We left off last time in my Black History Month series this year, with a crumbling scrapbook filled with mid-20th century things someone had gathered. The scrapbook compiler was concerned with entertainment, particularly Afro-American’s in that role, and the largest number of items they’d pasted in focused on a somewhat obscure musical act: The Cats and the Fiddle. Was the compiler a fan or a musician themselves? Woah, we get ahead of ourselves. Let’s stay with the musical evidence we have for a little while longer.

Once I get out of bed in the morning, I grab a newspaper from somewhere in the vicinity of my front door and read it. This is antiquated behavior. I often linger in bed before or after sleeping reading near-instant news on a large tablet connected to the Internet before I later get to the morning paper’s headlines that were written yesterday, yet still I take comfort or distress from reading them printed on paper. This is memory/habit working. I’ve read a newspaper in the morning since shortly after I learned to read. I even delivered them door to door as a youth in my little Iowa town, a place where and when the newspaper might be the only way you’d find out about some things in any detail.

Though I compose music and operate various musical instruments constantly as part of this Project, I’m somewhat removed from the general life of a musician today though I read accounts, I observe. But all of us listen to music, experience it some way. I know of no culture anywhere that for any appreciable span of time has been without music.

In the 1940s and ‘50s world the scrapbook photos, magazine clippings, and ephemera collected would have overlapped my childhood, would have been my parent’s adulthood. I experienced music some from records, some from television or movies, and largely from radio.* Music face to face? Church music once a week, and the school’s student marching brass band a few times a year. I enjoyed rock’n’roll cover bands just twice, at the Junior and Senior proms in my high school. Concerts? I once got to travel to the large auditorium at the state capitol to hear Handel’s Messiah oratorio. But that’s a rural, small-town story within a family that had no special connection to music, played no instruments.

For other white folks in cities, and in other areas, music could have been more central, more direct. Step back a generation to my grandparents’ youth? Recordings, perhaps some, radio not yet broadcasting, movies silent. Non-commercially, there was the parlor and folk music of those whose neighbors or families played. Music at events meant musicians playing, making the entirety of the noise right there and then. Let me repeat: that era’s connection to music was almost entirely performer in the room or performance space — and so where you lived or traveled to impacted your music heavily, and overwhelmingly your connection to your music was as fully dimensional, occupying the same space at the same time with you.

Some who read this may be two full generations younger than me. Your connection to music will likely be more removed: streaming playlists, the soundtrack to video games, concerts that could be large TV screens over a distant stage of dancers and miming singers with microphones in their hands. Or it could be a sweaty basement or a club with a small stage at one side, or something you try to record on the ubiquitous computers surrounding us, to hopefully exist elsewhere momentarily on phones, like a brief, wrong-number phone call that each connected party, embarrassed, occupies briefly, and leaves. You may think: I decide how I experience music, or how I make music! Yes, you do have choice, even if you may, out the other side of your mouth, decry that most all others are dictated by culture and capital. The in-between truth is that you, musician or listener, and the musical audience and musicians in general, are still living inside a present culture that changes things. The older ones living now still remember past cultural contexts, a diversity of time.

Because Afro-American representation lagged in mainstream American culture, representation of their music in mass media was filtered out, shown behind a screen for much of America. A Black American circa 1930-1960 is going to make and experience music because of their contemporary cultural particulars, their landscape in time. How long this post would be for me to try to even outline or list those things I think I have a smidgen of understanding of: the divide of parochial cultural ignorance from non-Black folks can fill volumes, Black History Month a pitcher of a lakeful. Demeaning white superiority, colonial European cultural hierarchies, and minstrel show comic-fool stereotypes are the proscenium for Afro-American performers. Sometimes violence lurks at the meeting edges. A well-meaning paragraph in a blog post staggers to carry that weight.

So then, if a Black American was going to use music to relax, or as a balm against the absurdities of your life and times, how much easier is it going to be to find that in Black entertainers, in Black saturated places among fellow Black audience members. But also consider: your experience of music is going to be that fully-dimensional one most often. In the room. In the same time. You can smell the music, which you can’t on Spotify.

