I left a comment on the Fourteen Lines blog last month when I saw he’d posted this Kenneth Slessor poem. I didn’t know the poem, but I wrote that blog’s host that he and I may be the only Americans who appreciate Kenneth Slessor.

Slessor is an Australian poet, and Australia is a long way off, but then over in our hemisphere we’re not obligated to keep all the poets of the first half of the 20th century in mind either. I know little about his life other than the short-ish Wikipedia article. I did a more elaborate search a few years back, and I recall he was considered by some as a pioneering Modernist in his country.*

Some of his poems I’ve read don’t move me on encounter. There are elements in his verse at times that vaguely remind me of a troop of other British poets contemporary to Slessor in the U. K. What is that that leaves me cold in that field of first half-century British poets? Stilted, too formal language, non-vital metaphors, musicality that can only barely contest those first two failures. This could be my failing, my taste may not be yours, and another apprehension (mis or otherwise) of mine is that there’s a whiff of posh-boy entitlement and clubishness in too many. I’m a Midwestern American, I could be wildly misjudging this. I make no claim of authority.

But no matter that, because his best poems move me like few other pieces of verse can. They have Modernism’s Classicism streak, that idea that the poet doesn’t always presume to tell you what the characters in the poem think, nor does he directly tell you what to think about what goes on, even though the selection of what he portrays intends an effect.

I know nothing of Slessor’s poetic influences.** In the Wikipedia article someone says he was compared by someone favorably to Yeats. I’d have to squint to see that one. Someone else said Baudelaire, and I can see that somewhat, though Slessor avoids the bad-boy-boast persona. Indeed, in my favorite Slessor poems, he’s not in them at all, he’s just the observer, and we only know him by his senses — which as we read those poems, become our senses.

Such a poem is “Wild Grapes.” I can see and smell the marshy landscape, the broken orchard, and the sight, the shape, the texture, the musky taste of a wild black grape.

Isabella grapes, not a greatly loved variety by connoisseurs.

.

Then as the poem reaches its penultimate stanza, a bit of mystery arrives. There is a sense there of a ghost, a “dead girl” named the same as the grape variety — and as the poem moves to its conclusion, seen as a union of the two, before we move to a final disturbing line.

Ending poems is hard — at least I find it so. I could generate a hundred good starting lines, and yet with the same effort still not come up with a single good last one. Slessor’s last line grabs me. There’s a reason the ghost’s spirit stays in the deserted place. Maybe it’s her similarity to that wild black grape. Or maybe it’s some emblazoned event, before the orchard was abandoned, its sweet fruits of apple and cherry still tastable and ripe. The poem’s voice only suggests: kissed or killed there. Is there a dichotomy, a distance between those two suggestions? Perhaps Slessor intended that — but here’s what I think: I read that line, implying an “and” not the written “or,” as a vivid allusion of sexual violence.***

You can hear my performance of Kenneth Slessor’s “Wild Grapes” with an audio player many will see below. No player? This highlighted link will open a new tab with it’s own audio player.

.

*He wrote poetry between the end of WWI and the end of WWII, so not in the very first wave of Modernism elsewhere, but Australian culture might have lagged a bit from Britain, France, and the U. S.

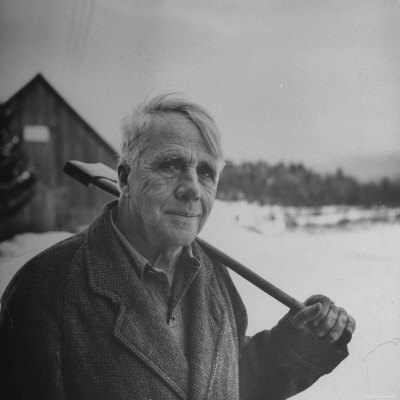

**I can see Rilke and Robert Frost in his poetry, and there’s nothing outlandish to think he might be familiar with their work. A prominent object in this poem are grapes, and I thought of this poem by Rilke, and this one by Frost, which also feature that fruit — but I don’t know. Though my favorite Slessor poems are more sensuous, there’s an epitaph character sometimes that reminds me of a somewhat forgotten early American Modernist, Edgar Lee Masters.

***I suspect more women, from more experience of violence chained with sexuality, would see that reading. Slessor wrote “or,” and his typewriter had other keys if he wanted to use them. He could just be musing on a range of things and the unknowability of the lives on what sounds like a plot once occupied by lower-class settlers or convict exiles from Ireland.