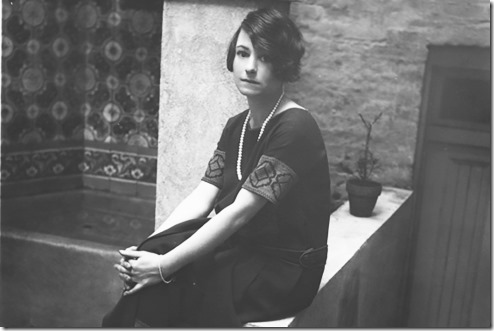

Is Dorothy Parker a humorist or a poet? If choosing one, do we diminish the other? Wikipedia leads with the latter – which surprises me a little, because if you’d asked me in the midst of my literary engagements decades ago, I’d have replied the former. The poetic literary cannon doesn’t mind wit, but it downrates those suspected of making humor the main point of their work. And there’s the matter of how it was presented: Parker published in general periodicals (though at a time when they were still engaged more than now with literary poetry). Her collections are filled with short verses sharply focused on catching the busy glossy page-turner a century ago. Are they the poetry equivalent of a New Yorker cartoon – some insidery cultural memeability, yes – but not meant to be judged alongside fine art with substantial complexity?

What if we were to read her in translation, and she was a writer from a culture and times we were substantially distanced from? Imagine a poem like the one I’ll perform today not as a 1920’s American work by a writer whose lifetime overlapped my own, but as a fragment of Sappho or a poem taken from the pen-work of Li Po? Might we see something else?*

Here are some things I see looking at today’s poem this way as I worked to set it to music and perform it. The first is some awkward syntax, some of which could be “poetese,” that mangling of normal word order that is reaching for a sense that this is “special” speech cast in some archaic or fancified manner. In humorous verse this is often used as part of the joke: you were expecting some grand edifice of beauty and truth – dressed in this artificial, inflated manner – and instead you get a pratfall? Ha ha! This still works as a humor tactic, though its sharpness is dulled by the relative absence of literary poetry in our culture. Needing to reach the rhyme is part of the humorous charm of light verse – forced or outlandish rhymes are laugh points. Parker doesn’t go Ogden-Nash-hard on this here, but I smiled when the “rankles” and “ankles” chime goes off in the first verse.

An allied tactic is the use of some unusual words, another high-falutin stance that aims to make the pratfall funnier. I actually had to fix my recording of this. Having recently worked on Yeats famous apocalypse “The Second Coming,” I actually sang “And gyre my wrists and ankles.” “Gyve” is to bind or tie, “gyre” is to move in a circle or spiral. I don’t know, maybe I was visualizing RFK Jr’s falcons besetting the poem’s speaker with fetters in their beaks and claws.**

Here’s a chord sheet for the song I made of Parker’s poem

.

Also noted when dealing with this poem: the situation set out in the poem is extreme, and taken literally it’s a portrait of bondage, exile, or imprisonment. If parts of this survived as a Sappho fragment, I can see this being decoded erotically. Scholarship and kink cross-over more often these days – and the poem’s imagery is specifically sensual – but don’t put that in your scholarly paper until you do further research.

And here’s the last, most important thing I noticed: I’ve been living this poem recently. First off, a sidelight on the manner in which I found Parker’s poem: I have been going through books and disposing of most of them. My wife is distressed by the number of books and recordings I’ve accumulated over my life. Little difference most sit shelved at the edges of rooms, they are clutter, and she believes that the space could be used otherwise. At this point in my life, I can see this issue another way: I’m of an age that there’s no world enough and time to imagine going back and rereading or reading the majority of them. Books that I once treasured as reference materials are likely obsoleted by the Internet. For example, I’m torn about keeping my thick hardbound French to English dictionary which was a companion when I started translating French poetry years ago. I’m keeping most of my books of poetry, and some on music, as I intend to keep doing this Project. Novels and general non-fiction? To be carried away.*** Is it clutter? Among my small segment of humanity, I’m not alone in being comforted by books and music surrounding me, and the irrationality of there being more than I can consume in whatever time I have left as an aged person doesn’t change this, but having accumulated an overwhelming amount submerges some books. Going through my books I was surprised to find a 1930’s printing of Parker’s collected poems. I don’t remember buying it, though I did spend time and a dollar or two in any used bookstore that had a hardbound poetry section during my youth.

