Last time an Afro-American 35-year-old singer and skilled guitarist named Hank Hazlett had left The Cats and the Fiddle, a swing Jazz quartet made up of Chicagoans, when that group’s founding and featured singer returned after serving in the armed forces during WWII. Hazlett had been standing in for that man, and though he never recorded with the Cats* he got experience touring the best Black-oriented entertainment venues of the 1940s and interacting with other acts that the Cats shared bills with.

Hazlett must have decided he was comfortable fronting a band. In the scrapbook that is the centerpiece of this series, we can find two posed large-format glossy promo photos taken at a professional studio in Chicago of his next act: The Hank Hazlett Trio.

Interesting pairing visually. One with all black suits against a white background, the other all white against a black background. Could be simple use of contrast, but the poet in me sees metaphor.

.

That photo studio location indicates they were formed in Chicago. The trio was touring in 1947, as the scrapbook contains a letter from a San Antonio radio station thanking the group for an appearance there. I’ve also found this ad for a 1949 Trio appearance in Denver.

The Cats and the Fiddle had played Denver more than 10 years earlier in an early gig before Hazlett joined up. By now this venue says it’s in “The Heart of Denver’s Harlem.”

.

Unlike the scrapbook material from Hazlett’s Cats in the Fiddle stint, there are no clipped-out ads for appearances by the Hank Hazlett Trio pasted into the scrapbook. We don’t know who sang in the Trio, and I can’t be certain what kind of music they played either. The rapid, chopped chord-change swing Jazz of the Cats was morphing into what was renamed as Rhythm and Blues, a term invented by music journalist soon to be Atlantic records principal Jerry Wexler to replace the previous music business term “race records.” R&B could include former Jazz band vocalists who now fronted small combos, vocal harmony groups like the Cats or their more successful and smoother contemporaries the Mills Brothers and the Ink Spots, and the newly plugged-in Black rural and southern singers who had moved north to play a gruffer, harder-edged electric Blues. Basically R&B was rock’n’roll, just not named that yet, and with a much smaller white musician contribution when the term was coined.

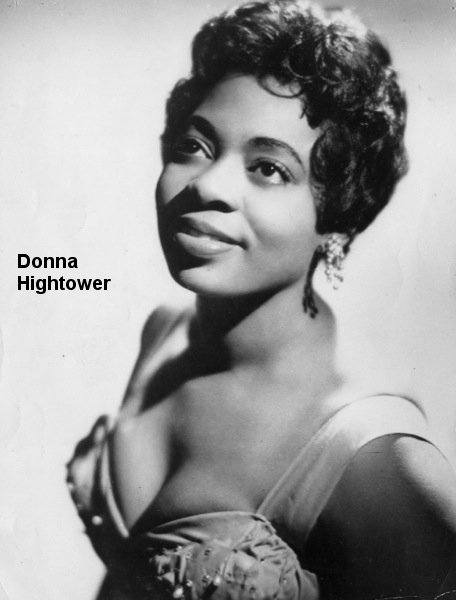

The first reports I can find of the Trio performing has them backing a Missouri-born by way of Chicago female R&B singer Donna Hightower which are collected on Marv Goldberg’s website.**

The Cats had played as a band for female singers, including backing Lena Horne with Hazlett on guitar.

August 1952 Minneapolis Spokesman (another Black newspaper) wrote this:

The musicians who are playing at the Key Club are Hank Hazlett, leader and Spanish guitar; Maurice Turner, bass fiddle; Buddy Davis, piano and vibraphone; Donna Hightower, Decca recording artist and vocalist. The musicians are all from Chicago and staying at the home of Mr. and Mrs. William E. Gray, 420 E. 37th St.”

That “staying-with” address is in the heart of Black South Minneapolis and would be two short blocks from a Portland Ave address we’ll meet just down the page. Goldberg has them playing at the Key Club in a long-term engagement until New Years Eve. Here’s what the St. Paul Recorder (the other Twin Cities Black newspaper) has to say (with Goldberg’s interjected corrections):

The Hank Hazlett Trio, composed of Buddy Davis, pianist and Maurice Turner, base [sic] drummer, along with the capable leader of the combo Hank Hazlett is now playing at the Key Club, 1229 Washington Ave So., every night and Sunday afternoon matinees.

The popular trio featuring Dinah [sorry Donna] Hightower, vocalist, got its start in Chicago in 1947 and has played successful engagements in many outstanding nightclubs.

Miss Hightower with her ultra modern version of popular music, seems to have a way with the patrons. The entertainers will be here through the holiday season.”

Don’t look for it now, this location was demolished for the I35 freeway.

.

If you want more details about The Key Club aka South of the Border, the Twin Cities Music Highlights website has much to read. Many national Jazz and R&B luminaries played at this establishment in the Seven Corners portion of Minneapolis’ West Bank neighborhood. Lots of seedy goings-on too, as this era of the Minneapolis Jazz and music scene often finds stripper acts, guns, and likely mob connections intermingling with the musicians.

