The year 2018 marches on, as we pass onward past Thanksgiving toward December. I’m quite thankful for the opportunity to continue this project. Time-consuming though it is to do these pieces, it also continues to fascinate me and (one hopes) it also continues to surprise and entertain you. For me there’s considerable enjoyment in trying out or finding out something new, thinking about something, or playing something, different.

Another blog that gives me those pleasures is My Year in 1918, where its author has been immersing herself in the publications of that epochal year. Her recent thankfulness post looked at some 1918-era people she has run into on that nearly year-long project. As Thomas Hardy put it in his poem of this era, it was a time of the breaking of nations, but as Mary Grace McGeehan looks over her year of 1918, she highlights a few that were mending and mitigating.

Though they may no longer be as well-known, some of McGeehan’s list you and I might recognize: W. E. B. Du Bois, Jane Adams. Others, such as women’s suffrage activist Anna Kelton Wiley and bra designer Mary Phelps Jacob were unknown to me. Three writers get a nod, all three wrote poetry: Amy Lowell, William Carlos Williams and Dorothy Parker.

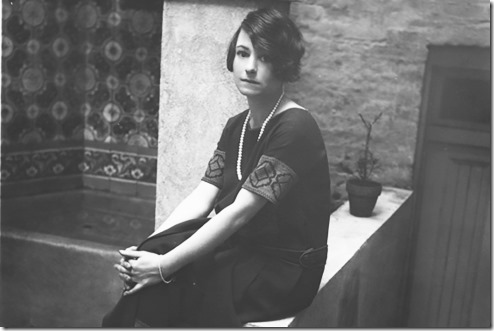

That plant looks like it could use a little water. Dorothy Parker at home in 1924.

Amy Lowell is a literary force I need to address sometime in my own project, though I’ve yet to absorb anything of her poetry. Though I overlooked Williams in my youth, he’s grown on me throughout this project as his public domain, pre-1923, work explores the lyric impulse with eyes whose perspective has been expanded by the Modernist explosion. The third, Parker, is a double surprise. I can see where My Year in 1918’s McGeehan will encounter her, as Parker was writing for magazines (one of My Year in 1918’s chief sources of material), but she’s not some inescapable pantheon writer. And though later in life she became a committed social activist, particularly in regard to African-American civil rights, her WWI self had yet to develop in this regard. But she’s a, a—oh, the never-immortal shame, the art that dare not speak its name—a humorist.

Parker with the Algonquin Round Table group of wits. We don’t know if they’re having lunch with those drinks, but it’s something of a sausage fest anyway. I haven’t seen a caption naming those present, proof that humorists don’t make the pantheon. Besides Parker on the lower right, I think it’s Alexander Woollcott 2nd from left in the upper row, but I’m drawing a blank on the rest.

Humorists, whatever their skill and craft, tend to damage their reputations as literary figures. We like our literary titans dour and serious for the most part. They can scatter a little wit around for decoration or as weaponry, but to be celebrated for their merit—even if that’s all we end up really noting about them, their worthy merit—you need to rise above that. The assumption seems to be: if the point is to make you laugh, the point is ephemeral.

We think too little of humorists as agents of social change, or as participants in the Modernist artistic revolution of the early 20th Century. We do this even after Dada, even after Mark Twain’s now-recognized status as another American who broke Modernist ground before the 20th century.

To take Dorothy Parker seriously (not solemnly) you need to start by acknowledging that she’s fighting with two hands tied behind her back: she’s a woman before women were considered capable of human complexity, and she wants you to laugh at our folly. Parker survives at times wielding dark, survivors’ humor, the sensibility that remembers her poem “Resumé,” a meme in verse about suicide. She might step on a few toes while doing that, and she’ll laugh about it.

Alternate voice here, Dave Moore, has appreciated Dorothy Parker for some time. Several years back the LYL Band covered Alan Moore’s “Me and Dorothy Parker,” and here today is the LYL Band doing a Dave Moore original that expands on Parker’s observations on suicide in his own words.

Parker ended “Resumé” with the punch-line “You might as well live.” I’d add, you might as well create art. After all, even in the worst-case, you’re only burning part of your life-time while struggling with joy and it’s opposite. If there’s no hope, you might as well hope.

Thanks again for reading and listening. Thanks to spreading the word about the Parlando Project. In the Internet world of millions of likes and shares, we’re a small thing, but I’m grateful for you helping keep this little thing going. The player for the LYL Band’s performance of Dave Moore’s “Looking for a Way to Go” is below.

Thanks so much, Frank! This was posted on my birthday and I can’t think of a better present.

LikeLike

It good you liked it, as I forgot to get a gift receipt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found a caption for the Round Table photo in the NY TImes archive through a Google Images search: ROUND TABLERS Fritz Foord, Wolcott Gibbs, Frank Case and Dorothy Parker, seated, and Alan Campbell, St. Clair McKelway, Russell Maloney and James Thurber, standing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aha, and much thanks! The pedant in me loves finding out who those people were. The “Algonquin Round Table” was never a formal organization, but most of these qualify inside it’s circumference.

Front row:

Foord was cropped out of the version of the photo I used, but he was an Art Director at Paramount Pictures.

Gibbs was a humorist who wrote for the New Yorker. Wikipedia says he gets confused with Alexander Woollcott sometimes. Woollcott confusion is apparently a thing, which I have contracted as well.

Case? Well he owned and ran the Algonquin Hotel, so ex officio, a member

Parker. Herself.

Back row:

Campbell. Married Parker and wrote screenplays with her. Their biggest success: the 1937 Frederick March, Janet Gaynor version of “A Star is Born.”

McKelway. Journalist who eventually wrote for the New Yorker. His specialty was crime stories, but I still maintain he could have gotten additional work as an Alexander Woollcott impersonator, as he shares Woollcott’s round glasses and mustache.

Maloney. Another New Yorker writer, where he reviewed the Wizard of Oz as a movie showing “no trace of imagination, good taste, or ingenuity,” but he was also apparently an ace gag writer for New Yorker cartoons in the 30s. He died young at 38. Coroner’s report did not mention embarrassment over the Oz review as a cause.

James Thurber. New Yorker writer too. Better known than any of the rest outside of Parker I’d say.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on My Year in 1918 and commented:

One of the best things about My Year in 1918 has been the people I’ve met along the way. One of my favorites is Frank Hudson, who reflects on poets and writers, many of them from the 1918 era, and sets their work to music. In this post, he mentions the synergy between our projects and writes about Dorothy Parker, one of my favorite 1918 people.

LikeLike

Only just now catching up with your posts. My favorite two lines from D. Parker: If all the girls at Vassar were laid end to end, I wouldn’t be surprised. And: (upon her doorbell being rung) What fresh hell is this.

I suspect one of the fellows in the photo is Robert Benchley with whom she had a years long torturous affair. He’s known for several things (aside from being one of D’s amours) including, while on assignment for The New Yorker, in Venice, sending a telegram: Streets filled with water. Please advise.

As to Don Marquis: My first two cats were named Archie and Mehitabel.

Lastly: I recently attended a reading my a not very good author held in a new (ish) bookstore) an old building in Chicago. The building once house The Dial Magazine which of courser serialized Ulysses and ran some of Hemingway’s earliest stories and included among its contributors, Sandburg.

Here’s a link to the bookstore: https://www.dialbookshop.com/

LikeLike