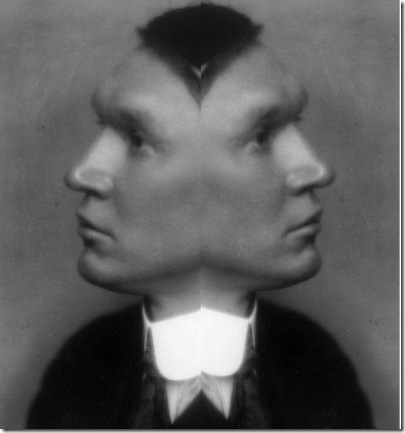

The month’s name January is derived from Janus, the Roman god of gateways and change, conventionally portrayed as a being with two faces: one looking forward, one backwards. And we have a new year, a place to do that – although this New Year’s Eve, someone revived a quote ascribed to a telegram sent by Dorothy Parker to Robert Benchley on New Year’s Eve 1929: “You come right over here and explain why they are having another year.”

A Roman bust of Janus. You know one of the tough things about having a beard? Trying to trim it symmetrically in a mirror. Now imagine Janus trying to do this.

.

I have a musical piece today, one using words by an unusual Modernist, Vachel Lindsay who published this poem in 1929. Though the poem mentions footprints in the rain, when I read it, I immediately thought of walking or riding my bike in the snows of Minnesota. In the up and back of those trips, often taken in the early morning, I’m conscious of the fresh tracks I’m putting down in the snow – that they are marks of me being there, moving, while I think of this act. On the return leg, I sometimes get the notion to look for my tracks from earlier in the morning. Looking down, I can never find the exact pattern of my treads – more falling snow, or wind, or others tires and feet have obscured them.

“We met ourselves as we came back.” Vachel Lindsay for January

.

What was unusual about Lindsay? This later poem of his wouldn’t look so out-of-place on the page with his contemporaries, but he came to poetry through a long tramp, and several times before WWI he took off as an itinerant on long walking journeys through parts of the United States carrying a sheaf of poems he called “Rhymes To Be Traded For Bread.” To some degree this romantic notion worked, but his breakthrough occurred when he was noted by Poetry, the Chicago-based magazine of the new literary poets. After that, Lindsay became known for public performances of his poems in a boisterous reading style with the energy of waving arms and a booming sing-song vocal cadence that he unapologetically called “Higher Vaudeville.”* Some likened his performances to Jazz, but as I’m made a point of noting in other posts here: in the 1920s that didn’t mean “an art music consumed mostly by connoisseurs,” but a raucous and uninhibited sacrilege. Some recordings of Lindsay exist, but I don’t know how he would have read this particular poem. I decided to do a full Rock quartet setting, and I’m banging a tambourine as I performed his words. You can hear that performance of Lindsay’s “Meeting Ourselves” with the audio player below. No audio player? You don’t need to retrace your tracks, some ways of reading this blog suppress showing the player – but you do want poetry with electric guitar and a guy slapping a tambourine, don’t you? I don’t ask for bread, but you can use this highlighted link which will open a new tab with its own audio player. Want to see the poem on the page or read along? Here’s the link to that.

.

*Lindsay has largely fallen off the literary canon podium, but his hyper-expressive reading style might have traveled via incorporeal and non-literary spirit mode to the more outlandish Slam poets of my lifetime. I’m unaware of any other poets back in the last decade called The Twenties who sought to emulate Lindsay’s controversial style exactly, but live performances of literary poetry, even with music, were not unheard of. Carl Sandburg before he became a published poet, tried to make his living giving lively Chautauqua lectures on the topics of the day, and after his Pulitzer Prize for Chicago Poems, he took to performing folk songs along with his poems at readings. William Butler Yeats, whose poems so sing on the printed page, floated a serious effort to have his poems performed with music, only to receive decidedly mixed reviews for the results. Both of these poets knew Lindsay and had some appreciation for his verse. It might be supposed that by being so outlandish in public, Lindsay allowed them cover for a quieter, but still expressive, poetry performance style.

How about Afro-American poetry performance? In the reverse of his “poems for bread” trade, Lindsay recommended Langston Hughes poetry to others after Hughes, while working as restaurant staff, handed diner Lindsay some of his unpublished verse. Hughes recognized the wider modes of Jazz and Blues ahead of many, and melded it into his poetry. Lindsay’s poetry reading style also referenced extravagant preaching styles, and early Chicago Black Modernist poet Fenton Johnson, a contemporary of Lindsay, put that rhetorical expression into his poetry.