Last time, American satirist Mark Twain took aim at the pretensions of half-hearted sentimental memorial verse. Today’s barbs for bards are from a younger Twain. The text is taken from what was apparently a journal entry written on shipboard in 1866, before Twain was established in his literary career. Elsewhere on the web “Genius” is identified as a poem, and perhaps in manuscript that intent is clear—but when I first read it, I suspected it could be notes for something not yet finished, or even cue-phrases for a humorous lecture.

150 years and the mystery of what it is hardly obscure the points Twain makes. The alienated, self-pitying, and intoxicated artist, damaged by a feeble market that is itself a claim to their originality, is a type we can still recognize—even for some of us, in the mirror. In my performance I chose to bring forward what I think is some ambiguity in the piece. Twain never quite shows the work itself is a worthless affectation, while indicting the affectations around the artist specifically and wholeheartedly. Yes, the poet’s rhymes are said to be “sickly” and “incomprehensible,” heavy charges laid on them by those “with sense” who are not hip enough to appreciate the “genius.” Every single poète maudit* since would take those charges as badges of honor. I sense some mixed admiration for this stubborn guy who sensibly should take available steady work as a sawyer, but instead sticks to writing.

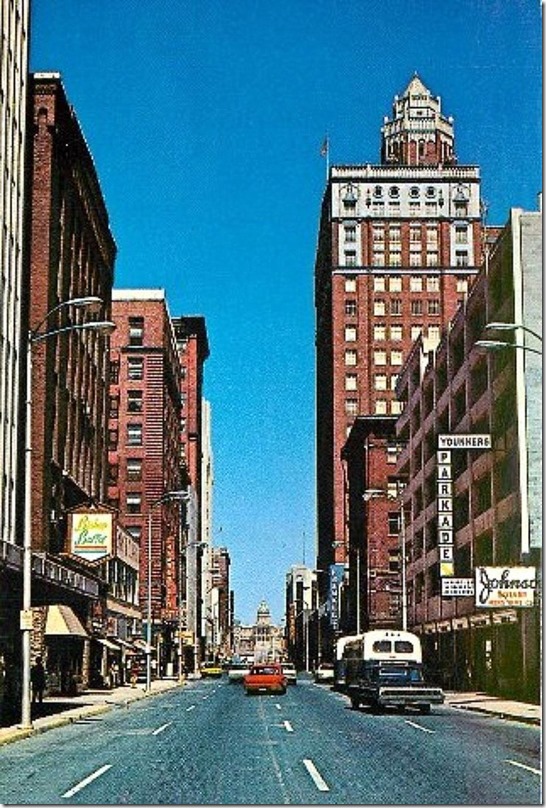

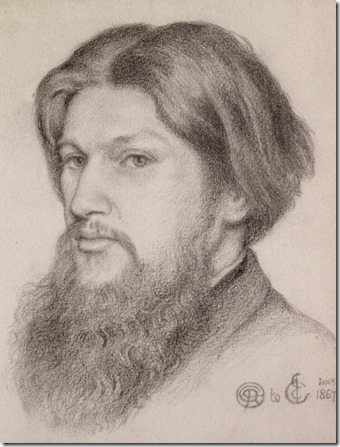

The pen name was still fairly new, and the ‘stache hadn’t yet leapt to his upper lip, but here’s the twenty-something Twain.

After all, Twain himself was not far from that state. He was not yet a successful writer. He hung out with a group of self-described Bohemians in San Francisco. He lived in his Twenties a fairly reckless and feckless life, fleeing to the west from Missouri to escape the Civil War and the draft, fleeing Virginia City for San Francisco to escape a duel occasioned by a slanderous article he had published, and this particular journal entry had him on a ship heading to Hawaii, leaving San Francisco. “No direction home, like a complete unknown…”

And all his life, Twain was two, a man who clearly wanted success and recognition, but whose writing and outlook was distrustful of established norms, propriety, and shibboleths.

If “Genius” is notes for a talk and not an intended page-piece, it points out that Twain’s eventual career included substantial work as a speaker who told humorous stories. We have a name for that sort of work today: stand-up comedian. During his time out west Twain met and befriended Artemus Ward, a man who has since been called the first stand-up comedian. They met in the mining boomtown of Virginia City, and the story goes that after Ward’s performance, Twain took Ward on a drunken tour of the rooftops of the town. Given their state, the risk to American culture of such an intoxicated lark was in retrospect considerable, so perhaps we should thank the town constable who along with a shotgun filled with rock-salt, ended that escapade.

So, Twain lived to write his books and to skewer poetry. The player gadget to hear my performance of Mark Twain’s “Genius” (whatever it is, or was intended to be) is below. Here’s the full text of “Genius” as is appears elsewhere on the web.

*Was Twain skewering a particular poet, or a type? Edgar Allen Poe, the American poet of his time who lived and sang the “songs of a poet who died in an alley” would be one candidate. And it could be in some part a reflection of persons in the West Coast bohemian scene he was sailing from.