Think back to that short movie clip from the previous post in this series,“The Harlem Yodel.” The Cats and the Fiddle and the Dandridge Sisters are dressed up for the Alps in the roomful of mirrors that we’re to know to be an indoor ski meet. It’s 1938. I notice as the Cats enter our frame at one minute into the video clip, they drop a short series of sour, single string plucks. Is that a musical Dada expression saying: we know this is ridiculous, but we’re getting to be in the MGM movies, even if it’s a B minus, undercard short-subject? One of the producers of the short, Jack Chertok, would work on more than 30 shorts in 1938. By the early 60s he’d be the producer of My Favorite Martian, a half-hour TV sitcom about an undocumented extraterrestrial alien living incognito on a grey-scale Earth — not exactly Ralph Ellison, but some of the strangeness is intentional. In the movie, the audience is white.

White folks on the right: “What, we can’t even have segregation at an indoor ski jump competition?”

.

In the second music clip, “Killin’ Jive,” the audience is black in the film and in the producer’s movie-house intent. It’s from one of a series of Westerns made for Black audiences, and the picture’s star (unseen in the clip) is the “Sensational Singing Cowboy” who was variously billed as Herb or Herbert Jeffries or Jeffrey. Wikipedia decided on Herb Jeffries, but I don’t know if the last name varied for carelessness or branding tweaks. His Wikipedia article goes on to write about the unsettled ethnic background of the man born Umberto Valentino, but he was clearly marketed at the time as an Afro-American. The band’s performance there is intense and uninhibited — can’t-top-this showmanship. This clip, and publicity photos, would mean that the Cats would need to do this live on club stages at some point in their sets. This song (like many in the Cat’s recorded repertoire) is by a member of the band, and “Killin’ Jive” is, full of insider Jazz/Black slang. Here’s a link to the lyrics.

Clearly, it’s a song about marijuana intoxication, and it’s performed in a let’s-get-high-and-party manner. The lyrics, which as I said are written by one of the group’s founders, Austin Powell, can be read as adding an undercurrent to that performance. A line is refrained in the song “He’s a sad man, not a bad man,” and I expect “bad man” in Thirties Jazz argot could carry the same “formidable and unrestrained” (in this case, when high) Afro-American slang meaning as well as the mainstream cultural meaning of he’s not evil, he’s just depressed. There are lines too about “darkest days” and “got no rent” (not transcribed correctly in the link) If this were a Brecht and Wiell song from say The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, we’d read these lines and expect Modernist irony. What do I expect? That Powell had a brain and a viewpoint and meant what he wrote.

CORRECTION: The “Killin Jive” song was actually performed in another Black-audience-targeting picture called The Duke is Tops. They did appear in Two Gun Man from Harlem too, I just trusted my memory more than double-checking my notes,

“All Star Negro Cast” in the film from which “Killin’ Jive” appears

.

In real life and not in front of Hollywood backlot cameras? I can’t say for sure what kind of places the Cats and the Fiddle played in, but as working musicians the places they performed in would surely be physical contexts in a segregated society. Los Angeles had its own Black musical scene and audience around the Central Avenue neighborhood, and they could have played there. In a following post in the series we’ll get into what I can figure out regarding their musical career and travels from supposition, elements in the scrapbook, and some new information I was able to gather this month. More to come here soon in this series.

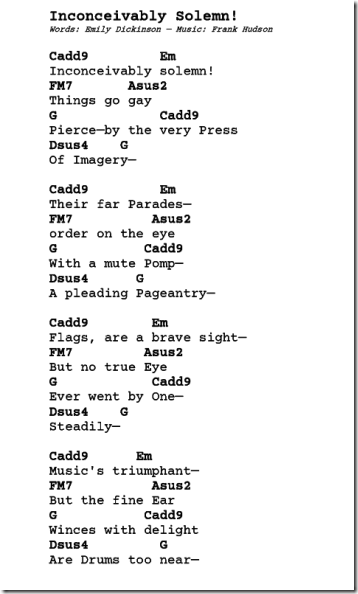

For a musical note, here’s a Langston Hughes poem remembering time on the other side of the tracks. There should be an audio player gadget below, but if it’s been red-lined out for you, this highlighted link will open a new tab with its own audio player.

.

*Radio was more-or-less the streaming of my era, but it had the extra dimensions that you knew that others were listening to the same music you were listening to at the same time. When “your record,” the one you made, or simply the one you cared about as a listener, was played on the radio, you may have been alone in your room or your car, but you knew also you were one of some many in a simultaneous nexus. Music on television or in the movie house was most often a generation behind. I’m nowhere near a Jazz musician in skills, but I owe it to TV and movies of my youth that when I hear a Jazz take on a “Standard” I usually know the tune.