Valentine’s Day comes within Black History Month in the United States. Might be coincidence – but when it comes to diverse lyrical depictions of love, desire, heartbreak, and joy-in-connection depicted in song, this would seem appropriate. But this wasn’t always so.

Read on. We’re going to talk about poetry and flowers – well, sort of, and there’s some nasty bottleneck slide guitar at the end of this.

Choosing the poetry of Claude McKay as my Black History Month focus this year, I’d have to deal with some preconceptions of his work. One, his poetry is written in the 19th century style that the Modernist poets I often select for use were all about replacing. I admire that early Modernist outlook, but it’s not required if the older prosody and what it is conveying attracts me. A second factor is that McKay (like many poets that don’t reach the upper levels of The Canon) is only known for one or two poems – poems anthologized enough to be recognized, but also poems misrecognizing the range of his poetry. Another Afro-American example I’ve featured here is Chicago poet Fenton Johnson who is known almost entirely for one poem, the short, bleak, despairing “Tired” that begins “I am tired of building up somebody else’s civilization.” McKay’s equivalent is the defiant sonnet of self-defense “If we must die…” which is a striking, memorable, work – and then there’s one other poem of McKay’s that retains some current readership, his complex and eloquent poem “America.” Despite these old-school accentual syllabic rhyming verse structures and elevated literary language, either of those McKay poems could be read today, in this America, and be understood as vigorous statements about contemporary civic issues – so perhaps there’s nothing wrong with those two being McKay’s representation. They’re not valentines though.

But.

Reading through McKay’s 1922 Harlem Shadows collection and his other 1920s work, I’m struck by how much of his poetry deals with his immigrant status – and then even more: how many are love poems or poems dealing with desire and eros. In the short term, this cost McKay. Long time readers here, or those familiar with American Black history in this era, may remember that the Afro-American cultural and political leadership circa 1920 were all about establishing the sober respectability of Black Americans, and erotic expression was not part of that. This wasn’t just run-of-the-mill prudishness – after all, rape was part of the crimes committed against Black Americans, and also a criminal fear used to trump up racism and violence against Black men. In either case, and beyond abuse, sexuality could be too easily seen as an “animal nature” thing not befitting a safe civic personhood.

So if we take Langston Hughes’ The Weary Blues poetry collection published four years after McKay’s Harlem Shadows you’ll see some documentary depictions of nightlife depicted journalistically, and praise for disreputable Jazz music then associated with “loose living” – subjects that were considered edgy enough for The New Negro gatekeepers then – but you won’t see Hughes including a bunch of poems about erotic love.* Harlem Renaissance predecessor Paul Lawrence Dunbar wrote some sentimental love poetry which just might have some subtext,** but it was without the heat of desire. McKay, on the other hand, filled his 1922 book with it.

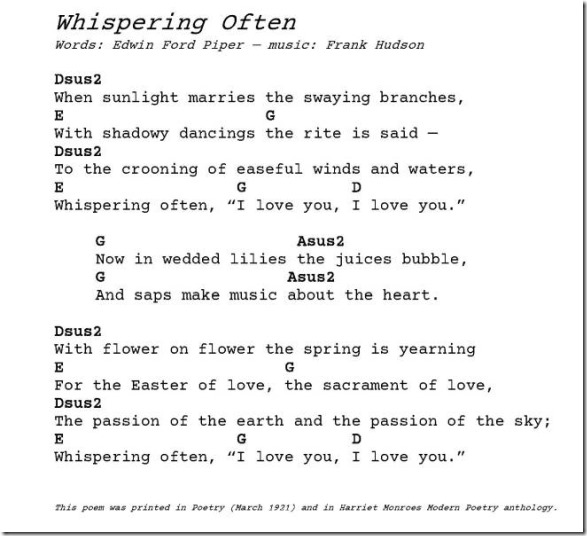

If he got away with it at all, it was because McKay hid his eros in poetry like that in today’s poem/now song with a hot-house language of flowers and landscapes cloaking the heavy-breathing. I had trouble when labeling my Apple podcasts posting of this song today. Should I click the warning “explicit” or stay with my usual “clean?” Do I have, as my own city’s bard once proclaimed, “A Dirty Mind” to think that this poem is written knowing that flowers are a plant’s sexual organs?*** In the end, I clicked clean, not because the poem isn’t saturated with desire, but because one must read it as a double-entendre to see that. My hope is that any kids that might find it (or its text I’ll link here) will gain research skills of some value, and I won’t go through the lines of the poem and “translate” what I think is being depicted – that’s the last thing kids want to hear an old man speaking of. IYKYK.

One other thing is striking about today’s poem, and much of McKay’s poetry of love and desire: there’s no gender in it. Accounts and accepted evidence vary somewhat, but many who want to determine McKay’s own biographical sexuality think he was bisexual. Given that his poem seems to be set in a diverse flower garden, it might resonate with a variety of ardent lovers as we approach Valentine’s Day.

When I tried to type Blake’s “lust of the goat” into a search engine to check the exact wording, I typed something that autocorrected “lust” to “load.” To my amazement AI decided to explicate goat loads of meaning from that typo.

.

Music? One DEI I can’t foreswear is whatever I find myself doing musically, I’ll want to try something else if I see I’m settling into a pattern. So, back into the cases go the acoustic guitars. No spare pianos either. Glass bottleneck on the finger, Telecaster plugged in, and grindstone to the amplifier gain. The lust of the grit is the bounty of God! You can hear that with the audio player below. What, no player gadget? Joys impregnate! Sorrows bring forth! Clicking on this highlighted link will open a new tab with its own audio player!

.

*This Langston Hughes poem that I’ve performed is read as a depiction of the man’s own personal eroticism by many readers. I’m not entirely sure of that.

**I still not sure if this Paul Laurence Dunbar Valentine poem intentionally means to invoke slavery – it would be a stranger and stronger poem if it does.

***McKay came to America to go to an agricultural college, horticultural birds and bees would be a given. Flowers are often represented in his poetry, as much as in gardener-poet Emily Dickinson’s verse.