This YouTube video dub of an acetate (demo or proof record) is the only audio artifact of the Hank Hazlett Trio I’ve found. Donna Hightower sings backing vocals. The guitar and likely the lead vocal is Hank.

.

Around the time of this extended engagement, it seems that Hazlett moved to the Twin Cities, setting up residency at 3648 Portland Ave in South Minneapolis, six blocks from where the scrapbook was found. Why there?

From what I can gather, Minneapolis has a strange and complex racial history, so please excuse these meager paragraphs that try to summarize the highlights of my incomplete understanding that follows. Minneapolis has long had some Black residents, and when it gathered more in the first waves of the Great Migration after WWI, there was white backlash. One instrument of that backlash were special clauses put into property deeds excluding transfer of those deeds to non-white or Jewish buyers. In theory government courts would need to be called in to enforce these racial covenants, but in practice these were often a silent exclusionary agreements, though they were sometimes enforced in breach by mobs of sullen whites who would surround an incursive Black occupied home with threats and vandalism against this blatant integration. This private customary segregation was later reinforced around mid-century by “red-lining,” a practice by home-loan issuers (including federal government loans) to exclude writing mortgages in Black areas. All of this, pretty rotten stuff — but perfectly “normal” and widespread in the United States, not just Minneapolis.***

In Minneapolis there were two sections of the city that became “Black:” one, on the north side of town (shared with a Jewish population that were often excluded by the same covenants and a higher than usual American level of local antisemitism), and the other, a vertical north-south strip in South Minneapolis. 3132 Park Ave was just on the borderline of these redline established sections. Even when I came to South Minneapolis in the ‘70s, you could see by the skin tones of the residents where those invisible lines sort of remained, to a fine resolution that could be almost block by block.****

Our 1953 musician Hank Hazlett lived in a house in the Black South Minneapolis area for several years, his only Minneapolis residence I can establish. I don’t know if he owned it, but the scrapbook maker was proud of it. There are a couple of photos clearly identifiable as his house, one with a new-looking or late-model 1953 Cadillac parked in front. I don’t know what his income was. The city directories continue to list him as musician, and at least in the mid-50s his local gigs were common. Even this late in the 20th century, when radio, television and recordings allowed music to be captured and transmitted on devices, live music was still a vital part of the experience of music. Perhaps for Hank the choice of Minneapolis went like this: I could tour from any city as my home base. The music scene in Minneapolis may be smaller than Chicago or LA, but on the other hand there are fewer Black bands competing for the club slots — and since it’s not a town to launch one’s new act to musical stardom, my middle-aged self may be able to settle down without having to directly compete with the most ambitious young acts.

One of the pictures of 3648 Portland Ave in the scrapbook. I’m assuming the car is Hazlett’s. The scrapbook has 1955 telegrams directing Hazlett and his trio to go from a gig at Williston ND to Sheboygan WI and that Scotts Bluff in Nebraska is cancelled. If they drove, that’d be a good car for this.

.

The city directory records tell us that he had a wife, Edith. It could be that the marriage predates 1953, and there’s certainly lots of 1940s material in the scrapbook if she collected any of it then. There’s a possibility they have a child. The scrapbook is oh so scant on this. There are three photos of young children on its pages. The oldest by background clues may be as early as the 1940s, and it shows a young toddler standing in a quiet road that is not Portland Ave, and in pen on the bottom it says “Earl P. Jr. 2 years old.” Lawrence/Hank Hazlett isn’t Earl, and “Jr.” traditionally means a father’s name given to an offspring. And then there’s a pair of what looks to me like two snapshots of one child. One shot of this kid shows a smiling sub-1-year-old in their onesie. To the right of that photo is pasted another one of a young Black couple sitting in front of moon and stars backdrop. That man doesn’t look like Hank Hazlett to me, but not only are the two photos near each other, I can sort of see the baby looking like the child of that couple. It’s possible that the man in the moon and stars photo is a much younger version of the performer Hazzlett, who I have only older-age pictures of. And finally there’s a somewhat serious looking, slightly older child in a push stroller-scooter. The back of that last photo has a date: 1952.

This is the second set of baby pictures that I think may be the same child. The one in the middle is dated 1952. Do you think the moon & stars picture that’s pasted on the same page as the left-hand baby is a younger Hank? There’s another picture below of a woman that may be an older Edith Hazlett.

.

There’s also a handwritten, child-like letter which I transcribe as:

Dear Daddy,

How are you? Fine I hope.

And all the others. We had a vary nice Christmas. Well today is the last day in the year and a new year is coming. Yvonne Dickie Gwen and myself are getting along fine in music. I love my fountain pen. We all like our fountains very much, our pens write fine.

