Do you think you know Robert Frost? You know: steadfast New England farmers, Currier and Ives snowfalls, happy roads less traveled by. We might think of Frost as the friendly Modernist, with good ol’rhymes and rhythms and narratives of American scenes of Americans bearing up to the burdens of life.

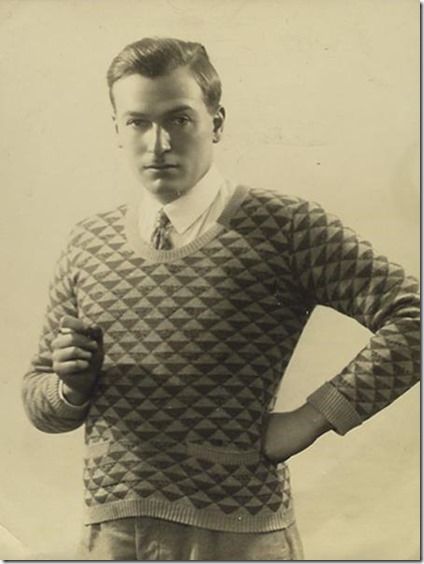

Robert Frost. Wry poet of the good old days—or maybe not?

Today’s piece is instead the hard-boiled Robert Frost. It’s blank verse, but the beat is implied, the sentence structures beat against it, and my performance choice was to not emphasize the meter. What “The Vanishing Red” portrays is, straight up, a racially-motivated murder, and the way Frost tells the tale uses sly ways to frame this story.

He doesn’t get out of the first line before he starts this framing. One of our characters is called the “Red Man” by history. A term roughly equivalent to the N-word for indigenous Americans, but one that in Frost’s time was not considered socially unacceptable.* Frost wasn’t going to shock or disgust his readers in 1916 with that epithet at the start of his poem, like he might some today, but he wants us to know from the start that the race and history of this man is material to what is going to happen—but we don’t meet him yet.

Instead we meet another man, the Miller, who’s talking in a way we might find familiar. He starts out by telling us he’s not guilty of something before he’s even been charged with it, claims too that he’s not one of that PC brigade who “talks round the barn” instead of straight talk, that he’s a get-it-done doer.

Frost adds just a tiny bit of narration after the Miller’s speech. Some may read this narration as excusing the man, but the narrator’s pointing us to think about two things as the story will continue. The narrator says, let’s not consider this as history (“too long a story”) or politics (“who began it”). As we’ll soon see, we’re going to consider this as an Imagist poet would consider it, as a presentation of what Ezra Pound called “an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time.” History can be dulled by time. Politics says there are two sides.

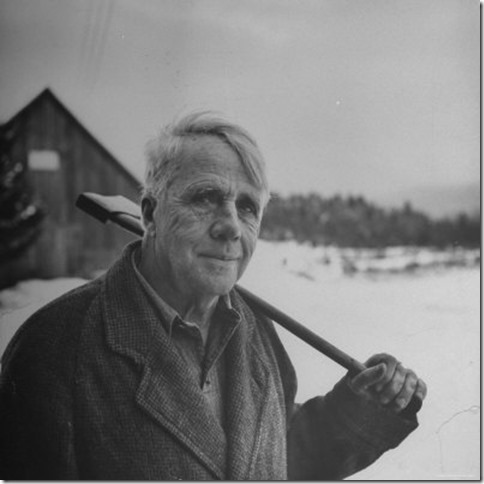

Nostalgic postcard or dark satanic mills? Frost reports, you decide.

But first we have one more exchange of dialog. Our unnamed “Red Man” is at the Miller’s mill, and we hear nothing he says directly, but we do hear what the Miller puzzles about what the other man is communicating. The Miller portrays the other man as without English words, but he interprets some “guttural exclamation” anyway as surprise, and this is somewhat sketchy. Is the native American puzzled by the mill’s mechanism? Surprised at being seen by the Miller?

Is the Miller even reading the other man well? I think not. Afterall, the Miller has another reaction, stronger than his sense of what the other man may be feeling, and Frost’s narrator also doesn’t “talk around the barn:” it’s disgust. But that’s not what our Miller portrays in his next piece of dialog. He acts friendly, offers to show “John” his mill.** Ah, the “Red Man” has a name, he’s not some reductionist cypher for an entire continent’s indigenous peoples, and since it’s an English name, we might surmise that he might even be one of the Massachusetts tribes that attempted to synthesize with the new rulers, taking to Christianity and living in “praying towns.”

And now the Imagist poem begins, ten lines. The Miller opens a trap door and shows John the water-power wheel, and a poem that has been entirely without imagery suddenly gets a vivid image. The wheel’s water forebodingly is like struggling, thrashing fish. The door closes, and the door’s handle (a metal ring) we are told makes enough noise with this shutting to be heard above the noise of the mill. And the Miller returns upstairs, alone. The wheel’s turned around to the beginning of the story where the Miller laughs, though it’s not quite a laugh. He meets a customer carrying more meal to be ground at the mill, who doesn’t understand what has just happened. We ourselves are just understanding what has happened.

What has happened? The racist Miller has thrown John, the “Red Man” into the mechanism and killed him. Frost wants you to feel that by showing you this moment in time, but he also wants you to vividly feel the lack of notice, the vanishing in the title, which isn’t some passive mystery, it’s an act of human cruelty.

Today’s music is two pianos, bass and drums. I’ve been suffering from a cold for the past few days which made completing today’s spoken word component a challenge, and I did miss one phrase in Frost’s text and didn’t get another one completely correct, but you didn’t get to hear any of the coughs and voice cracks from the bad tracks either. To hear “The Vanishing Red” use the player below.

*For example, the college I went to over 50 years ago called its sports teams the Redmen then. I had a tiny part in the beginning of the process to change that.

**Acton Massachusetts had a grist mill and more. I can’t find any pictures of them, but the town still has a Grist Mill Road.