In search of words to combine with music here, I sometimes find it necessary to translate from other languages. Poetry translation involves following strange paths.

Here’s the path I followed to present today’s piece, Jules Laforgue’s “My Poor Bagpipes.” Throughout this month I’ve been presenting parts of T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” as part of my celebration of April as National Poetry Month. This causes me to look more at Eliot and where he derived his sense of modern poetry from. Eliot’s own testimony says that a late 19th Century French poet, Jules Laforgue was very important to his own poetics. That’s about all I knew about Laforgue: important to Eliot.

I search and find some Laforgue poems, though only a couple in English translation. Luckily, there’s a site, laforgue.org that has put a great deal of his work online in its original French. I pick out a handful that have interesting titles or first lines and see what rough machine translations will show me.

As I looked at the rough translations I was struck by déjà vu—only in English of course. “Hey, that sounds familiar! I’ve read something like this poem.” In French it was “Poètes a Venir,” and of course it was Walt Whitman’s “Poets to Come.” It appears that Laforgue may have been among the first to translate America’s Whitman to French in 1886, while Whitman was still alive. And from his work translating Whitman, Laforgue began to write “vers libre”—free verse, himself, helping to pioneer that idea in French poetry.

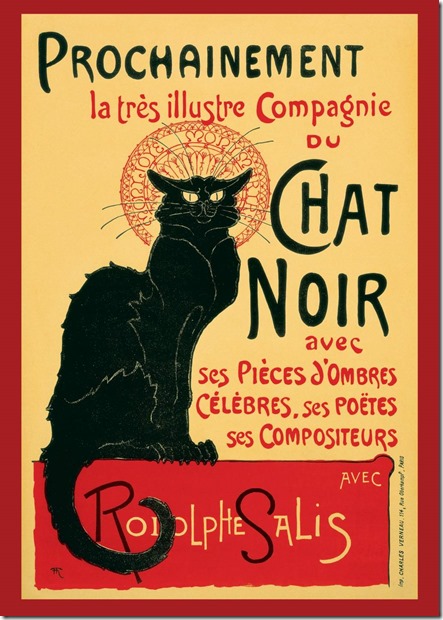

“The very illustrious company of the black cat with his famous shadow plays, his poets his composers.” Remembered by its posters long after it closed, the Chat Noir cabaret was a place where music and poetry mixed in 19th Century Paris. A very Parlando Project thing, no?

I will not be translating Laforgue’s translations of Whitman back to English here. I picked his “Air de Biniou” to try, primarily because I was intrigued by the first line “No, No, my poor bagpipes.” I’m attracted to incongruity and black humor, and I kept double-checking to make sure that line’s “cornemuse” in French must mean “bagpipes.” The poem’s first verse seemed to refer to the bagpipes’ famously raw timbre and pitch issues: “everything is a mistake, everything turns out bad” claims Laforgue’s first stanza.

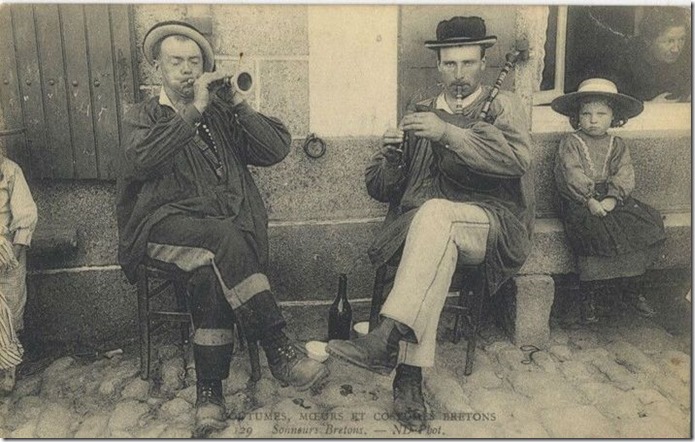

Inserting gratuitous bagpipe joke:

Why do bagpipers walk while they play?

To get away from the sound.

As I worked on it, I had trouble with several words, two or three of which I’m still unsure I’ve translated correctly. This may be a general issue for anyone translating Laforgue, as he liked to play with language and meanings, sometimes using unusual words. But I soon had a more serious issue, after dealing with “occit” in the second stanza. A poet’s images are not his literal manifesto, and irony was part of Laforgue’s stance. In this second stanza he says Nature is a wife the artist will kill. I get his point: the artist thinks they can better the mundaness of nature and create something new and above it. And it’s nature—an inanimate concept, not a person. Yet and all, it’s still a too-casual image of a too-serious and widespread problem, domestic violence, for me to be happy with it. Looks like this is a general issue with Laforgue too. He consistently used images of women, sex and relations with women as a repository for his issues with our biologic nature. In a word: misogyny.

Clearly he’s not alone in this. It could be one of the things Eliot picked up from him too. Like Eliot, he’s not stinting on masculine failures, but this can reveal an attitude that men fail because of their souls while women fail because of their gender. I tried to mitigate that stanza by dealing with another problematic word in it: “carambole.” It’s a word usually used for a particular fruit, but it’s also a bumper pool game, and something like that later meaning I think was what Laforgue intended. I was going to use something like rebound or carom in my translation, but at the time I performed it, I went with a more archaic meaning of the word where it may refer to cannons. At least that put the poet and Nature in a running battle. I may have made a wrong choice there, but that’s one of the things you run into in translation, needing to convey the author’s outlook which may not be your own.

We have little space left to wander more in the twisted paths you find when translating. I think it can be tremendously helpful for poetry composition, because it puts you, hand in hand with another poet, trying to find the right word with the right sound and connotations.

“Je suis bagpiper!” says the man in the center. “Daddy, can we talk about the patriarchy and your intonation issues.” says the girl on the right.

But one last thing, those surreal bagpipes in this French poem. Laforgue’s family was from Breton France. Bretons are a Celtic culture, and yes, they have bagpipes. As to my music here, while I enjoy composing string parts and breaking out the classical guitar, sometimes I don’t want to be careful, I just want to grab electric guitars and bash something out. “Everything is a mistake” says Laforgue. Nonetheless. Use the player below to hear it.

Very interesting post. Have you seen the February 1918 issue of The Little Review? It’s a compilation by Ezra Pound of recent French poems (in French), including several by Laforgue. I also knew about him because of his influence on Eliot, but when I read “Mais voici qu’un beau soir, infortunee a point/Elle meurt!”, “influence” didn’t seem like a strong enough world. The issue is here if you’re interested: http://modjourn.org/render.php?view=mjp_object&id=LittleReviewCollection.

LikeLike

Thanks very much for the link! I read that and even took a look (roughly) at some of the poems. I decided to write just a bit about how Free Verse/Vers Libre went from America to Paris to London (rather than taking a direct flight) in today’s post partly from what your link reminded me of.

LikeLike

I’m glad it took you down an interesting path. It never occurred to me that the French-American influences went in both directions through Whitman. Meanwhile, your discussion of Sara Teasdale got me thinking about how good poems don’t have to be cutting edge. I mentioned it in my most recent post, on poems about mothers.

LikeLike