood, nor the Nebraska place Sandburg is reporting from. Those are my grandparents’ times. In my own midcentury I’ve been to their outskirts close enough to see the band pavilion in the park or square, the full summer dresses, farm boys when that was a common occupation rather than employees of feed lots, and I’ve walked the sidewalks past the lattice shadows decorating porches. I can translate some from their writing. Serling, Sandburg, my grandparents, they know “more of the story.” Which is us — time, space, placental barriers away.

You can hear me perform Carl Sandburg’s “Band Concert” with a rock quintet which has no tubas nor cornets in this concert. Audio player gadget below, alternative link here for those who don’t see a graphical gadget.

.

*Twilight Zone itself did another well-loved episode later with a very similar setup: “Next Stop Willoughby.”

**As if poets have standing to complain about the use of words to portray things, rather than filming a chase, fight scenes, or calling in a CGI render farm.

***Those who go to the original text linked here will note that Sandburg uses the n-word in this poem as he does elsewhere in his early poetry. I’ve “translated” it. Sandburg also uses the general range of derogatory ethnic names of an era where “white” by the conventions of today wasn’t then a monolithic block, but instead was segmented into many othered creatures to be devalued with rude names and determinatory stereotypes. I’m not a Sandburg expert, nor am I the one to rule on what’s racist and what’s documentary, but what I’ve read of Sandburg says to me that he was intentionally anti-racist.