Last week I read through the first segment of Parker’s book, work that is now in the public domain, and it’s there I found “Portrait of the Artist.” I’ve mentioned recently that my opportunities to create new work here has become constrained. I’ll spare you the logistical details, but in the early years of this Project I had the five workdays of the workweek to research, compose, and record. The hundreds of pieces I produced in the first half of the Parlando Project’s run say I used that time productively – but if I was to be honest, I’d report that there were days I just blew off, knowing that the next day would be just as good to start or complete some Parlando work.

Now? I can’t tell for certain when I can record, I just know there will be fewer hours available. My energy level as I age is lower, and my old body no longer finds itself able to sit in an upright office chair for hours at a time. I do more of my research and reading on a tablet, which however marvelous, is a poorer environment for complex work with its constrained single smaller screen. I’m still able to play my instruments when I can use my studio space, though I need more time there practicing or simply blowing off the stress of life with a plugged-in electric guitar moving air around me. There are some mornings when my wife, being helpful, will tell me I’ll be able to work on recording for a few hours that day. I’ll think: I don’t have any new poem-texts selected, or the basis of a musical setting ready to be realized, and my energy is low. What can I do (anything?) with that time? And if I can’t do anything, when will the next chance come?

Whine. Whine. What else is the Internet for – complaint and its opposite, the carefully curated presentation of one’s perfectly actualized life to be envied. In Apollonian distance I can clearly see that to have the opportunity and the wonderous technology to do creative work, is a historical exception of the first order.

But then artists, many of whom are toward the introverted side, are often like the one in Parker’s poem: always swearing they wish they had the solitude and freedom from the distractions of life. And then the poet faces the blank page, the composer the silence in the room, their muse taunts them “What’ya got?” and the artist mumbles “That’s your job,” knowing that there’s really no one else in the room, just as they wanted.

There are lots of things in life that are temptations for self-pity or abuse. Sometimes the de profundis answer is “Ha ha.” That doesn’t mean it isn’t serious. The consequences for this troubled encounter with the chance to be creative, and perhaps to come up dry, have killed and crippled.

Simeon the Stylite has figured out how to get some work done without Robert Benchley, FPA, George S. Kaufman, Alexander Woollcott, et al.

.

All this feeds into the choices I made in the musical performance of Parker’s poem. I treated it no differently than I would have a “serious” literary poem by Parker’s contemporaries Elinor Wylie or Sara Teasdale, though I believe there are a couple of times I’m subtly winking as the singer seeks the situation of a desert-steeple mendicant. The fool is funny – still is when the situation is serious. This is often the lonely place of business for creativity: weighted on commercial and logical scales, it’s absurd that we do it – even, or especially, alone in that room with silences and tabla rasa.

You can hear this performance of Dorothy Parker’s “Portrait of the Artist” with the audio player gadget below. What, is any such gadget gyved up somewhere? Well then, I provide this highlighted link that will open a new tab with its own audio player.

.

*We can prosecute mootings on more recent American authors too. I’ve recently written here on the difficulties in deciding how often Emily Dickinson means to make a humorous/satiric point in her poems vs. how often she’s an earnest transported romantic. A mixture? Likely, but what are the proportions? What are we missing if we miss the joke?

**Ah, the powers of overdubbing. I fixed that word-mistake ex-post-facto.

***I’m fond of the term “Death Cleaning” for this process. Time’s winged chariot is heading for Goodwill. While I’m blessed to be healthy for my age, I can no longer fool myself into thinking that someday I’ll get around to this, and that…and that, and that.