Thanks for the money, Daddy. We were very glad to hear your voice. I have been over to whites ever since last Friday. White has a lot of Christmas cards. They are very pretty. Yvonne and Dickie White has a beautiful Christmas tree. I am glad you liked my present, and I know that picture is a good picture. White Chick and Marshall like there souvenirs very much. Well goodbye and good luck. With a lot of love

Felicia”

This could be an “on tour” letter to a traveling father from home — New Year’s Eve is always a prime gig opportunity. Or it could mean that the child doesn’t live with her father. Someone chose to put this letter in the scrapbook, and I believe the scrapbook was made by Hank, his wife Edith, or the two of them in collaboration. Knowing more would change the meaning of the letter.

Let me be clear: a musician’s life, particularly a touring musician, detracts from marital stability. Incomes change rapidly. Travel and late-night hours bring separation. Alcoholism and drug problems are endemic. Egos swell and are crushed and those changes can abrade a relationship.

The Minneapolis city directory tells us one more thing about Hank Hazlett’s home life. In 1958 the city directory records that Marian M. is now the wife at 3648 Portland. Marian is also listed as working for the Minneapolis Public Library. Hank is now 47, and the city directory doesn’t say “musician” next to his name — instead it says “banquet formn Dyckmann Hotel.” Same in ’59. In 1960 and ’61 Hank is shown at the 3648 Portland address, but he’s a musician and working at the Flame in Duluth, 150 miles north. In 1962 and ‘63 the musicians place of work is listed as the Manor House in St. Paul and the Downtowner Motel in ’63. Marian remains until the most recent city directory available listed as his wife.

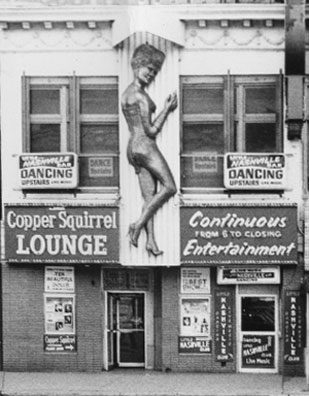

The last Hank Hazlett Trio gig I have found a record of was at a strip club/lounge on Hennepin Ave called “The Copper Squirrel” in September of 1963.

Site of the last known Hank Hazlett Trio gig.

.

I’ll admit, like someone looking at amorphous clouds in the sky I can picture these scenes: Marian isn’t necessarily up with the musician’s lifestyle. If Edith is the maker of the scrapbook or a collaborator in making of this document largely about her ex-husband’s life and music career she may have taken it with her. Out of spite or from fond memories of their days together? Maybe Marian didn’t want that scrapbook mostly about Hank’s earlier life around anyway? Who can say? Maybe it’s something else. There are no pictures in the scrapbook I can say for sure are post-1958. If Hank was the one making the scrapbook, maybe he had tired of documenting things.

Here are two picture which look like they could be the same woman found in different parts of the scrapbook. The man is Hank Hazlett, and I suspect that the woman would be Edith Hazlett prior to 1958. Edith may have been the person who made the scrapbook of her husband’s career, and may have been the one who put it in a crawlspace to be found in the mid-1970s.

Here’s a quartet of scrapbook photos of the Hank Hazlett Trio performing.

Hank with an Epiphone archtop in most of these photos, but a “blackguard” early ‘50s Telecaster in one. In the upper right there’s a woman holding down the pianist’s spot in the trio, and the white bass player there is crossing time and space with that tie he’s wearing to protest Donald Trump’s haberdashery sense and opinions about Black History Month.

In our next post we’ll track back a bit and talk about how the scrapbook includes the home-front World War II experience and what else it shows about American mid-century race relations and Afro-American cultural pride.

.

*The WWII years caused considerable interruption in recording activity. Shellac, the hardened resin that 78 RPM records were made from came from a residue produced by overseas insects located across a warfront Pacific Ocean, and there were strikes by musicians labor organizations as they tried to extract concessions from entertainment companies during this time too.

**I’ve mentioned Marv Golberg’s site multiple times in this series. It’s full of marvelous details about Jazz and R&B artists of this era. Thanks, thanks, thanks, Marv.

***Just after the end of WWII the practice of racial covenants was taken to court, and in an early post-war civil rights victory, they were struck down nationally, but redlining was not addressed, and “it goes without saying” agreements to hew to segregation continued. Yet at the same time in the late 1940s, a young Minneapolis mayor Hubert Humphrey saw to enactment of an early law against racial discrimination in hiring, giving promise that more job opportunities would open up for Black residents.

****By these 1970s properties in these parts of South Minneapolis were affordable, assuming you could swing the finances, because it was still considered a “bad part of town.” This led to some kinds of mostly young white people to move in: gay folks, and Boomer “hippies” and political radicals. Some of that generation are still alive, and still live there, and there’s a new influx: immigrants from Africa and Latin America.